*In the case of dictatorships or autocracies, institutions for civic involvement are created by the government to manipulate citizen participation, warned the political scientist and Cuban historian, Armando Chaguaceda.

**Nicaraguan expert sees patterns between certain regimens that are showing signs of authoritarianism and the hollowing out of democracy in Central America and beyond.

Expediente Público

The Xiomara Castro government’s intention to create a National Roundtable for Citizen Participation, according to a bill sent to Congress on September 21, has created déjà vu regarding the risks of the initiative, such as spying on and manipulating the population. This very phenomenon has occurred in Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela, countries with which the current administration has a known political affinity.

“Mechanisms for democratic participation exist within dictatorships and democracies. They are ways in which citizens directly participate in the public aspect of government administration: through assemblies, referendums, and other formats,” the political scientist and Cuban historian Armando Chaguaceda said to Expediente Público in an interview.

But “in the case of dictatorships or autocracies, these institutions are not created to widen citizen participation but rather, to manipulate it. This is the phenomenon that other authors have called “participacionismo,” added Chaguaceda.

In these cases, citizen participation is not autonomous because it is always invoked by the State or the governing party, and people “are political sympathizers, instead of citizens with pluralistic ideas,” according to the Cuban political scientist.

The principles of this “participationist” view, which manipulates democratic mechanisms for direct participation, above all in local spaces but also in large referendums or plebiscites, have existed in contemporary politics for quite some time and are very characteristic of authoritarian regimes and populist governments,” the historian expressed.

For Chaguaceda, “this is the context of the instrument, despite the differences between the case at hand and other regional experiences such as communal councils in Venezuela, assemblies of popular councils in Cuba, and citizen councils in Nicaragua.”

Read: El Salvador y Honduras llegan a la OEA con claros síntomas de “gripe” antidemocrática

Vertical hierarchy

The preliminary draft of the citizen roundtables project would eliminate the National Forum for Convergence (FONAC in Spanish), which Is the current national instrument for dialogue that calls together 22 civil society organizations and political parties.

The FONAC receives a government budget and is presided over by the head of the executive branch, who designates a secretary who receives a salary for his or her work. Assemblies are convoked by the executive branch or by more than half of the member organizations.

With the new initiative, the costs of the Roundtables for Citizen Participation would be absorbed by the recently created Office of Strategic Planning, whose head will be the coordinator of the roundtable. The president of Honduras will convoke the member organizations.

Although the FONAC has been criticized for its role during the Juan Orlando Hernández government, the vertical nature that exists within the new law for citizen roundtables does not bode well in a government that is inclined to favor socialism of the twenty-first century.

Read also: Cuba, Nicaragua y Venezuela son las maquinarias autoritarias que producen mayor migración

Countries with similar patterns

“The crisis in the region has helped us to discern or relate to certain scenarios,” a Nicaraguan analyst commented to Expediente Público in an interview where he asked for anonymity for security reasons.

“I am observing in Central America and beyond patterns similar to those which other countries and regimes have adopted previously,” he continued.

This is the case of the Venezuela, with the government’s mechanisms of sociopolitical control, which are very similar to the repressive structures that Nicaragua and Cuba have,” added the Nicaraguan expert.

Moreover, the expert said that “laws of control or repression share similarities across regimes,” pointing to Nicaragua and Russia as examples.

He also referred to the case of the Law of Foreign Agent Regulation, which was approved in Nicaragua and is now being embraced by (Nayib) Bukele” to control non-profit organizations in El Salvador.

“To avoid pointing to authoritarianism and a breakdown of democracy, I really do believe that we cannot rule out the effects of different regimes on other countries. One country observes another that has had certain levels of success,” the anonymous expert said.

In the case of Honduras, “it is healthy for civil society to be alert” to all of the possibilities resulting from the roundtables for citizen participation. Otherwise, the metaphor that political scientists use could apply: “Slowly get to know the frog, and she will not know and soon die.”

The Nicaraguan expert said that some alarm signals that should be considered are inconsistencies in laws, failing to include the opposition, and disrespecting the plurality of participatory spaces. “These are symptoms of an unfavorable outcome, that could at some point, become exclusionary in nature and turn into an apparatus for polarization,” he added.

Read also: Honduras se vuelve cómplice de Rusia y Nicaragua

The CPCs of Nicaragua

Following his rise to power in 2007, Daniel Ortega “bet on the consolidation of his hegemony not only regarding horizontal power,” with the concentration of leadership on different fronts to gain predominance in the Legislative Assembly, “but also in the vertical hierarchy of the territories,” according to an analysis published in “La insurrección cívica de abril” of 2018.

According to the publication, that same year, with the approval of an executive decree that “beg(an) the process of dismantling municipal autonomy and the involution of advances in decentralization (…), designing policies for citizen participation throughout national territory through the Councils for Citizen Power,” also known as the CPCs, the government dismantled the modalities and structures already in existence.

The CPCs are “a single-party participation channel” oriented toward reconstructing the political hegemony of the FSLN at the grassroots level,” according to the same analysis.

“The CPCs were a form of direct organization promoted by the government that was going to have different functions related to topics of interest for citizens, such as health, education, citizen security, and public services,” Nicaraguan expert in security, Elvira Cuadra commented to Expediente Público in an interview.

Among its members were those who formed part of other social organizations. However, “as the Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo regime showed its authoritarian face, fewer people participated in the CPCs,” said the expert, for whom these councils, in the beginning, were not paid much attention, even though they “were conceived and installed with the objective of becoming mechanisms of control and surveillance.”

That role became even more pronounced during the sociopolitical crisis of 2018 in Nicaragua. “The CPCs had become vigilantes and those who reported community members suspected of opposing the government,” Cuadra said.

Read: Xiomara Castro en Naciones Unidas intercede por dictaduras de Cuba y Nicaragua

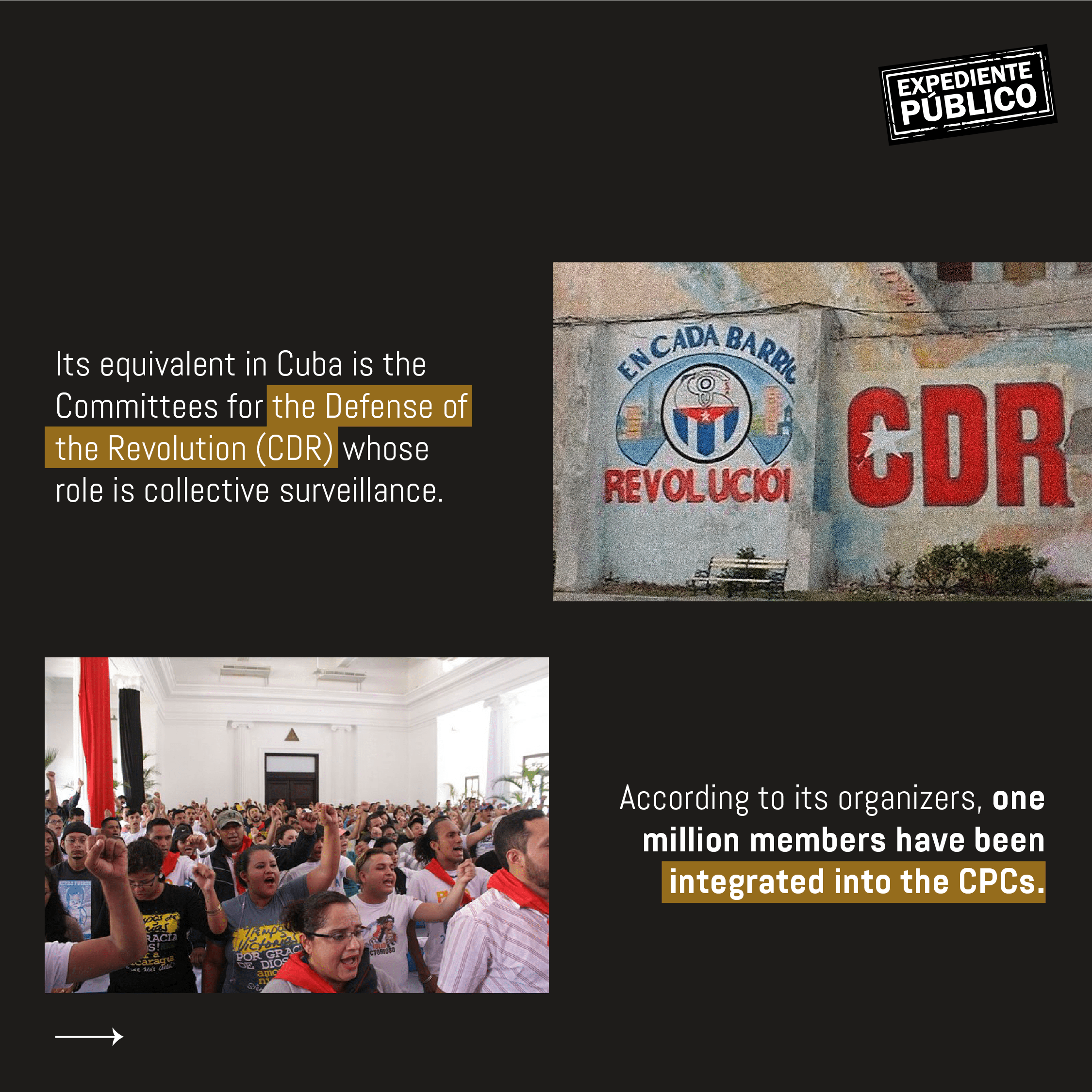

Popular Power in Cuba

In 1986, the approval of the Law of Popular Councils took place. Its expansion at the national level began between 1988 and 1992.

Similarly to the communal councils in Venezuela and the CPCs in Nicaragua, the people’s power is a model of participation “with a bias not of empowerment but of ‘participacionismo,’ the historian Chaguaceda points out.

These members and leaders of the CPCs were the political supporters that the regime in Nicaragua used to attack the protests that began in April 2018 and, in just a few months, left 355 civilians dead at the hands of shock troops and paramilitary groups, many of which are members of these organizations.

In Cuba, “citizens are not recognized as a actors in a pluralist system but rather, the social base of the governing party, where there is no autonomous participation but instead, means of consultation, where the mechanisms of participation that we have defined as local assemblies are turned into transmission lines through which the governing party gives orders, mobilizes, and distributes resources,” he explains.

The idea of communal power in Venezuela

“The idea of communal power in Venezuela began during the government of President Chávez Frías, even though the Constitution that was approved by means of a referendum in 1999 did not include any reference to the term,” according to the Venezuelan journalist, Javier Mayorca, who spoke to Expediente Público in an interview.

In 2007, with the proposal to reform the constitution, Chávez “looked to disrupt the distribution of public services” between the national, state, and municipal levels, “doing away with state jurisdictions and obligating the municipalities to transfer their jurisdictions to the Communal Councils,” according to academic analysis. Venezuela supposedly substituted a representative democracy for a participatory democracy.”

The constitutional reform was rejected by the majority of the population, but the communal councils had already been created in 2006 outside of the constitution.

They had the ability to to determine important matters, “for example, if a square within a certain jurisdiction could be used for political acts” or “if a person could have access to housing projects,” Mayorca explained.

Some opponents saw an opportunity and began to participate in the processes of gestation for such committees to dispute power quotas pertaining to the ruling party, but the government sooner rather than later became aware of this move and began to deny requests to opposers and independents, Mayorca remembers.

He explained that the communal councils also had the task of controlling the police, “as a form of popular power,” according to the narrative of the ruling party.

This role held by the councils is reminiscent of the recently inaugurated roundtables for citizen security during the government of Xiomara Castro. In any case, the tasks of the communal councils are varied and increasing,” the journalist said.

President Nicolás Maduro, who has been in power since 2013, has tried to empower even more communal councils under the understanding that if the state and municipal elections, which are indeed official authorities of power recognized in the constitution, do not result in his favor, he could use communal power to go over their heads,” Mayorca analyzed.

But the economic crisis in Venezuela, which has caused the ruling party to lose much of its grassroots support, has also been a reflection of the social base. It has led to clashes over specific issues such as the distribution of subsidized food that, at one point, as well as fuel, was a large source of economic income.

The communal councils, which are perceived as instances for political campaigning, were commonly activated before elections and during elections to mobilize voters, distribute food to benefit pro-government voters, and coordinate all of the organizational logistics necessary to win an election, the journalist explained.

Venezuelan collectives are to repress

But in addition to these councils, the Venezuelan government has also promoted the creation of “colectivos” or militant groups with a particular ideological backing, which have pushed back against anti-government protestors, similar to what happened in Honduras with the protests, composed mostly of public employees, in favor of President Hernández.

“People view “colectivos” in a negative light. They are fearful because the militant groups can conduct violent acts on the population, and they are worried because “colectivos” also function as political and social authorities,” according to Mayorca.

Another parallel with the “colectivos” that in Honduras identify with the ruling Libre Party is that in the past, they have been attributed to damage caused to private property and during the current government, protests demanding employment and a series of land invasions.