*The initial list of layoffs presented by the former minister of security only included mid-ranking police officers, says Eric Olson, director of policy and strategic initiatives at the Seattle International Foundation and fellow at the Wilson Center.

**During the Hernández administration, the government considered closing the Honduran National Police while militarizing public safety measures.

Expediente Público

As was the case in previous processes, the 2016 removal of police officers gave rise to a scandal. The New York Times revealed that 25 police officers, including leadership, were involved in the murders of former members of the Directorate for the Fight against Drug Trafficking, Arístides González and Alfredo Landaverde.

Even though the institution could have let go its own police officers, the government did not trust the police. For this reason, President Juan Orlando Hernández decided to create the Commission on Refining and Transforming the Honduran National Police to remove police officers and assigned only those whom he completed trusted: his minister of security, Julián Pacheco; former Supreme Court Judge Vilma Morales; Alberto Solórzano, president of the Evangelical Christian Fellowship of Honduras (CEH); and Omar Rivera, advocacy coordinator at Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa (ASJ), a Transparency International (TI) chapter in Honduras.

A comprehensive cleanup

“Former President Hernández was willing to let the process play out, due to mounting pressures from civil society and the media to clean up police ranks,” remembered attorney and director of the National Convergence Forum (FONAC), Omar Rivera in an interview with Expediente Público. The FONAC is a civil society organization created to follow up on the National Plan of Honduras.

Read: Los retos del Gabinete de Honduras: seguridad y sector social los más críticos

Former President Hernández, currently accused by the US of large-scale drug trafficking, supposedly wanted to clean up the institution. However, an investigation published by the Wilson Center showed how the Honduran government tried to influence the police removal process.

“In the commission’s first meeting, the former security minister, General Pacheco presented a list of those who would be removed from their duties at the PNH. At the time, all the commissioners had threatened to resign if the government interfered politically,” explained Eric Olson, who coordinated the study published by the Wilson Center and is currently director of policy and strategic initiatives at the Seattle International Foundation (SIF), in an interview with Expediente Público.

The list that General Pacheco presented left out PNH leadership exposed by the New York Times’ 2016 reports on the murders of former members of the Directorate for the Fight against Drug Trafficking, Arístides González and Alfredo Landaverde. Pacheco included just 32 police officers, most of them of mid rank.

“Support from the US was essential to the process, especially because the Americans protected and prevented us from being subject to political pressures or threats by organized criminal groups,” remembers Rivera, who, like the rest of the commissioners, received constant threats throughout the removal process, to the point that the government had to grant him protection through the Military Police of Public Order (PMOP).

After successfully removing 43% of police elites, the commission evaluated the rest of the police force, which had reached 13,657 officers in 2016.

Read: Honduras: el ministro de Seguridad que podría plantar cara a la criminalidad

To avoid being manipulated by the PNH, those involved in the cleanup asked the former Directorate of Investigation and Evaluations of the Police (DIECP), the Public Prosecution Service and the Attorney General’s Office (PGR), the Supreme Court (CSJ), the Honduran National Audit Office (TSC), the National Banking and Insurance Commission (CNBS), and the National Commission on Human Rights (CONADEH) to provide incriminating information on officers.

“The American ambassador also offered information on police officers’ involvement in illicit activity. The US saw the process as an opportunity not only to purge police ranks but also to strengthen the institution,” added Olson.

The 41-million-dollar cost

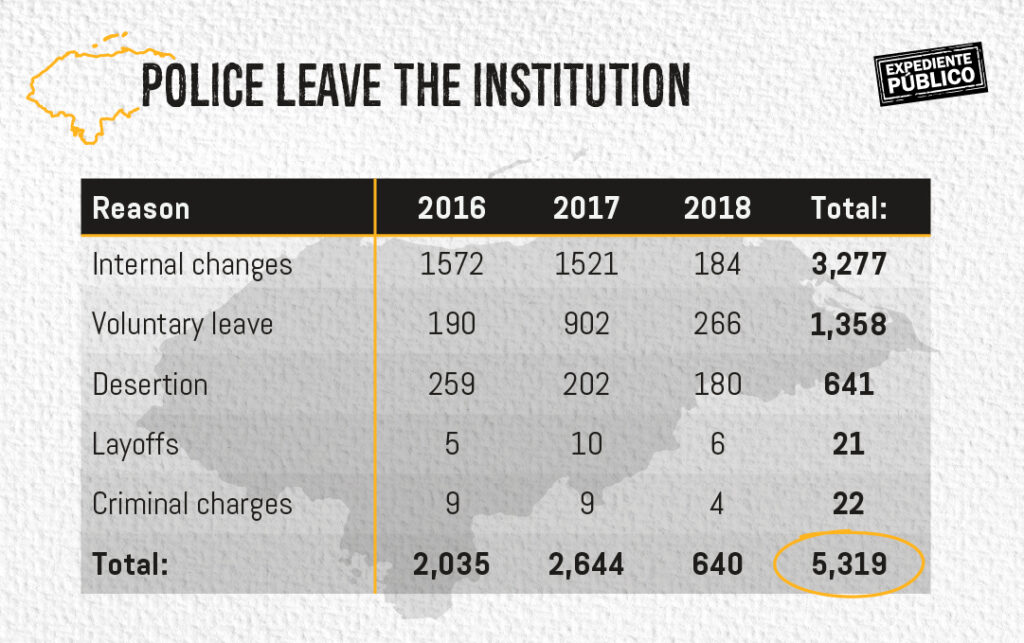

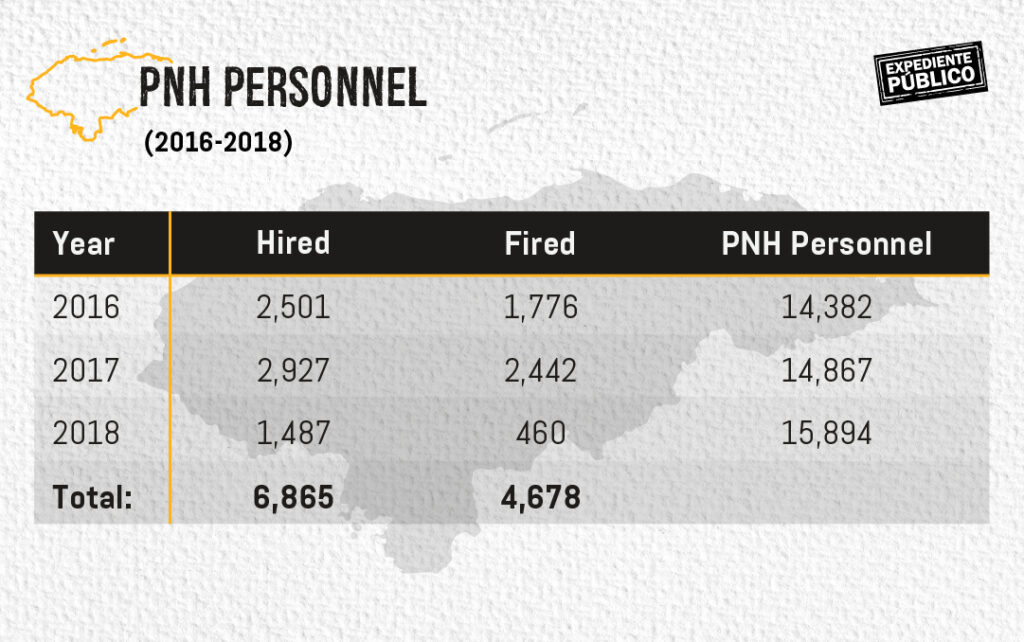

During its first year, the commission removed 1,776 police officers. The commission removed 2,442 police officers in 2017 and 460 in 2018. Another 641 officers deserted the institution from 2016 to 2018. In total, the PNH lost 5,319 officers, or 38% of its personnel during this period.

During the institutional cleanup, of the 4,678 police officers removed, excluding those who deserted the institution, 8.5% were of high rank, 4.5% were midranking, and 87% were basic agents.

Not all police officers were removed for having committed crimes. 66% of officers were laid off because they did not meet standards of suitability, for example, for being overweight or of old age, having a bad temper, not knowing how to read and write, or failing to exhibit basic skills required of police officers.

To compensate those let go by the commission, the Honduran State spent several million lempiras (around 41 million dollars) in police benefits. On average, without considering the different positions held individually, each officer received 214 thousand lempiras (8.6 thousand dollars).

Read: Honduras: informe del Congreso Nacional expone sistema de justicia al servicio del narcotráfico

“Money saved from layoffs was used toward benefits. The benefits did not cost the State a cent,” according to Rivera, who represented Asociación para una Sociedad más Justa (ASJ), an organization identified as having politically supported the Hernández administration, especially as part of the commission.

Despite many police officers’ leaving during the three-year removal process, the institution also hired 6,865 police officers, meaning that the police force increased by 16.3%, from 13,657 police officers in 2016 to 15,894 in 2018.

More oversight necessary?

Director of the PNH Commissioner Gustavo Sánchez considers that while many police officers were let go by the commission, others were “very good, had ability and experience, and were generally people that would have kept those who committed illicit activities while at the institution from doing so.” The Commission on Refining and Transforming the PNH approved of Sánchez and his current position.

According to Sánchez, the removal process could have been done internally without an external commission. “The institution had the legal means to carry out such a process, but there had always been an interest in maintaining the PNH in a distant, anxious state.”

For Oscar Rivera, one of the four former commissioners in charge of the layoffs, the police had the legal means to carry out such a process but did not have interest in exhausting them. “The police never did anything internally. Civil society removed police officers because the institution was not willing to do so, even though there were many police officers who were willing to make the process more comprehensive.”

At the time, the former attorney general and current transparency minister, Edmundo Orellana stated that it would be “absurd” for the police to conduct this sort of process internally. Of this opinion was also the former President of the UNAH Julieta Castellanos, who argued that “the institution never carries out this process internally because police officers know each other too well.”

As Eric Olson previously voiced, if in 2016 the purging of police ranks had been left in the hands of the institution, the process would have failed. “The police normally use have their own oversight mechanisms, but officer layoffs cannot be limited to such a system, as certain players intentionally seek to weaken the institution.”

Read: Periodistas bajo censura, muerte, impunidad y criminalización en Honduras

An example of how internal oversight mechanisms for police layoffs do not work is the experience of the Directorate of Investigation and Evaluations of the Police (DIECP). Between 2012 and 2016, the agency removed a mere 227 low-ranking police officers from duty. Despite these poor results, the State spent 221 million lempiras (8.7 million dollars) on the agency’s daily operations.

Due to the failure of the DIECP, one of the first decisions that the commission made was to create the Division of Disciplinary Action (DIDADPOL), which was responsible for investigating infringements within the institution.

Remilitarizing security efforts

According to Sánchez, in addition to overseeing the police force, the Hernández administration used the removal process to remilitarize public safety through the PMOP, where 5,000 soldiers were hired to carry out tasks that normally fell under the jurisdiction of the police and the National Interinstitutional Security Force (FUSINA), “which was created to serve in parallel with the police.”

Former Commissioner Rivera rejected the affirmations made by the director of the PNH and argues that police layoffs were not related to an overall remilitarization of public safety measures. “The idea of the military as a protagonist originated several years ago and should not be considered as relevant to understanding police dismissals.”

Sánchez and Rivera agree that the Hernández administration considered abolishing the police force. “There was a moment where the government considered that with so much corruption, the PNH had to go. I am not sure if the president held this opinion, but many in his government did. Fortunately, this consideration never came to fruition,” said former Commissioner Rivera.

Even though the institution survived attempts by the government to shut it down, the Hernández administration did weaken the police force. “President Hernández came into office understanding that he could not trust the police and thought that the police had the ability to destabilize his government,” commented journalist and analyst, Óscar Estrada to Expediente Público.

Read: Más inversión en seguridad y defensa, mayor pobreza en Honduras

Amid an institutional crisis and part of a Latin American tendency to militarize public safety, the Honduran government created, in 2013, the PMOP, a police force subordinate to the armed forces that eventually reached 5,000 officers. That same year, the government created the FUSINA, a military unit that coordinated police duties.

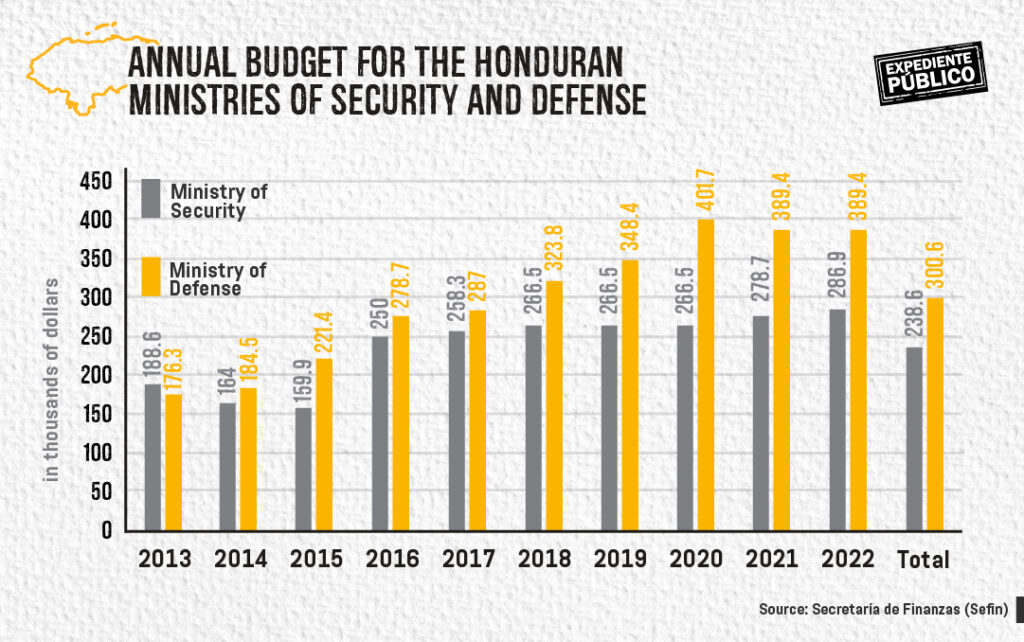

One way to observe the remilitarization of the public security sector is through an analysis of the budget. Before 2013, security expenditures were less than defense spending. However, the creation of the PMOP and the FUSINA changed this tendency. Beginning in 2014, which was Hernández’s first year as president, government expenditures in public safety surpassed defense spending.

Despite the remilitarization of public safety, the police’s decline during the eight years of Juan Orlando Hernández’s presidency was relative, since the budget of the Ministry of Security increased by 70%, from 4 million lempiras (164 million dollars) to 6.8 billion lempiras (278.7 million dollars), annually. Even though the PNH no longer carried out all its previous responsibilities, government spending in security increased.

In her plan to dismantle what she inherited from the Hernández administration, President Xiomara Castro returned some functions to the PNH, including oversight of the 25 prisons in Honduras and management of the National Anti-Maras and Pandillas Task Force (FNAMP), along with the National Task Force on Secure Urban Transportation (FNSTU), which were both previously responsibilities of the military.

Civil society and international organizations support demilitarizing the public security sector. Not even the military is opposed to returning to their barracks “because neither clean nor dirty officers will lose their privileges or businesses,” said Óscar Estrada.

In 2012, the CRSP also recommended the demilitarization of the PNH, considering that since 1998, the institution has maintained elements of military doctrine in its trainings, operations, and overall essence.