*Settlers spearhead initiatives that deprive indigenous people of resources in the Northern Caribbean of Nicaragua, their native region.

**The national economic model imposed on indigenous land is based on a culture of ownership different from that of indigenous people’s communal use of resources, according to human rights defenders.

EXPEDIENTE PÚBLICO

In 2016, during the inauguration of a Green Power property, an African palm oil-based energy plant in the Northern Caribbean, Former General Álvaro Baltodano, delegate for the Daniel Ortega government on investments in Nicargua, declared that 100,000 hectares were available for agro-industrial use in the region.

“African palm oil will be planted on barren land where deforestation has occurred,” said the presidential delegate. Due to climate conditions, African palm is cultivated in the two autonomous regions of the Nicaraguan Caribbean where its rains most of the year.

Currently, there are 5,600 hectares of African palm planted by this company, according to data from the Chamber of Producers and Processers of Palm (CAPROPALMA).

African palm producers say that their cultivation areas are defined by national and territorial authorities. “The palm sector and the national and regional governments have coordinated to guarantee the legitimate use of land and property by all palm plantations. In no way has the activity led to forced displacements of farming or ethnic communities,” indicate producers on the Mesoamerican Alliance for Palm Oil website.

What is true is that in the Nicaraguan Caribbean there is very little land that located within communal territory or protected zones. Lottie Cunningham, director of the Center for Justice and Human Rights for the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua (CEJUDHCAN) warns that of the 304 communities located in the 23 indigenous, Afro-descendent, or special regime territories in the Caribbean, 270 have massive land invasion problems.

Moreover, in the last fifteen years, 1.5 million hectares of Bosawás forest have been lost, particularly protected zones located in indigenous territories, says Juan Carlos Ocampo, director of the indigenous organization PRILAKA.

Read: Familiares de víctimas piden que investiguen a colonos por la masacre indígena en Bosawás

A destructive cycle

For indigenous peoples, settlers are the pinnacle of large national and transnational interests that capitalize on corrupt national, regional, and local authorities, according to statements from judges and indigenous leaders gathered by Expediente Público.

After destroying forests and selling the timber extracted, settlers farm the land and bring in livestock, turning forests into pastures and then fraudulently selling land parcels or rights.

“We know that the Nicaraguan government has promoted the exploitation of natural resources through state institutions,” Cunningham told Expediente Público in a field visit.

“For us, the State has promoted and encouraged extractive activities, just one reason the settlers justify land invasions, especially when we talk about extractive mining and overexploitation of forests which provide for the monocultures of African palm and cattle ranching. Moreover, communities have reported these actions, however, to date, 49 people have been killed, injured, and gone missing (not counting the massacre of twelve Miskitos in August of 2021). All of these cases have been reported to the National Police and the Public Prosecutor’s Office but have not been investigated,” the director of CEJUDHCAN reported.

“These land invasions continue to occur due to impunity,” she says. She continues explaining that “the State has interests in the geopolitical and economic control of our lands and autonomy. However, one way of seeking social justice is legally, as the law establishes rights for indigenous peoples, particularly those pertaining to communal property, which are indefeasible.”

Behind the arrival of the settlers is an economic, political, and cultural mestizo or state model which imposes on Caribbean culture that it does not understand and attacks the ways of its own community, reflects Juan Carlos Ocampo, human rights defender representing PRILAKA.

“We are seeing the expansion of a Nicaraguan economic model which focuses on agricultural exports, increasing cattle ranching, and a monoculture of cocoa and African palm. The Nicaraguan State applies laws to indigenous communities or those who do not have economic means or violent tendencies. It is the groups that participate in cattle ranching that have exercised the law and imposed themselves,” he warns.

“Settlers destroy miles of hectares, but if an indigenous person cuts down tries, he does not receive the same approval from the government,” he says.

Read: Nicaragua: Policía encubre a colonos y culpa a indígenas por masacre del 23 de agosto

More invasions, more investments

Increasing land invasions on communal lands, particularly since 2010, with its highest peak of violence in 2015, coincides with an increase in mining, forestry, and agricultural investments and production in the Northern Caribbean.

Pro Nicaragua, the state investment agency directed by Laureano Ortega, son of President Daniel Ortega and Vice president Rosario Murillo and sanctioned by the international community for allegations of corruption, points out that “the region has extensive land suitable for the production of coffee, cocoa, palm oil, coconut, bamboo, and rubber.”

This amounts to 60% of the mineral resources in the country, according to ProNicaragua. Moreover, the largest number of mineral deposits in the country can be found on the Northern Caribbean coast, with around 388 hectares under metal and non-metal mining concessions, particularly in the municipalities of Rosita, Bonanza, and Siuna. 222 hectares in these municipal territories are being exploited.” This information is false, however, because the company HEMCO alone claims to have 26 concessions in the so-called Golden Triangle which corresponds to 158,590 hectares.

Economic growth should be good news for indigenous people, but this is not the case. Expulsion from land historically used for indigenous subsistence has caused problems not only in terms of physical and territorial insecurity but also with food insecurity.

“The situation is quite serious because there has been a continuous loss of territory and forced displacements of indigenous peoples, causing violence to increase due to land conflicts. We are concerned because there has not been a concrete action taken by the State to reduce the violence to protect the life and territory of communities,” Cunningham says.

A study published by the Center for Justice and International Law (CEJIL) and CEJUDHCAN in 2018 indicated that 23% of children in the Northern Caribbean suffered from chronic malnutrition and 11% were severely mal nourished.

Read: Colonos se organizan en “colectivos” para invadir, depredar y someter territorios indígenas

Extensive cattle farming

To date, there is no data on the magnitude of land invasions nor the quantity of mestiza families in communal territories.

“There has not yet been a mapping of settler farms; the municipalities have not carried out this sort of diagnostic and are only involved in traditional tasks like registration and the legalization process for agricultural products that leave the territories as exports and allow for their commercialization to occur,” Ocampo explains.

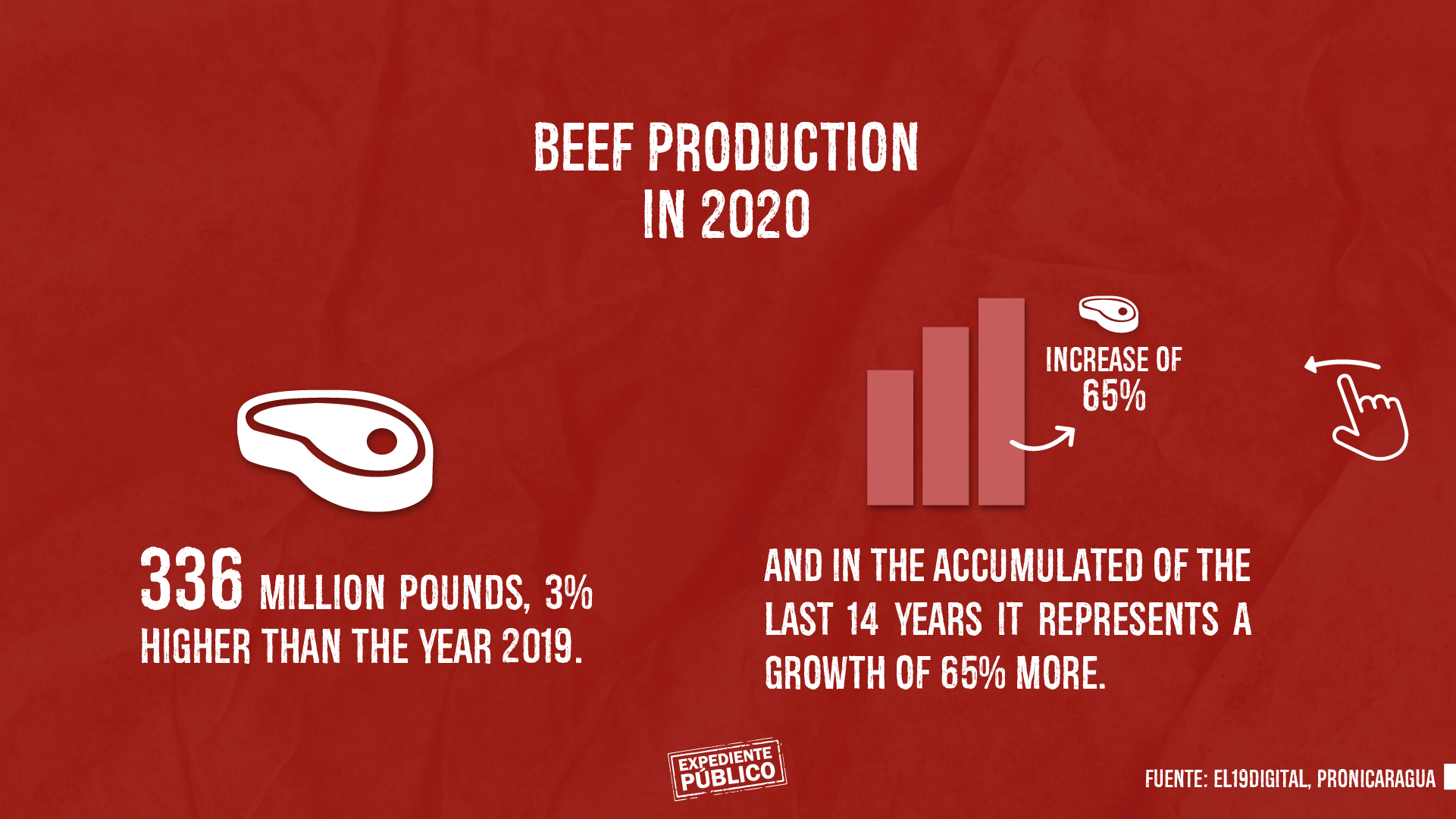

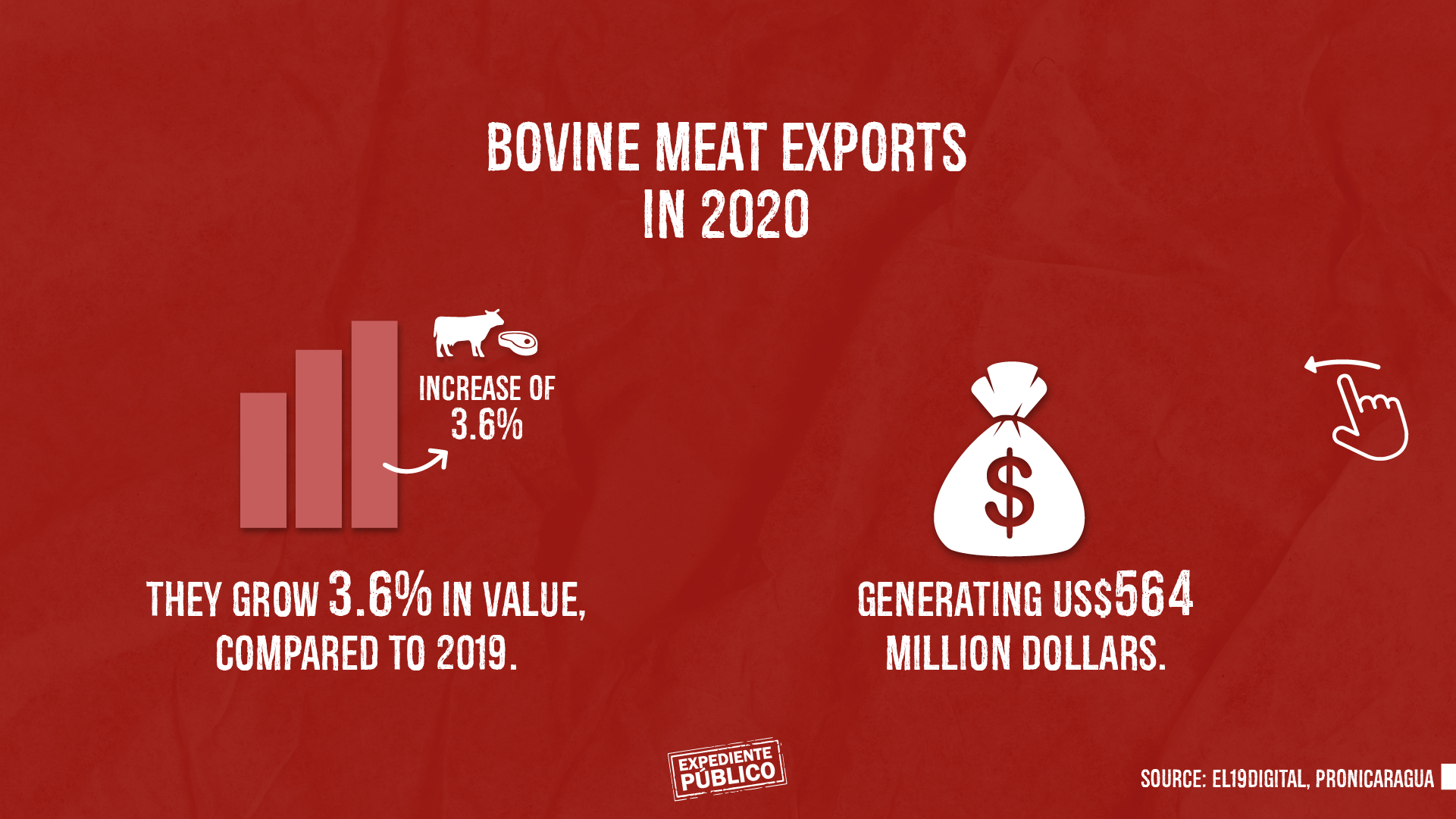

Part of the increase in livestock was propelled by Venezuelan purchases of Nicaraguan beef between 2012 and 2017, with sales greater than 100,000,000 USD each year.

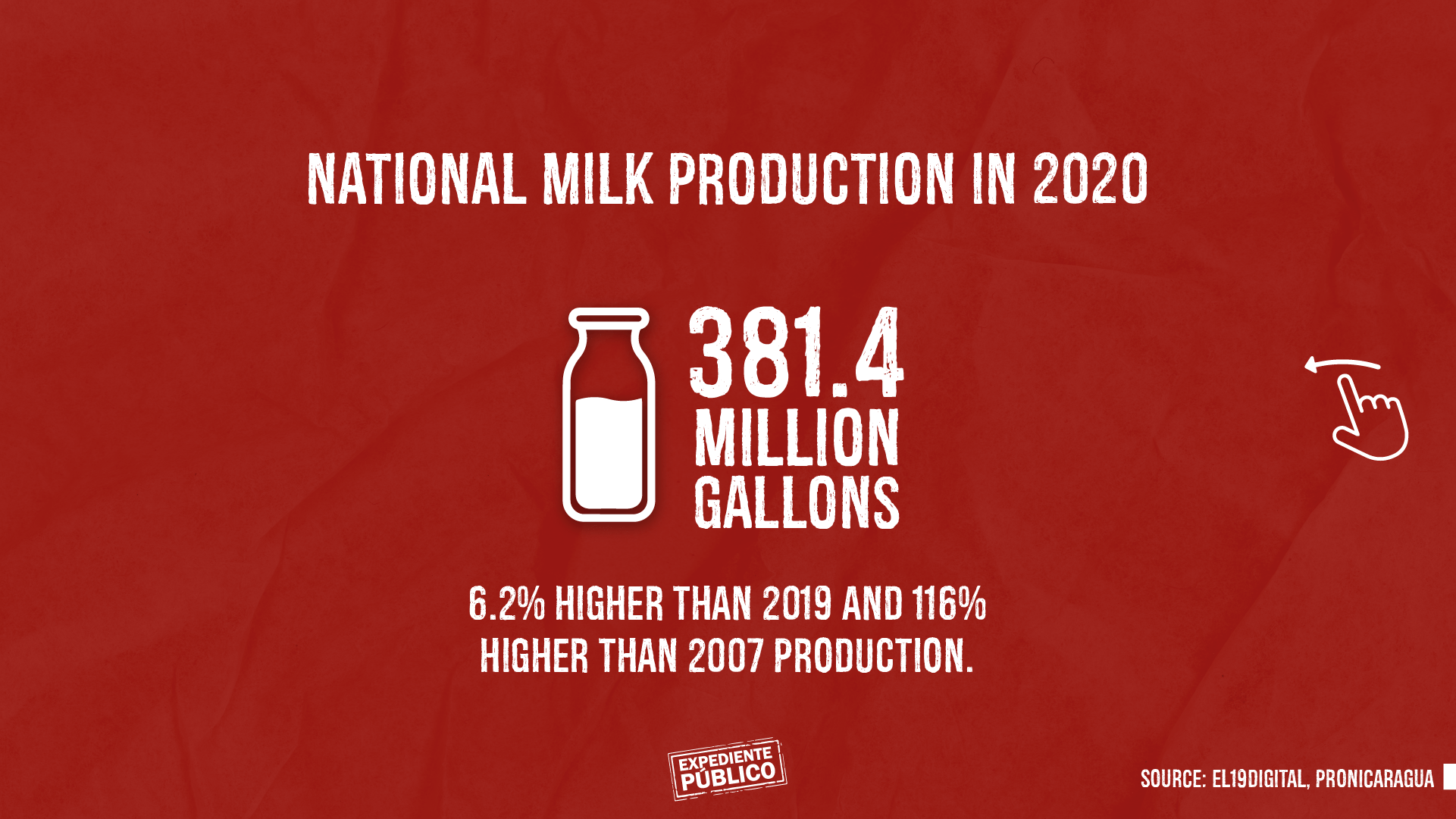

Extensive cattle farming has increased so much in the region that in the last two years two milk collection plants have been installed. One is Lácteos Jerusalén (Mulukukú) and the other is San Antonio (Siuna), where cheeses are produced as well as other dairy products. The Siuna municipal slaughterhouse has also been renovated, and a slaughterhouse in Bonanza was opened.

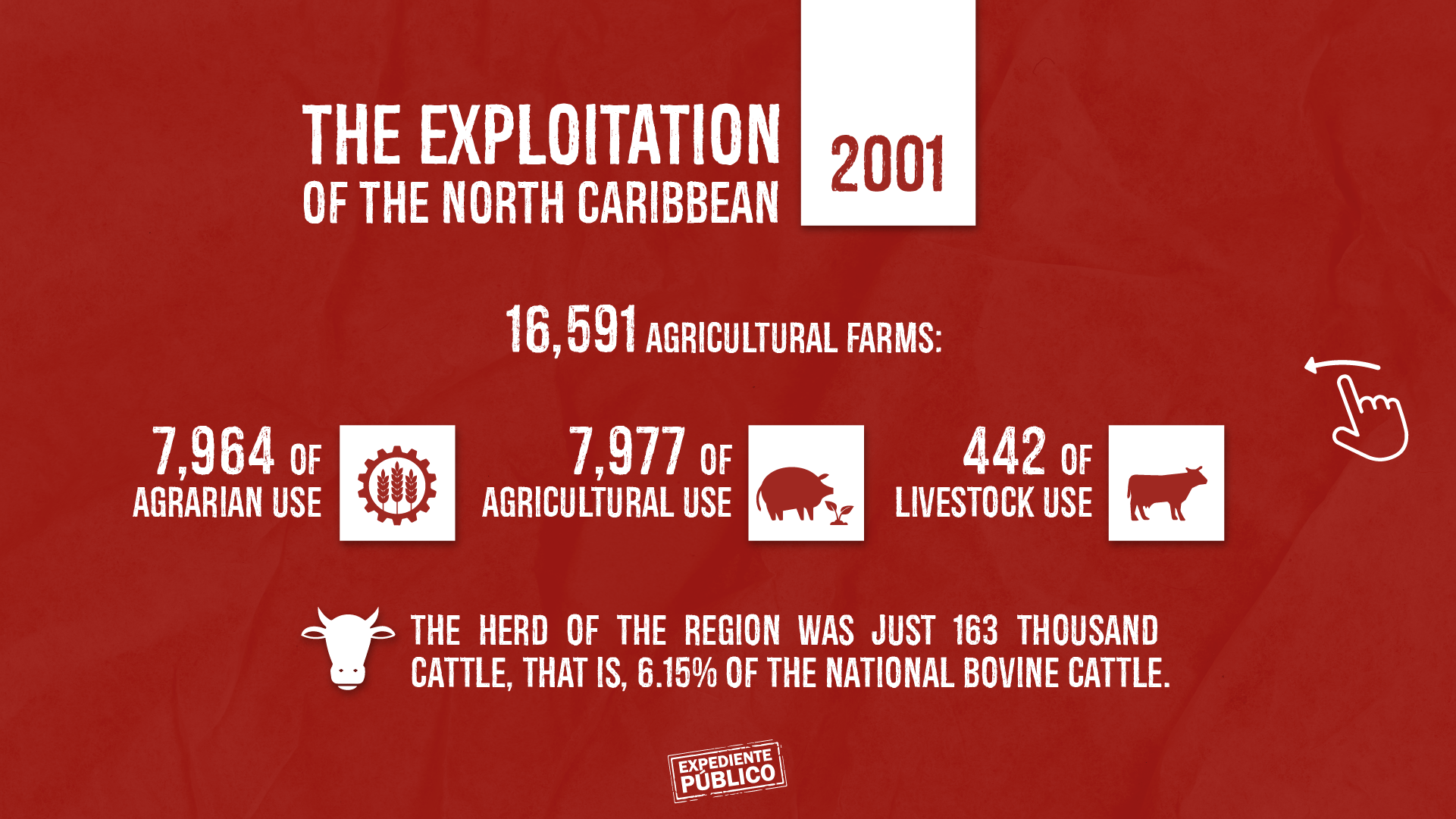

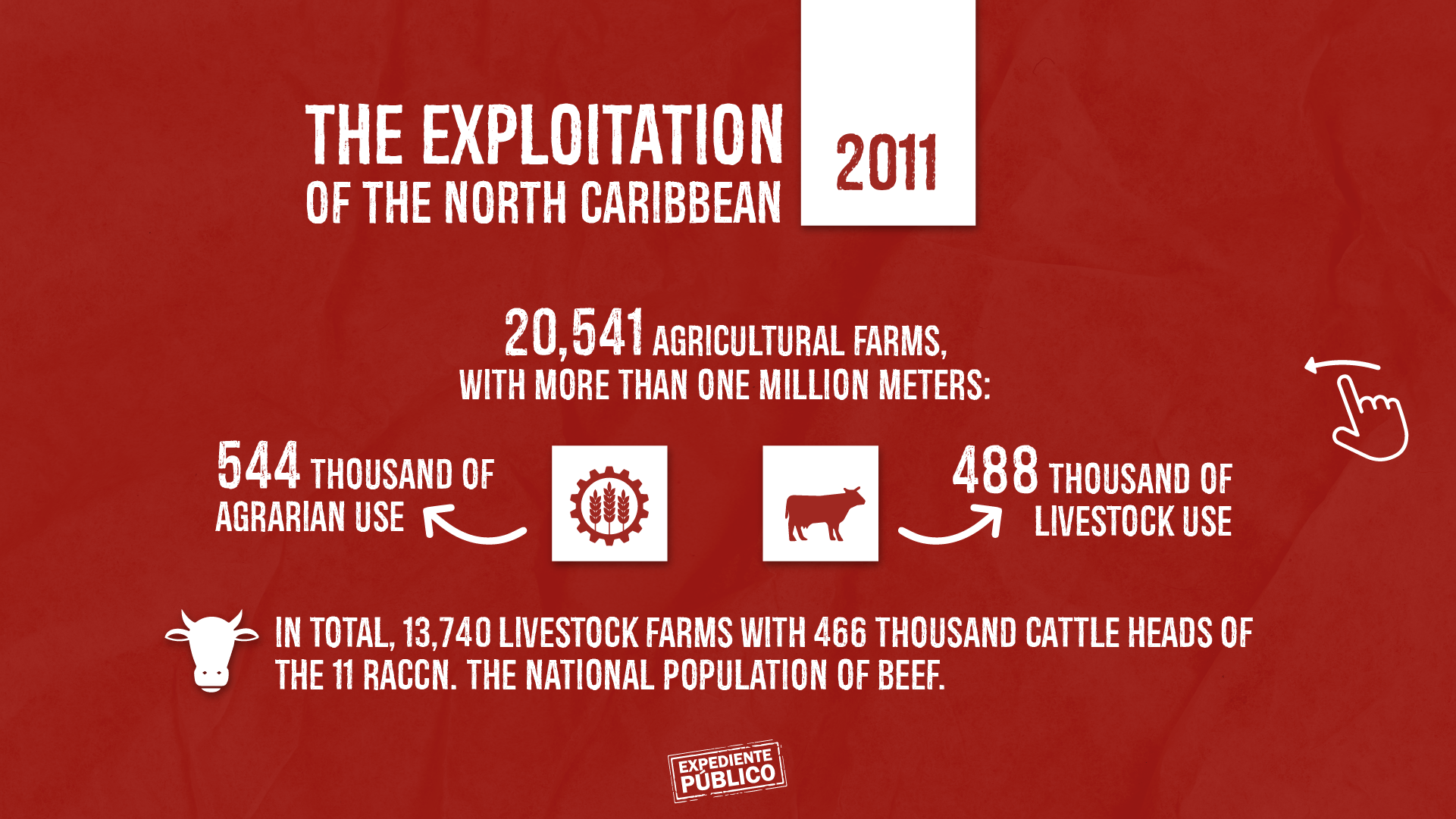

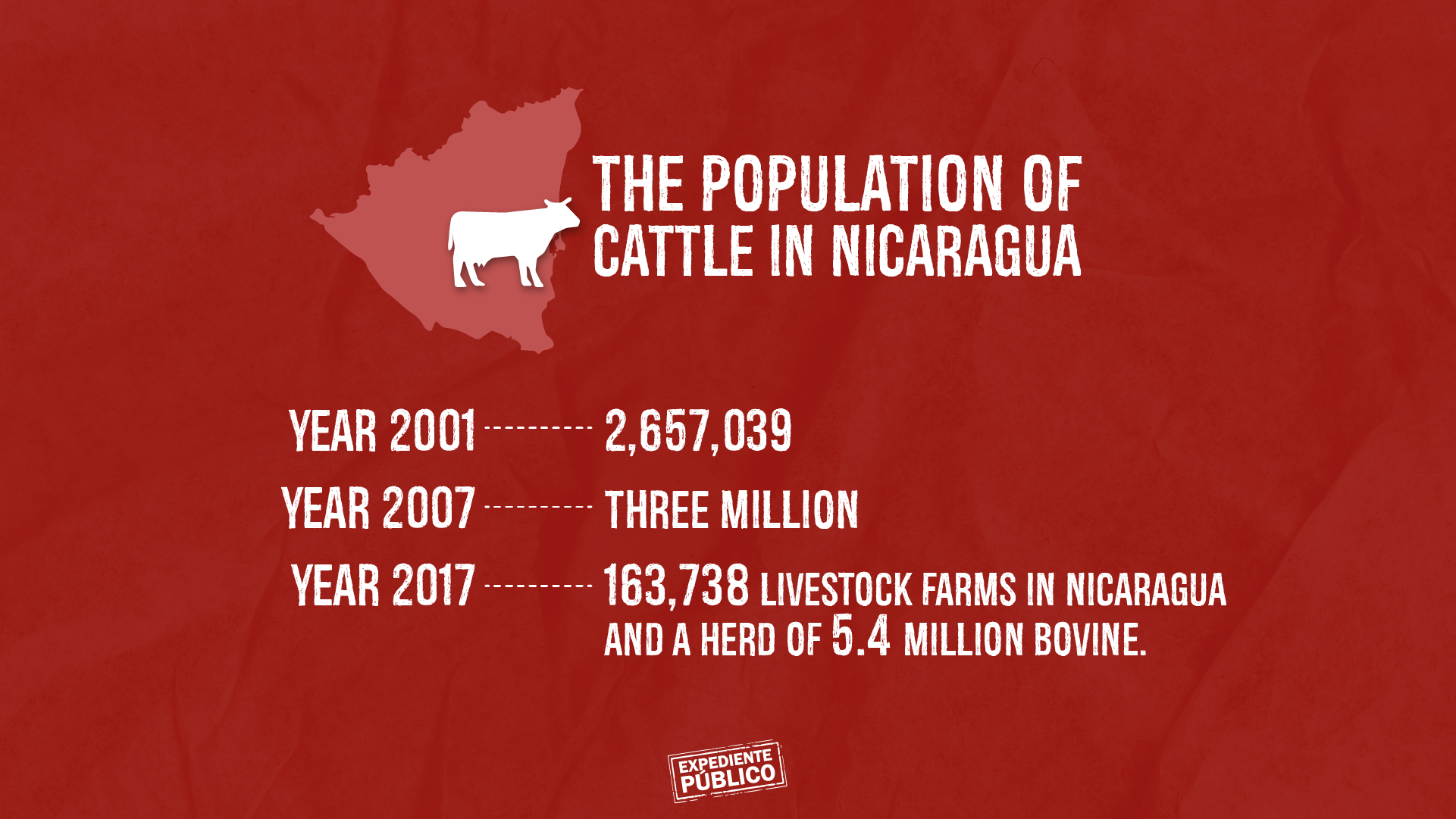

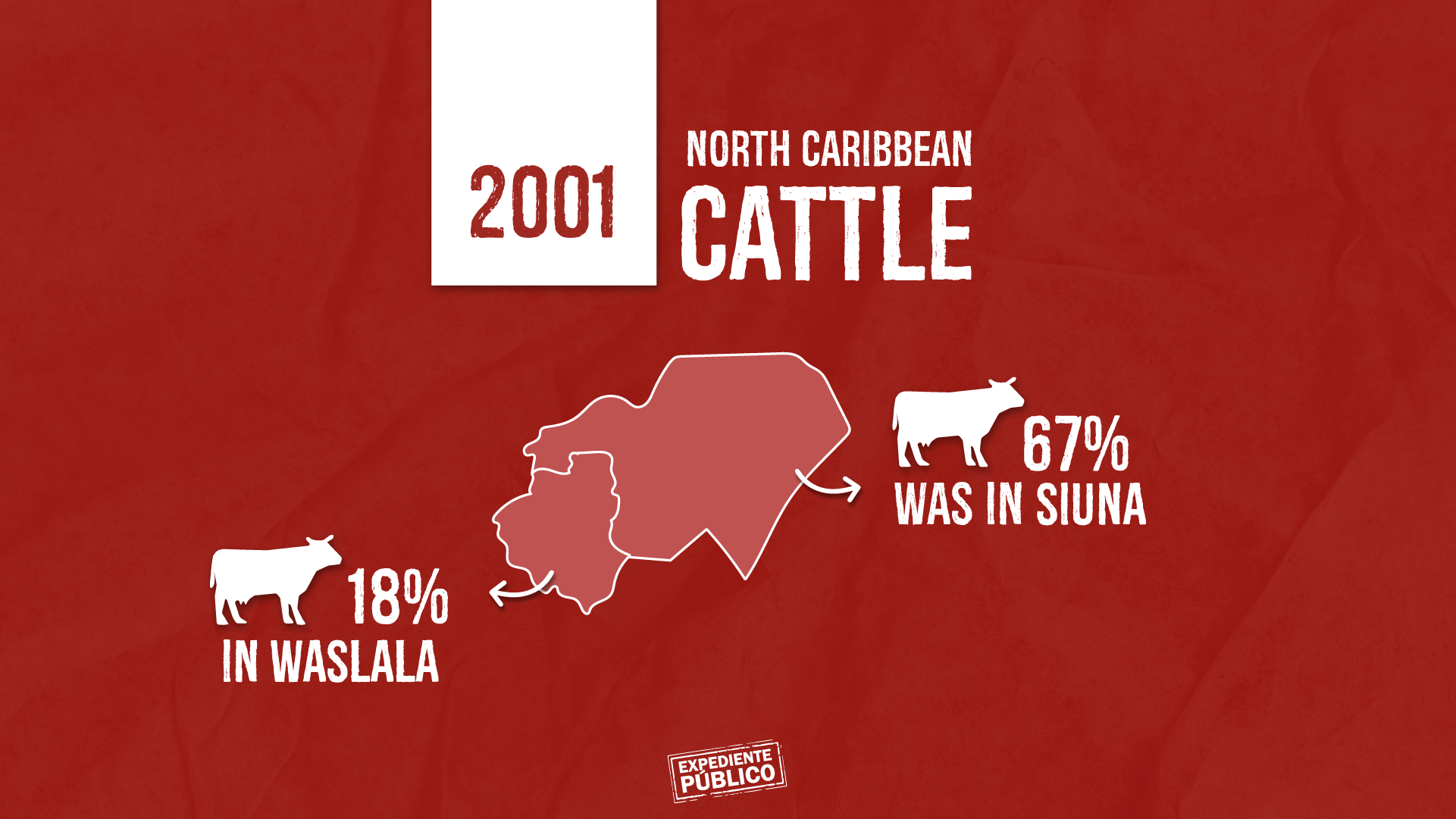

The last agricultural census of 2011 indicated that there were 20,541 farms in the Northern Caribbean, reaching more than one million manzanas: 544 thousand pertaining to agricultural use and 486 thousand being used by livestock. In total, there were 13,740 cattle farms with 466,000 cattle in the RACCN, amounting to a national herd of 4.1 million cattle and the region’s representing 11.2% of the national cattle population, according to the census.

Depopulating, cutting down, exploiting, and reselling

Since 2007, the Sandinista and Daniel Ortega government has favored mining, almost tripling the national production of gold from 100.7 thousand troy ounces of gold per year to 273 thousand in 2020.

Between 2007 and 2020 2,971.1 thousand troy ounces of gold were processed for an average annual production of 212.2 thousand troy ounces, according to the National Plan to Combat Poverty 2022-2026.

“In this same period, the silver production increased to 5,473.0 thousand troy ounces, equivalent to 390.0 thousand troy ounces as an annual average. In 2020, 701.9 thousand troy ounces were produced (+23.4% in 2019 and +6 times the production in 2007 or 109.9 thousand troy ounces),” the report said.

While not all is produced in the Northern Caribbean, three of the six processing plants for artisanal mining are located in Bonanza in the Autonomous Region of the Northern Caribbean Coast (RACCN).

Timber interests have also elevated the environmental crisis in the area. In 2009, the company ALBA Forestal was created and formed part of the consortium ALBANISA, headed by Francisco López, treasurer of the Sandinista Front. Research by Divergentes y Conectas indicates that until 2016, when it shut down operations, the company generated 5.8 million dollars from five million cubic meters of timber extraction.

In 2013, the company also initiated operations in the Golden Triangle through MLR Forestal of Canadian, American, and Nicaraguan capital. By April 2021, it held more than five thousand hectares of plantations, especially of cacao and teak wood.

An investigation from the Oakland Institute reveals one of the shareholders of the agroforestry company and partner in HEMCO, Randy Martin, as an important investor in Nicaraguan mining companies.

“The company aims to obtain 6,700 hectares, divided into 1,500 hectares of cacao, 3,000 hectares of teak wood, and 2,300 hectares destined for conservation,” the website says.

Robusta coffee is one of the crops being grown in the Nicaraguan Caribbean, according to the Robusta Coffee Producers Cooperative of New Guinea (COOPRODECAR). Moreover, the Del Monte industry has been preparing to produce pineapple and plantain in the area.

Read: Indígenas en Nicaragua: conquista y colonización en pleno siglo XXI

Untamed capitalism versus indigenous idiosyncrasy

Northern Caribbean land is protected by Autonomous Law (28) and the Communal Property Regime of Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Communities in the Autonomous Region of the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua and the Rivers of Bocay, Coco, Indio, and Maiz (445), where the spirit of communal properties is established.

«The demarcation and titling process has advanced to the fourth stage, but there are five stages, with the last one being that of sanitation, having to do with third parties occupying land illegally,» said Cunningham.

The defender reiterates that “when we talk about land regulation, we are talking about people who have occupied the land illegally and have to abandon it so that indigenous communities can resume use, occupation, and control of their territories. Nevertheless, the Nicaraguan State has omitted this last phase.”

Ortega is a socialist president with an anticapitalism discourse. However, his economic policies have proven to favor multinational companies, free trade zones, and private companies: all detrimental to farmers, community leaders, and indigenous peoples, as in the case of the canal project.

Juan Carlos Ocampo from PRILAKA considers the conflict to be rooted in the disregard for indigenous communities in the Caribbean and their ways of life contradicting state economic models.

One example of these socioeconomic differences is the sense of community in “sharing a physical space” that is not necessarily defined by ethnicity. Many communities, principally indigenous or Afro-descent, establish themselves in a specific territory. Their life development is particularly different from that which the State imposes on them, Ocampo states.

Read: Misquitos, acorralados en su propia tierra

The family is the nucleus of society, however, for indigenous peoples, a community serves this same purpose. The way in which indigenous people make decisions is through a community assembly or a meeting between the sons of the community who discuss and debate to reach a consensus.

This participatory democratic model has survived, even though since the post-war era of the 1990s, voting is done by a show of hands and secret balloting due to threats or political conflicts. However, these forms of decision making are not proper to indigenous culture. “We have not adapted to these forms of decision making, which is why they have been used as a way to vitiate historical decision making,” Ocampo says.

“Another element that differentiates us from any other community is the idea of collective property: the space that we occupy does not just belong to a specific person but instead belongs to all community members. We have the right to usufruct. The place where my family farms has a general area where everyone has access to timber and can hunt. I am not the owner, rather the community owns the land. This type of property is lasting because it allows for social relationships, basic economic needs to be met, and development possibilities for everyone. When lands are privatized, hoarding and inequality take shape, generating more conflicts,” he adds.

There are other economic models that have lasted throughout the years, such as bartering and other types of social capital like “pana pana,” where community members go out and assist each other in planting crops, among other activities, so that parties involved mutually benefit without the need for payment or some type of retroactive obligation.

«An indigenous person is not a ‘worker,’ as he does not have the mentality of an employee. Instead, we are ‘managers’ of our own lives and the livelihoods that allow us to make ends meet for our families,» says Ocampo.

«It is not part of our culture to do away with forest life and go work for a settler or a company. This is not because Miskitos are lazy. In our community, everyone is looking for a way to make a living,» he adds.

“Settlers do not understand the concept of collective property. For them, the community authority figures are the landowners, disregarding the idea of a community assembly. The mestizo or state economic, political, and cultural model imposes itself on Caribbean culture and does not make an effort to understand it, ultimately attacking the community’s ways of life,” he concludes.