*The US government, which helped Honduras with its removal of police officers, does not agree with the current process, whether it says so officially or not, explains Eric Olson, director of policy and strategic initiatives at the Seattle International Foundation.

Expediente Público

Human resource authorities at the Honduran Security Ministry are already beginning the process to reintegrate the ranks of some 2,000 police officers who were part of the 5,319 officers let go by the removal commission between 2016 and 2018. The reinstatement process goes against the opinions of civil society representatives and the US government.

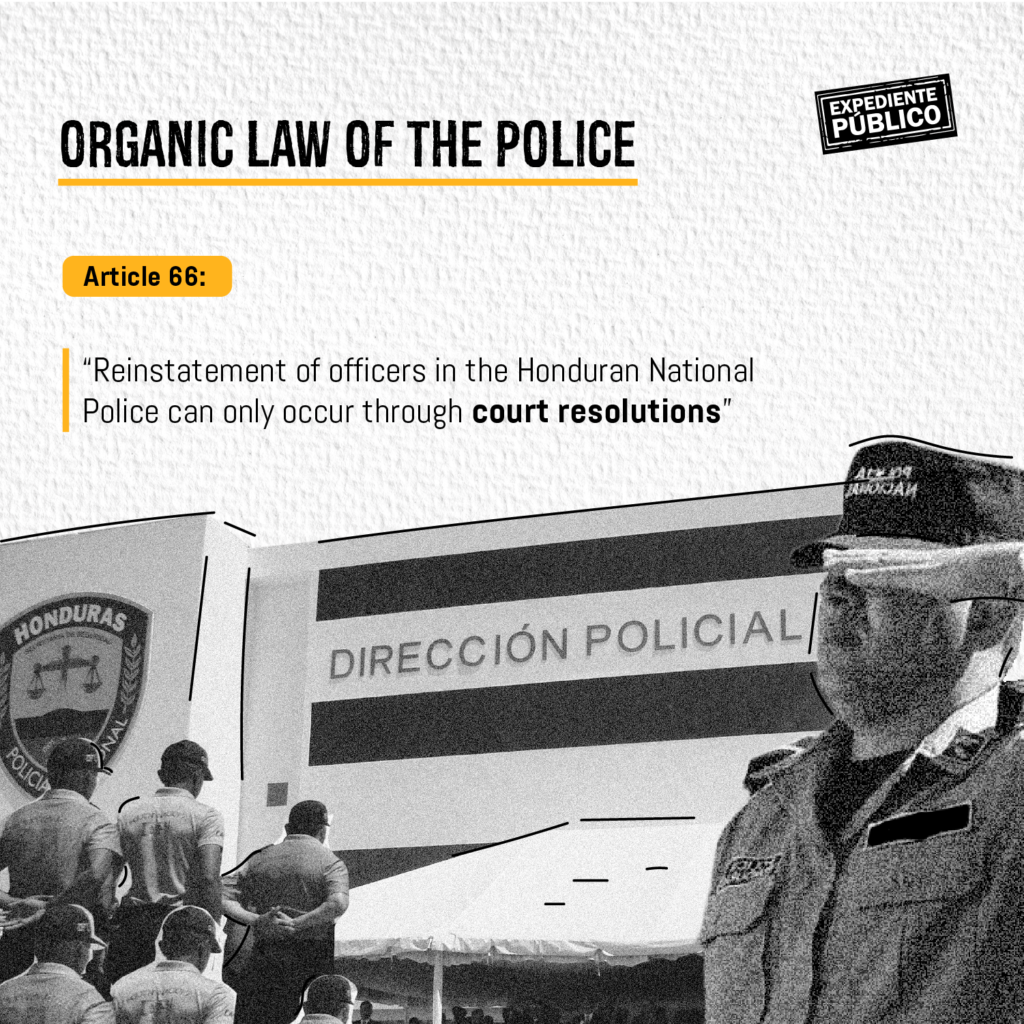

The reinstatement of police officers continues as planned, despite the Organic Law on the Honduran National Police (PNH), which prohibits direct reinstatement by the institution. A variety of actors agree that the layoffs should be permanent, not only for the police force but also throughout all other state agencies.

The reinstatement of police officers

The objective of the director of the Honduran National Police (PNH), Commissioner Gustavo Sánchez is to reinstate 2,700 officers by the end of this year. Of these officers, 2,000 will have joined after having previously been let go by the commission and 700 being inducted by the Technical Institute for Police (ITP) upon graduating in December.

The reinstatement process will also welcome former military officers of the Military Police of Public Order (PMOP). “Remember that, during the last ten years, the armed forces have taken on different functions of the police, which allowed them to gain experience,” confirmed the director of the PNH in an interview with Expediente Público.

According to police, the previously dismissed police officers who are set to be reinstated by the institution will cover 1,800 slots that the National Penitentiary Institute (INP) is required to fulfill. Additionally, they will be sent to new metropolitan units that the PNH has opened across the Central American country.

The process of reinstatement began on May 9, 2022, with the reception of candidates’ documents. Candidates must present a formal application, curriculum vitae, affidavit of assets, criminal record, professional references, proof of vaccination, and proof of medical exams.

To investigate all applicants in a comprehensive manner, the police will ask the Division of Disciplinary Action (DIDADPOL), the National Division of State Intelligence, the Public Prosecution Service, and the Honduran National Audit Office (TSC) for information on each of the applicants. Subsequently, an evaluation committee will conduct polygraph, psychometric, psychological, and toxicology tests.

Lastly, admitted officers will receive a two-month course to catch them up to speed. The institution foresees signing the first contracts, which will be set for a trial period of one year, in September.

In an interview with Expediente Público, Migdonia Ayestas, director of the National Observatory on Violence (ONV), expressed her doubts on the reinstatement of officers: “they need to show that they will not fall subject to the same vices as before.”

“Is it correct to reinstate police officers who were fired by the institution? Those of us who are familiar with the history of the mafias within the Honduran police force know that this proposal is absurd,” warned Óscar Estrada, author of the book, Tierra de Narcos, a study of the evolution of drug trafficking in Honduras.

The risks involved

“Those who were not previously fit to be police officers are still unfit today,” comments Omar Rivera, attorney and former member of the Commission on Refining and Transforming the PNH, to Expediente Público. Rivera adds that the new reinstatement policy is a response to pressures from the police who were laid off by the commission.

In various demonstrations that took place in May 2022, police officers who had been removed from their positions by the commission demanded that Congress repeal Legislative Decree 21-2016, which created the commission, as well as reformed Article 66 of the Organic Law of the PNH, which states that reintegration can only take place through legal resolutions, not through a rehiring process. Expediente Público tried to contact Abel Orellana who legally represents the protestors but did not receive a response.

In addition to its being misguided, Rivera considers the reinstatement of police offers to be illegal, as “they can only rejoin the institution through court resolutions. The article has not changed, so any application received directly by the police is not legally permitted.”

Read: Honduras: incremento de las extorsiones, un negocio criminal que se escapó de las manos del Estado

Eric Olson, director of policy and strategic initiatives at the Seattle International Foundation and fellow at the Wilson Center, explains, in an interview with Expediente Público, that layoffs generally fail because of labor disputes. “I think that the commission was very careful in this sense,” says the expert, who has carried out many studies on police layoffs in different Latin American countries.

The legal precedent that allowed for the reinstatement of police dates to 2001, when the former security minister, Guatama Fonseca fired 30% of the police force but later reincorporated officers into the institution under a Supreme Court (CSJ) order in support of petitioners who claimed that the State had violated their labor rights.

Currently, 85% of those laid off by the commission have submitted a claim on the issue. In the case that the petitioners win their legal claims, the government would have to pay around one million lempiras (41 million dollars) for the wages of 3,900 officers let go from 2016 to 2018.

Even though most of the police officers who were laid off by the institution did not meet the suitability requirements, it is worth mentioning that between 2016 and 2018, the commission sent 1,614 case files to the Public Prosecution Service regarding former police who had committed crimes, which added up to 34% of all layoffs.

However, as of January 2021, only 167 of 1,614 cases were received by the Prosecutor’s Office to prosecute before the CSJ, and only 10% of all cases that the commission presented made it to court. “Many have criticized the commission for not pursuing the prosecution of these cases, but we have to remember that the Public Prosecution Service is the prosecution authority in this country,” says Olson, who considers the weakest point of the layoffs to have been the exclusion of district attorneys and the Public Prosecution Service from the removal process.

And the United States?

Between 2010 and 2013, the US government supported the PNH through donations of 375 million lempiras, annually, or the equivalent of 15 million non-reimbursable dollars. Paradoxically, during this time, the North American government was also the largest donor of the Public Safety Reform Commission (CRSP), which, during the presidency of Porfirio Lobo (2010-2014), was the leading organization for reforms in the judicial and security sectors.

In 2013, after seriously questioning the role of the PNH in extrajudicial killings, such as the murder of the son of former university president, Julieta Castellanos, US Congress suspended donations through the Leahy Law, established by US Senator Patrick Leahy in the 1990s. The law prohibits the allocation of assistance to any foreign army or police force involved in committing human rights atrocities. However, in 2014, the US Congress allocated the funds, once again, to Honduras.

In accordance with the study, The Role of the Commission on Refining and Transforming the Honduran National Police (“El Papel de Comisión Especial de Depuración y Transformación de la Policía de Honduras”), elaborated by the Wilson Center, sources indicated that the removal of police officers in 2016 was only possible after the US conditioned bilateral assistance to the Juan Orlando Hernández government (2014-2022) with an institutional cleanup of the PNH.

Currently, the US government observes the reinstatement of these officers with caution. “Informally, US officials tell me that they are very dissatisfied that after such efforts to clean up the institution, the PNH would reinstate officers. Formally, I have not heard anything. But seeing this setback is a severe blow to the US government,” Olson commented.

Former Commissioner Rivera agrees with the SIF representative. “I have talked with US government officials who have expressed their surprise to me. They are carefully watching how this situation plays out.” However, according to conversations with Expediente Público, the US Embassy in Honduras has not yet published a statement on the matter.

The cleanup job continues

The 2021 murder of young Keyla Martínez in a holding cell belonging to police forces in La Esperanza, Intibucá, some 182 kilometers from the Honduran capital city, meant that police layoffs did not completely get rid of all the “bad applies” in the institution, as former Commissioner Rivera calls them.

“There will always be those who, from one moment to the next, break down and go from good to bad officers. The removal process might have been flawed but can be perfected,” argues Rivera.

For Sánchez, who has a certain openness that is unusual for a director of the Honduran police, organized crime has undoubtedly infiltrated the institution. “We still have officers who are part of pandillas or work for drug trafficking cartels. We cannot deny that.”

The police directorate is committed to strengthening DIDADPOL, the department in charge of internal investigations of misconduct, among officers of the Ministry of Security and police force, ranging from “serious” to “very serious” cases, according to its legal framework. But Sánchez emphasizes the importance of expanding the cleanup of the PNH, in a more permanent way, to all state institutions “involved in investigations and the justice system, more broadly.”

Olson agrees that other state institutions should also go through a reform process. For the security expert, dismissals should be permanent “because corruption continues to reproduce, just as a polluted river accumulates garbage even after cleaning the area.”

The US government’s recent extradition of the former director of the PNH, Juan Carlos “El Tigre” Bonilla is a very current example of how organized crime and drug trafficking have penetrated the institution. Despite his dark legacy, a portrait of Bonilla still hangs in one of the hallways close to the office of the current PNH director.

Sánchez, the current director of the PNH, says that he maintains the portrait there because “independently of what Bonilla did, he was still the former director of the Honduran police,” in response to Expediente Público’s questions.