*The selection of an independent Supreme Court and the reformation and abolition of laws that favor corruption are necessary actions for the International Commission against Impunity to take in Honduras.

**The Xiomara Castro administration has not made any advances in the establishment of an International Commission against Impunity in Honduras. The government’s actions in the fight against corruption are contradictory and face great political challenges.

Expediente Público

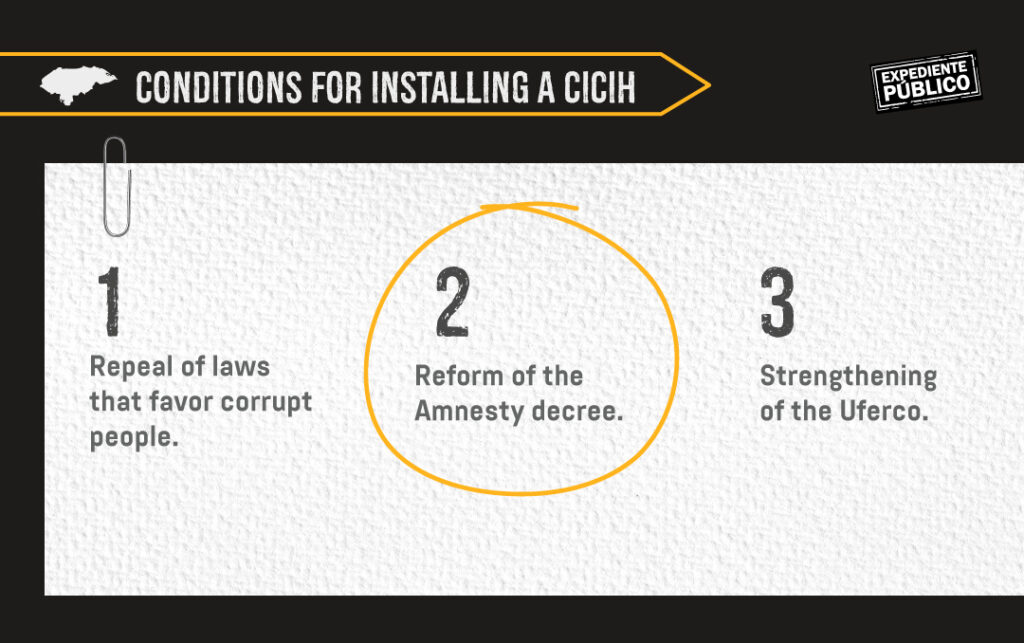

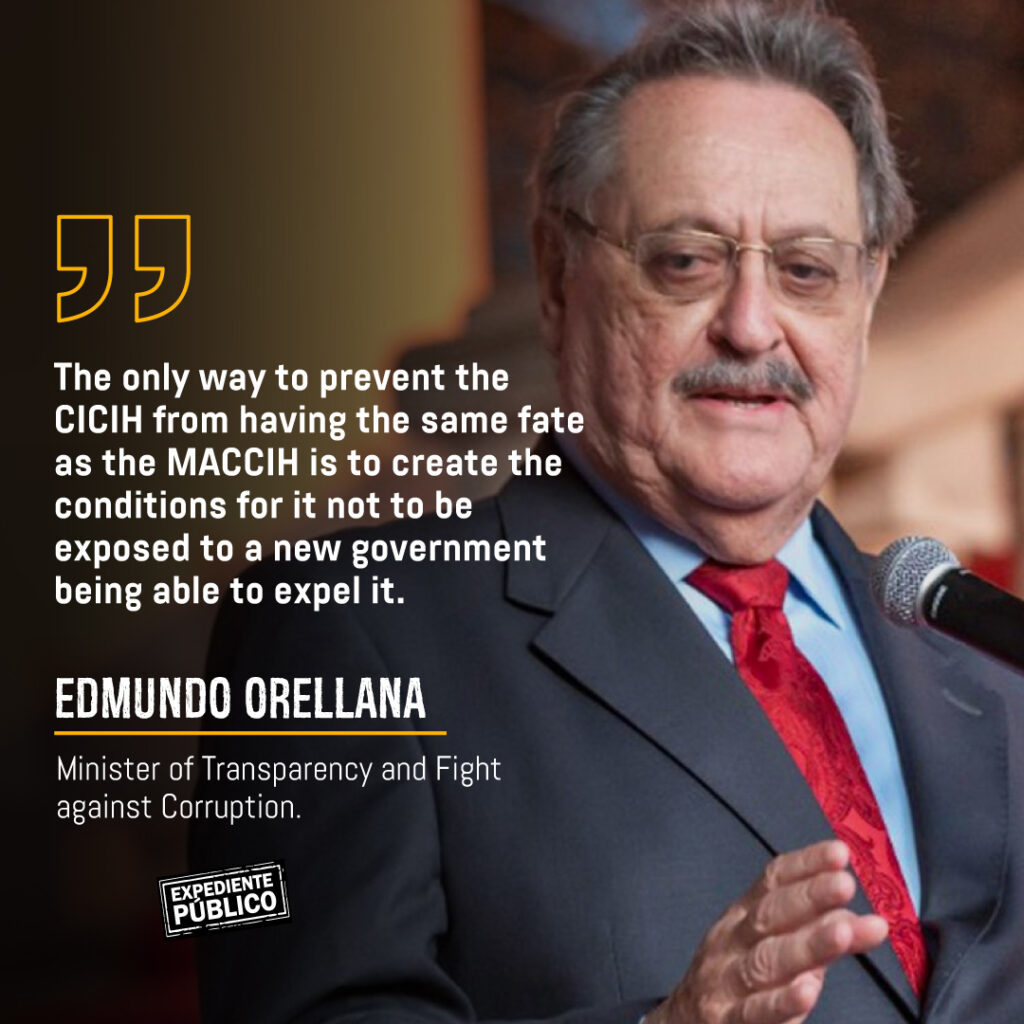

Justice sector reforms, the abolition of laws that protect corrupt actors, and strengthening the Special Prosecution Unit to Combat Networks of Corruption (UFERCO) are conditions that foreign policy analysts abroad and civil society organizations recommend that the government of Xiomara Castro consider before establishing the International Commission against Impunity in Honduras (CICIH). “It is important that not only a prosecutorial unit replaces the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH) but also that such an organism fits within a comprehensive reform of Honduras’ judicial system, which would pave the way for its arrival,” according to the report, “Coalición Anticorrupción, aspira a una CICIH independiente, autónoma y con enfoque de derechos humanos,” published by the Centro de Estudios para la Democracia (CESPAD). The document suggests a series of conditions for the installation of the commission.

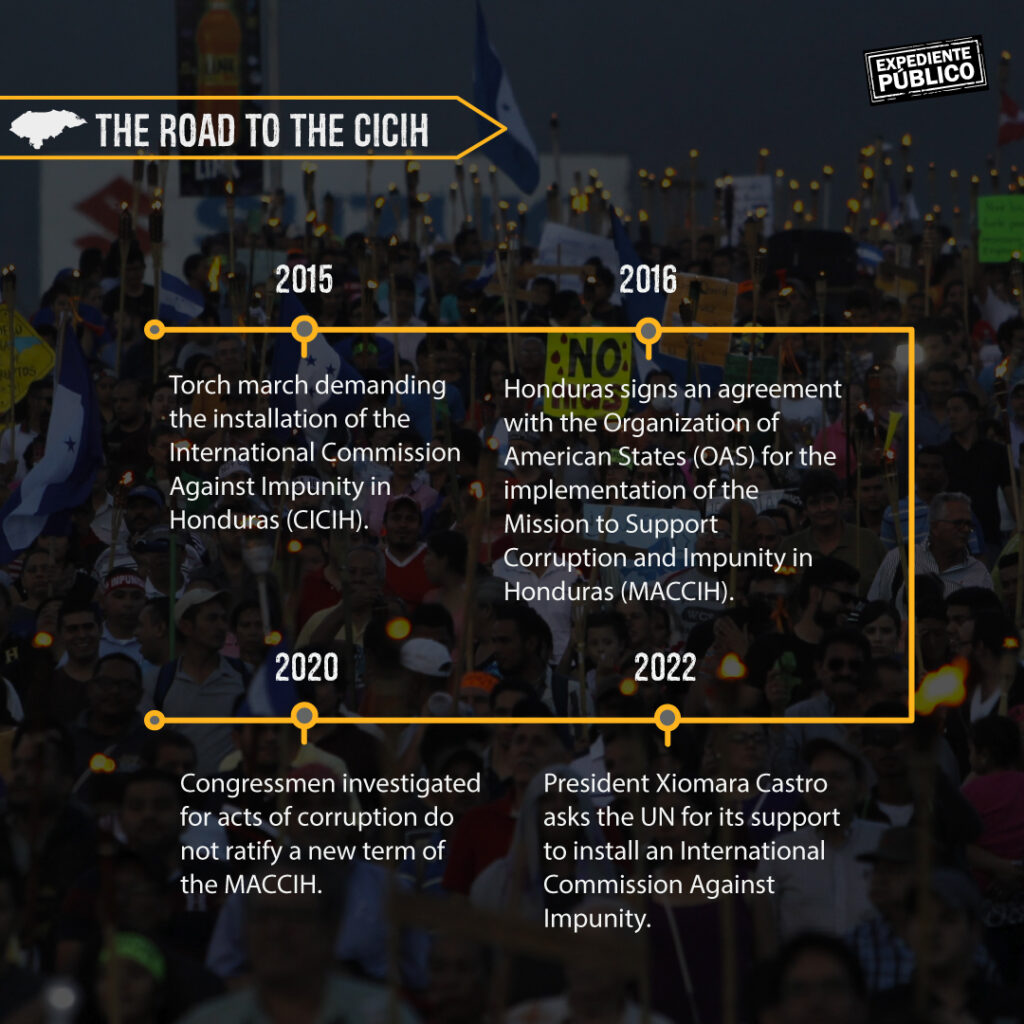

On February 17, 2022, the Ministry of Foreign Relations of Honduras solicited support from the United Nations Secretary General to create the CICIH. On May 10, a mission from the United Nations arrived in Honduras to meet with government officials and representatives of civil society. The mission elaborated a report that will allow the Secretary General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres to decide how to respond to the country’s request. To date, there is nothing new to report, according to Alice Shackelford after receiving a request for information from Expediente Público. The Honduran government awaits further information from the United Nations, but the international organization has not set a specific date to reveal the decision.

Read: Honduras: La lucha contra la corrupción, la gran tarea pendiente de la presidente Castro

Freedom for those accused of corruption

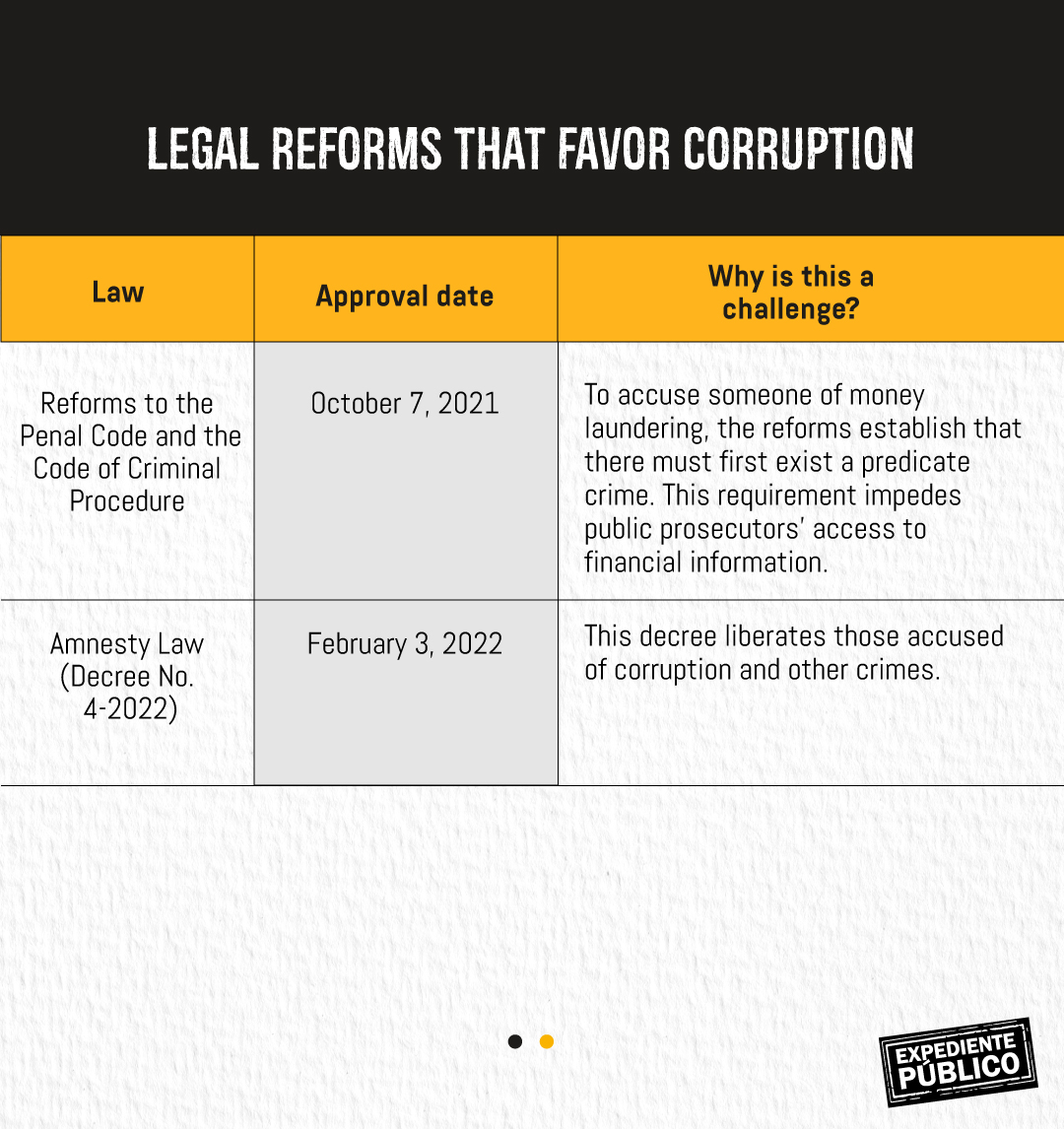

Gustavo Irías, director of CESPAD, considers that the Amnesty Law, which would be an obstacle for the installation of the CICIH, should be revised and reformed by legislators. Amnesty figures in Chapter Two of the “Law for the Reconstruction of the Constitutional Rule of Law and for the Non-Repetition of Events” established by Decree No. 4-2022.

The law grants “general, broad, and unconditional amnesty” to officials, employees, and authorities elected during the administration of former President Manuel Zelaya (January 27, 2006, to June 28, 2009), who is also husband and advisor to President Xiomara Castro.

The decree was approved by Congress on Thursday, February 3, 2022, and published in the Official Gazette of Honduras two days later, a week after Xiomara Castro de Zelaya assumed the presidency.

“There is a need to reform this decree, as there are cases of government officials who have been accused of corruption from the period of 2006 to 2009. While political will to reform the law has lacked due to the coup d’état in 2009, certain actors have avoided the consequences of their actions and the justice system,” Irías said to Expediente Público. Irías adds that “this reform is important to avoid any obstacles to an international commission that would seek to combat corruption.”

The gap between the government and its congressional allies

The approval of this law not only was rejected by the public but also created a rift within the National Congress, particularly between political parties that ultimately allowed for its approval: Salvador de Honduras (PSH), which advocates for reform, and its political ally, the Libre Party, which proposed the amnesty law. PSH Congresswoman Maribel Espinoza told Expediente Público that the law creates an obstacle to justice in releasing people “whose actions do not fit within the definition of a political crime.”

Such is the case of Enrique Flores Lanza, who served as minister of the presidency from January 3, 2008, to June 28, 2009, the day of the coup d’état. The Public Prosecution Service charged him with theft of around 50 million lempiras or two million dollars from the Central Bank of Honduras, falsification of documents, three counts of abuse of authority, and fraud. In other words, the crimes Flores committed were not related to his political participation, but rather, were corrupt acts. Flores lived in exile in Nicaragua for 12 years, until March 18, 2022.

Marcelo Chimirri Castro, a relative of President Castro, also received special treatment. He was sentenced to 17 years in prison (eight for abuse of authority and nine for illicit enrichment).

Read: En Honduras, acusados por corrupción se benefician de amnistía

“The PSH proposed to reform the Amnesty Law so that judges could not apply the law to all who requested amnesty without the proper qualifications required by law,” said Espinoza. PSH representatives Ligia Ramos and Maribel Espinoza introduced a reform bill to Congress that would establish the concept of political crimes and decrease the number of crimes found in the original decree.

The Amnesty Law was approved in such a way that it would benefit those who committed crimes of money laundering, misappropriation of public funds, and embezzlement and theft, among others. If left as is, the law would hinder the work of the CICIH.

However, Libre representatives, such as the vice president of Congress, Rasel Tomé, have publicly affirmed that the reform will not pass.

The CICIH and the Supreme Court

By law, Congress should open the call for candidacies to replace incumbents of the Supreme Court of Justice (CSJ) in July of 2022, and the election process should conclude at the beginning of 2023.

Read: Inicia el debate para que la Corte Suprema en Honduras no siga en manos de políticos

One of the organizations that demands a reform of the election process for Supreme Court magistrates is the Social Articulation for Transparency and Justice (ACTJ), composed of 29 businesses, universities, bodies of the Catholic Church, and other civil society organizations. Their members were clear about their support for the CICIH and the minimum requirements to ensure its ability to function. One of these requirements is the election of a Supreme Court that is independent of the two other government branches, according to attorney Lourdes Mejía of Plataforma Amplía Nacional Liberadora, one of the organizations that makes up the ACTJ.

To date, magistrates have been elected depending on the political party of the government in power. The current Supreme Court is composed of eight nationalists and seven liberals. In 2022, the country entered a new situation because, for the first time, the leftist Libre Party, which is not one of the two main political parties, governed Honduras.

The ACTJ encourages a reform of the Special Law on the Nominating Committee to avoid the election of magistrates based on political party affiliation.

Legal stumbling blocks

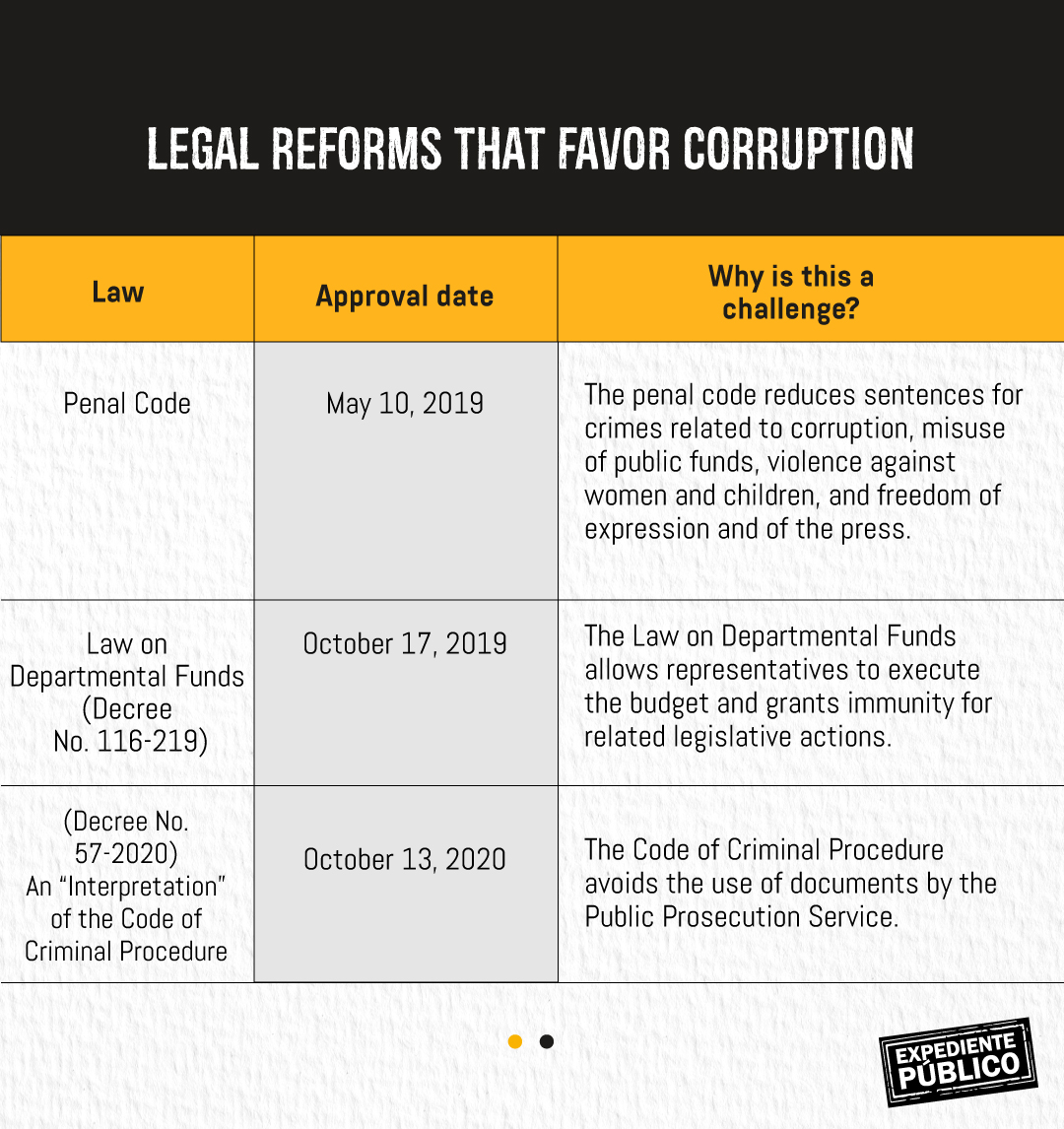

Additionally, there is body of laws that the legislature should reform or eliminate. One of these laws is the “Special Law for the Management, Allocation, and the Settlement of Public Funds” (Decree 116-2019), also known as the “Law on Departmental Funds,” where appropriations are allocated to representatives for management.

Read: La MACCIH, un inconcluso modelo hondureño de combate a la corrupción

Gustavo Irías of CESPAD says that the law has allowed for the management of state funds to fall into the hands not only of legislators but also of public officials, foundations, and nongovernmental organizations. The law also prevents the Public Prosecution Service from carrying out investigations on the misuse of these funds and transfers these functions to the High Court of Auditors, composed of officials who are appointed by Congress for a period of three years.

According to Irías, another law that would inhibit the work of the CICIH is Decree No. 93-2021, which reformed dozens of articles of the Honduran Penal Code and favored those guilty of money laundering, embezzlement, fraud, illicit enrichment, influence peddling, and bribery, among other crimes.

The reform “eliminates some of the predicate offenses necessary for money laundering charges,” says Irías. Before the reform, a person who appeared overnight as the owner of assets and bank accounts could be charged with money laundering to prove the licit origin of his or her wealth. Now, the Public Prosecution Service must first show that the person committed a crime (drug trafficking, misuse of public funds, etc.), through which he or she accumulated wealth, for the government to pursue charges.

The Anti-Corruption Coalition warns that this decree reformed Article 47 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which makes it impossible for prosecutors to obtain, directly, reports from the banking system on personal accounts. Now, prosecutors must ask for authorization from a judge to obtain these documents.

Lastly, according to Irías, Decree No. 57-2020 interprets Articles 217, 219, and 220 of the Code of Criminal Procedure in such a way that seizures and confiscations of documents by the Public Prosecution Service are avoidable. Prior to the reform, the Public Prosecution Service could go to institutions, such as mayors’ offices and ministries, and obtain documents necessary to provide proof of a crime. Now, prosecutors must seek permission from a judge, which can stall the legal process indefinitely and expose the case to significant leaks to parties involved in a judicial system that is extremely politicized.

In light of these obstacles, Luis Javier Santos, head prosecutor of the Special Prosecution Unit to Combat Networks of Corruption (UFERCO) manifested that “Honduras could have 20 CICIHs, but if the country continues to see legal obstacles to the organism, no CICIH will not be able to function effectively.”

“How can we access financial records if there is a decree in place that impedes this work? We must repeal it,” he said.

Read: Pese a la derogación de la Ley de Secretos, la corrupción en Honduras se aferra a viejas artimañas

For representatives of civil society, strengthening the UFERCO is essential to continue to prosecute cases of corruption, as the unit is expected to work closely with the CICIH. The unit must make advances in terms of “budget, qualifications and number of personnel, and logistical capacity,” the director of CESPAD recommends.