Expediente Público

The primary elections in Honduras will take place on March 14, despite a general lack of confidence in the electoral system. The three predominant political parties in the country will participate and choose their candidates for the November 28 general elections.

The March date will represent a political push from parties who will evaluate their candidates and reach an agreement internally. The primaries will also be a test of either transparency or fraud for the Honduran electoral system, in the wake of the general elections that will choose the successor to the controversial President Juan Orlando Hernández (2014-2022).

More on this: Honduras: The Public Prosecution Service and its Legacy of Impunity and Injustice

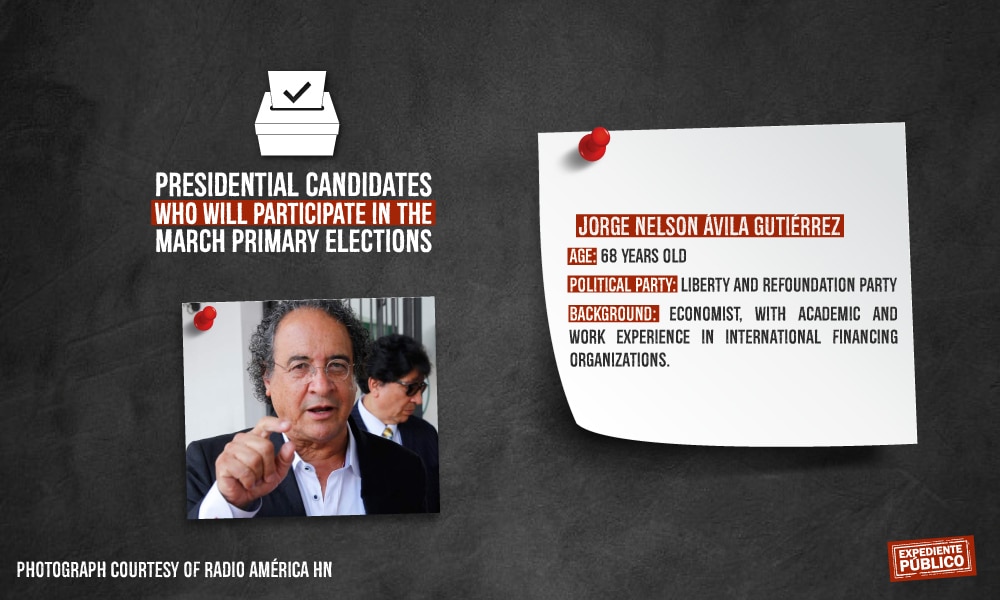

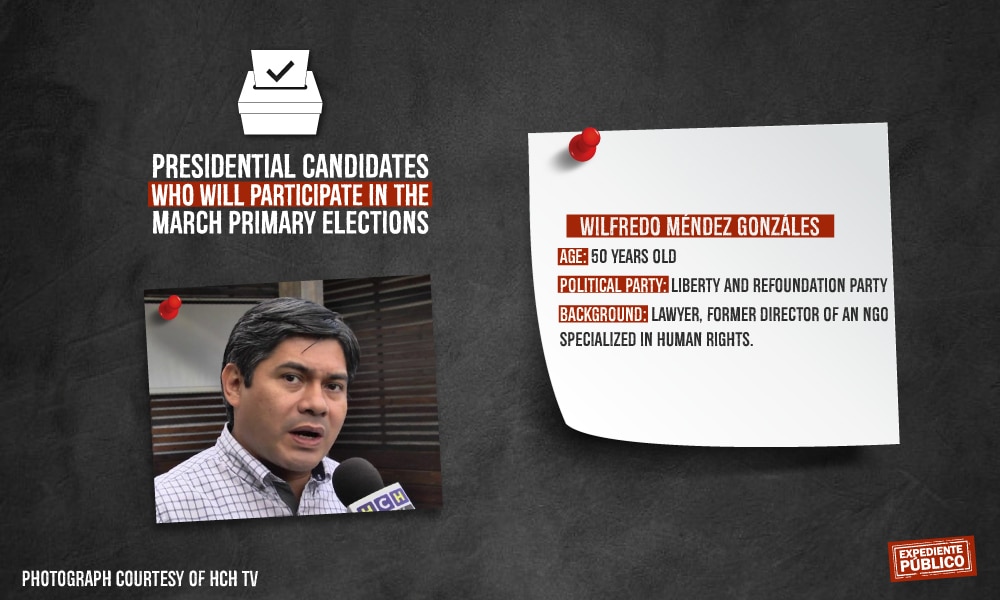

Only three of the 14 political parties who have legally registered for the November elections will participate in March. These parties, along with their political movements are the National Party’s two movements, the Liberal Party’s three movements, and nine movements of the Liberty and Refoundation Party (Libre).

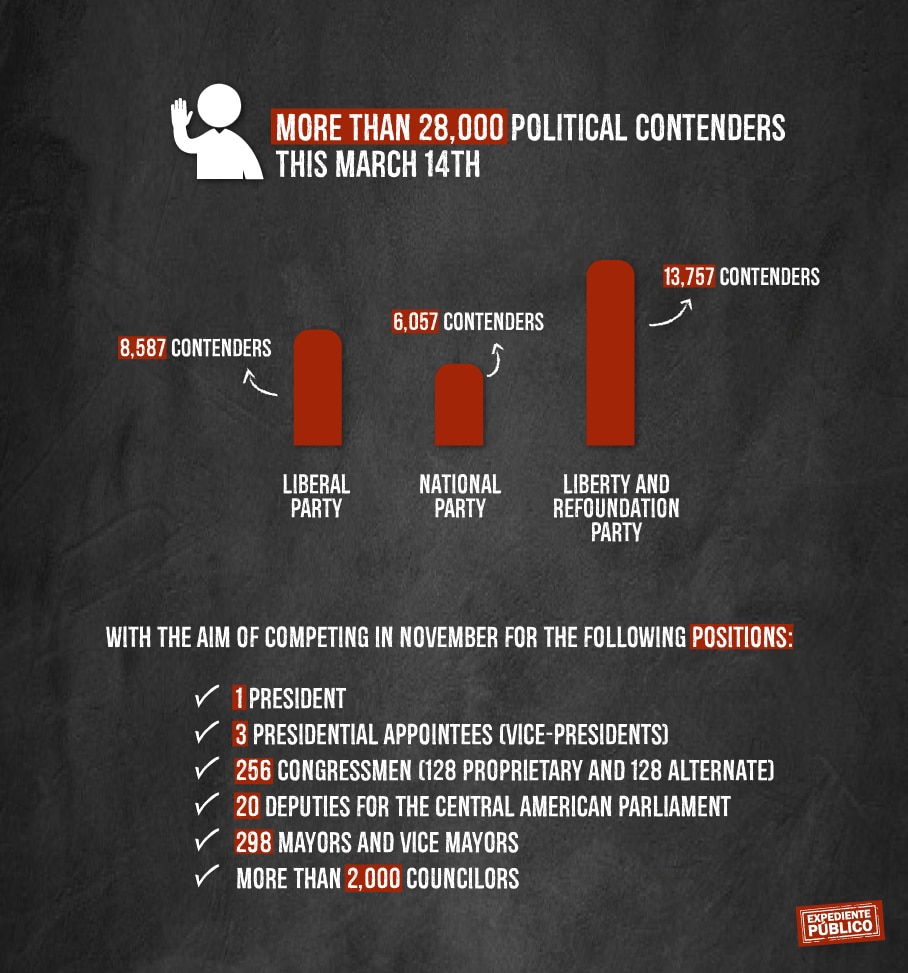

In total, more than 28 thousand aspiring politicians will participate in the elections on March 14. The Liberal Party reports 8,587 candidates, the National Party presents 6,507 candidates, and the Libre Party registers 13,757 hopefuls. The objective is to compete in November for the following positions: one president, three ministers with designated presidential functions (vice presidents), 256 national congressmen (128 proprietary and 128 alternates), 20 congressmen to the Central American Parliament, and 298 mayors and deputy mayors, in addition to a little over two thousand city council members.

In order to choose the country’s leaders in March, the three parties will vote using a fourth ballot box placed at each polling station. In general, the political movements that win presidential candidacies tend to monopolize the leadership of their parties. But, in order to win, the candidates require support from all movements within their parties, even those that they defeated in the primaries. In this respect, the ability of the movements to negotiate will depend to a great extent on the votes they receive on March 14.

For the election of these authorities, it is not necessary for each party movement to present its own candidates. Of the nine internal splits within the Libre Party, eight movements coincide with the re-election of Manuel Zelaya Rosales as its General Coordinator. In turn, he will only face the candidacy of former national police officer, María Luisa Borjas.

The 11 political parties that will not participate in March are authorized by the Electoral Law to select candidates through assembly meetings. This is because of their small memberships and lack of internal fractions capable of complying with the legal requirements to run. One of these parties, the Innovation and Social Democratic Unity Party (PINU-SD), was the first to do this last December, electing Doris Gutiérrez as its presidential candidate, the party’s only representative before the National Congress.

More on corruption in Honduras: Corruption and Coronavirus in Honduras: The Most Lethal Viruses

Background

The practice of holding primary elections began in 1989 in an effort by the Liberal and National parties to avoid splitting their ranks. Cleverly, the parties’ leaders sought to institutionalize internal discrepancies to avoid permanent divisions. Of course, these divisions later occurred in 2009 when the Liberal Party split in two as a result of its participation in the coup d’état against Zelaya Rosales, enabling the emergence of the Libre Party.

Since 1989, the consolidation process of the primaries has progressed yet developed at different speeds among political organizations. The first party to elect its presidential candidate in consultation with its electorate was the Liberal Party in 1993. Four years later, the National Party adopted this same method.

Subsequently, the consolidation of the separate ballot system with photographs of the candidates at the executive, legislative, and municipal levels occurred. Today, the existence of separate ballots allows for cross voting between political divides within the same parties. However, this cross voting is not permitted between parties, a practice that is allowed in the general elections.

The primary elections currently deploy means and resources similar to those of the general elections. For March, the National Electoral Council (CNE) has a fiscal baseline of 1.2 billion lempiras (50 million dollars), a figure comparable to the 1.8 billion lempiras (72 million dollars) spent ahead of the 2017 general elections.

«The primaries should be managed and financed directly by the political parties, with the CNE present as supervisor. It should not be possible to spend the same amount of money in the primaries as in the general elections», says congresswoman Gutiérrez.

Campaign Spending

In 2016, the country approved the Clean Politics Law (Ley de Política Limpia) to oversee political parties and their candidates. The Clean Politics Law was one of the initiatives promoted by the now defunct Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH). MACCIH was overturned by the legislative branch, limiting many of its functions, including its founding purpose, which was to follow the money.

The Auditing Unit, in charge of ensuring compliance of said law, «is managed by the three major parties (National, Liberal, and Libre) and is highly politicized in order to maintain information regarding campaign expenditures a secret», explains Gutiérrez.

However, it is estimated that campaign spending ahead of the primaries varies according to each politician, along with the party and political movement that he or she represents. Additionally, the candidate’s status as incumbent or challenger comes into play, as well as the sector from which his or her campaign benefits.

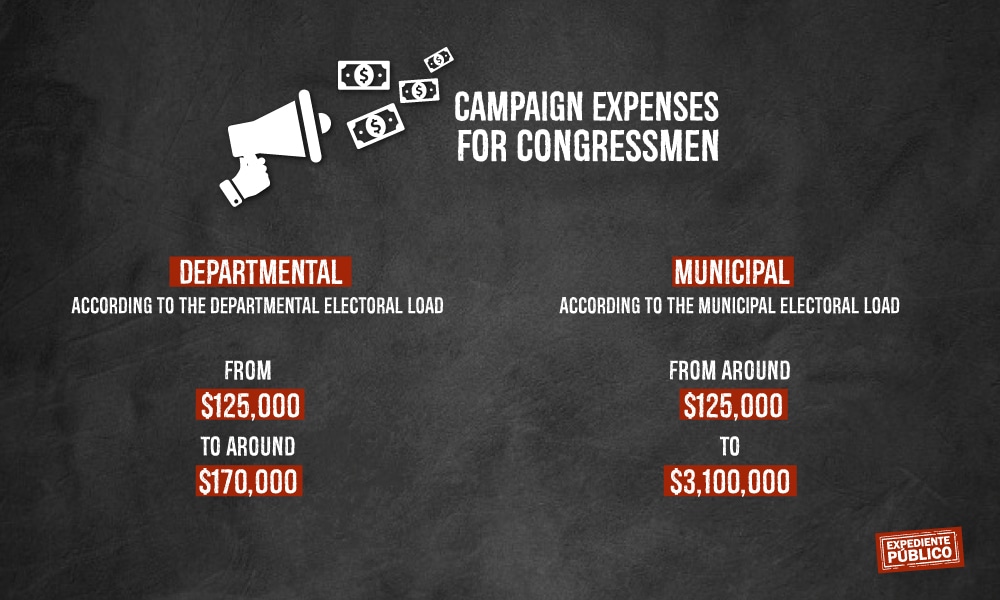

Limits to campaign spending for the primary elections have already been authorized by the CNE, with the established ceiling applying to the November general elections as well. At the presidential level, a candidate is authorized to spend up to 544.2 million lempiras, which is equivalent to approximately 22 million dollars.

At the legislative level, the amounts shift according to the electoral burden of the departments and range from three million lempiras, about 125 thousand dollars, to four million lempiras, around 170 thousand dollars. Meanwhile, at the municipal level, permitted expenditures start at three million lempiras, a little more than 125 thousand dollars, and reach 76 million lempiras, around 3.1 million dollars.

Nevertheless, ahead of the March 14 elections, many politicians already seem to be on their way to the general elections, having deployed large amounts of vehicles, paid political activists, and invested extensively in publicity campaigns on social media and in the news.

«Someone that spends a great deal on his or her campaign clearly does so because he or she will later receive some sort of renumeration, as in business. Within the Liberal Party, there are some movements whose candidate lists are marked by those who would do Honduras a favor by stepping aside», comments Karla Medal. Medal, a 27-year-old woman, is running for re-election as an alternate representing the movement, “The Hope of Honduras” of Darío Banegas’ Liberal Party in Congress.

According to Medal, the Liberal Party has not supported her campaign expenditures, claiming to have financed her campaign through personal contributions, family, and friends. «The movement of the party’s president (Luis Zelaya) is that which has access to the public debt. In theory, this money would be divided up between different political movements, but in practice this is not the case», Medal comments.

«We compete with people who are packing suitcases of money right now to go buy off those whom we tried to convince to vote for us voluntarily. It is difficult to get to a place where, in order for people to work for you, the first thing requested of you is money», expressed Pili López, another Liberal candidate running for the National Congress representing the department of Francisco Morazán, to Expediente Público.

López comments that she has invested very little in publicity for her campaign but is conscientious that she will have to undergo more expenditures ahead of March 14. «How does one have volunteers at polling sites without food or transportation services? Why would volunteers alert us to potential discrepancies if we aren’t providing them credit for cell phone use?», she asks.

Pili López says to have opened a ‘clean’ account for political contributions where she deposits money that she receives from a range of activities, including t-shirts sales to sponsor those that will watch her votes come in at polling sites.

Fraud around the corner?

Because of the country’s track record, this year’s primaries begin with increasingly low credibility. Counselor representing the Libre Party before the CNE, Rixi Moncada expressed her fear of electoral fraud in the March and November elections.

Since 2019, the three major parties have divided up the seats on the CNE Board of Directors. However, the councilors have been in constant disputes, to the point that Moncada alerted, three weeks before the elections, that the electoral body was experiencing a «serious internal crisis», pointing out that the Nationalists were impeding decisions in favor of electoral transparency.

Riki Moncada’s suspicions respond to the three parties’ inability to agree on four points: updating the electoral census, the management of voter credentials at the 23,880 polling sites, the vote-counting method, and the monitoring and overhaul of vote counting.

It is clear that Honduran authorities did not properly fulfill their democratic duties. In the first place, the National Congress did not approve the new Electoral Law, causing a legal vacuum in the meantime. Moreover, the National Registry of Persons (RNP) did not finish purging the national electoral census, probably excluding 1.5 million voters. The CNE also failed to reach an agreement on the use of voter credentials and did not unify the methods by which parties count votes. All in all, these are the reasons that Moncada fears electoral fraud.

Read more: “Honduras in search of justice”

«We are facing a very sui generis legal situation because of the lack of a new Electoral Law both in the CNE and in the Electoral Justice Tribunal (TJE), generating ambivalence and uncertainty. Now, it seems parties may count [votes] how they please. One of the parties gave the names of those who went to the polling sites, while others did not. People will also be voting using old and new cards, which makes it possible for a person to vote more than once», explains Doris Gutiérrez, who considers that «fraud is just around the corner».

The lack of confidence comes from practically all sectors of society, including the candidates themselves. «How can I trust the electoral system if, 10 days before the elections, the new Electoral Law has still not been approved and there are still doubts regarding the administration of voter credentials?», asks candidate Karla Medal.

For the public, the lack of credibility in the process has to do with the composition of the CNE, integrated by councilmen who are active members of the Libre, Liberal, and National parties. Although voices such as Moncada’s oppose the government, all members are accused, without exception, of acting in the interests of their political parties and not of democracy in general.

According to the latest perception survey carried out by the Reflection, Research, and Communication Group (ERIC-SJ), 81.8% of the Honduran population does not trust electoral institutions. Undoubtedly, this is one of the reasons that 42.4% of citizens abstained from voting in the most recent elections of 2017.

In this sense, the primaries expose the weaknesses in the electoral system and institutions, which do not have sufficient legal tools nor the will and resolve to guarantee the legitimacy of election results.

While the transparency of the vote remains in question, the same is not true of its usefulness, which allows different groups to ascend to positions of power. In this way, organized crime and proponents of the extractive industry have aspired, in each electoral process, to achieve greater political representation in the places where they operate.

Allegations of politicians who are tied to drug trafficking yet seek nominations from their political parties are frequent, beginning with President Hernández’s connections to drug trafficking, which he supposedly used to gain power.

While there are accusations of the three major political parties’ being linked to organized crime, allegations are more frequently made regarding the National Party. It is worth pointing out that the brother of the current president and the son of former Nationalist President Porfirio Lobo Sosa are in United States federal prison for drug trafficking.

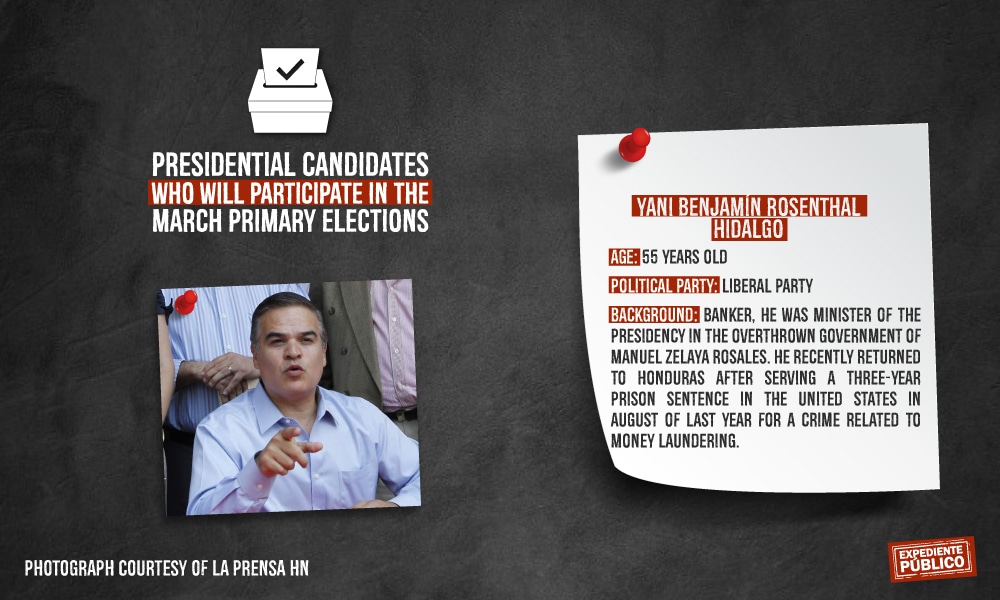

As far as the Liberal Party is concerned, Yani Rosenthal propelled himself into the electoral arena after returning last August from a New York prison where he spent three years on money laundering-related crimes. These are only the most representative and evident cases.

Conservatism and electoral discrimination

For the Honduran electorate, political party options are seemingly too wide. However, the options for political wins are limited to the three major parties and the Salvador de Honduras Party led by Salvador Nasralla; the rest of the parties do not come into play. In terms of ideological differences, right-wing conservatism and left-wing populism prevail.

The scarcity of ideological options is made worse by the electoral discrimination of vulnerable groups: women, young people, indigenous persons, African Hondurans, LGBTI members, and those with disabilities.

In the case of women, in addition to having less resources for their campaigns, the formula established to regulate the application of the parity principle and the alternation mechanism in political participation is mandatory, according to the electoral burden, in the third, fourth, and fifth spots of candidate lists.

Thus, it is not strange that political participation in the general elections of 2017 for congressional candidates was composed of 568 women (44%) and 711 men (56%). However, of the 128 seats available for congressmen, only 27 women were elected (21.9%), a percentage that represents a setback compared to the 33 women elected to the National Congress in 2013 (25.7%). Moreover, none of the current congresswomen preside over any legislative committee.

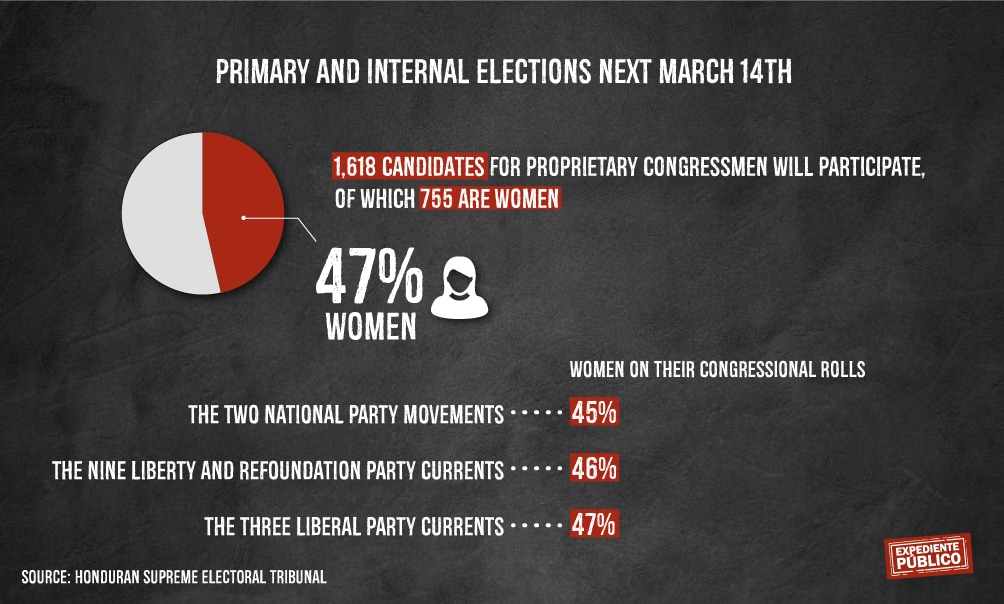

755 of the 1,618 congressional candidates (excluding substitutes) that will participate in the March 14 primaries are women, the equivalent of 47%. Regarding the parties’ congressional candidates, women represent 45% of candidates for the National Party’s two movements, 46% of candidates for Libre’s nine movements, and 47% of candidates for the Liberal Party’s three movements.

If the inclusion of females in electoral politics is difficult to achieve, the LGBTI community struggles even more because of the discriminatory nature and traditional intolerance of legislation. Their leaders, who are not recognized as having any other identity aside from that of which they were given at birth, have to face daily aggressions by individuals and police, illegal detentions, and constant incidents of sexual abuse and rape.

The media’s silence around their aspirations for public office is absolute, to the extent that community members seem inexistant. Ahead of the primaries, there have been no reports of any LGBTI activist declaring candidacy for any of the three major political parties. However, since 2012, several community members have run for public office.

«Their political participation as candidates has been a huge advance in rejecting our current reality», comments Michelle of the Cozumel Trans Network to Expediente Público.

This electoral participation is not an exception to the permanent risks that the community faces. In 2012, gay rights activist Erick Martínez Ávila was murdered the same year he appeared as candidate for the Libre Party in the primary elections.

Despite the risks, three representatives of the LGBTI community made the list of candidates for the National Congress in the November 2017 general elections: Rihanna Ferrera of the Cozumel Trans Network, David Valle of Somos CDC, and Ivan Banegas of Colectivo Violeta.

Of the three, only Rihanna made it to the general elections. Rihanna is a trans woman who was obligated by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) to use her birth name, the same name that she had not employed socially in over a decade. Even so, she maintained more than 15 thousand votes in her favor.

«I campaigned while I studied and worked, investing 22 thousand lempiras (800 dollars) from my own wallet. Throughout the process, I received threats, was run over by a car, and had two motorcycle pursuits…I even received a message that I was “on the list”», recalls Rihanna Ferrera.

The indigenous and Afro-descendant populations, which represent 7.25% of the little over 9.5 million people living in Honduras, suffer from a similar situation of harassment with an even greater number of victims. The community is only represented by three of its members in the National Congress, which is composed of 128 congressmen.

In its final report on election monitoring in Honduras in 2017, the Coalition for Non-Partisan Electoral Observation (ON-26) stressed that the «practice of discrimination is still present in the Honduran electoral system, making a person feel excluded from the democratic system».

To guarantee vulnerable groups’ right to participate in politics, the communities’ most representative organizations demand that proper legal reforms take place, even though political parties ultimately have the last word.

In the four decades since the return to constitutional order in 1980-1982, the most significant transformation of the Honduran political system has been its move from an old bipartisan system to a multiparty electoral democracy. However, the evolution of Honduras’ political culture, continuously controlled by elites, authoritarianism, and dogmatism, did not have the same fortune.

Predictions ahead of March

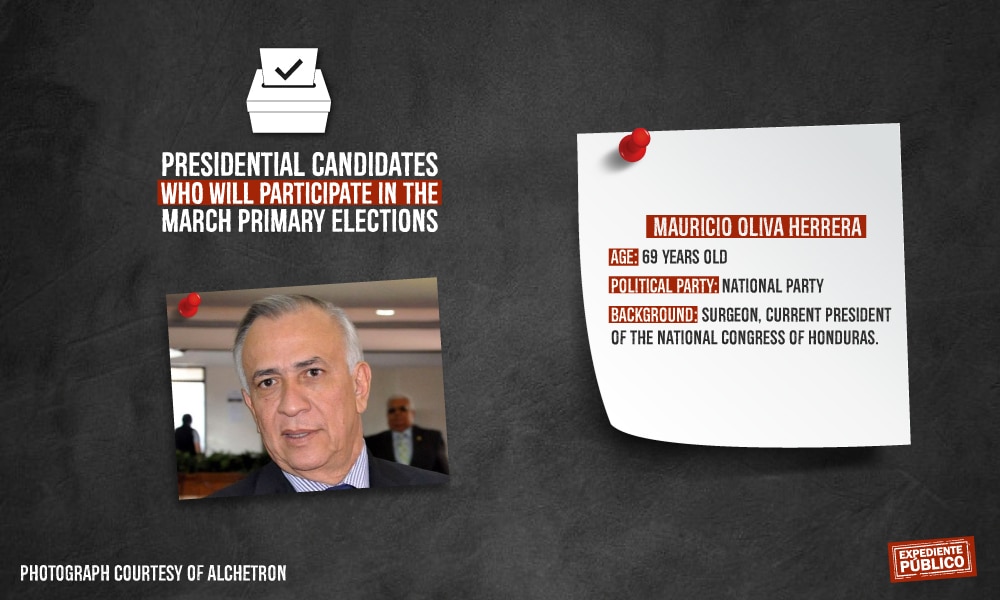

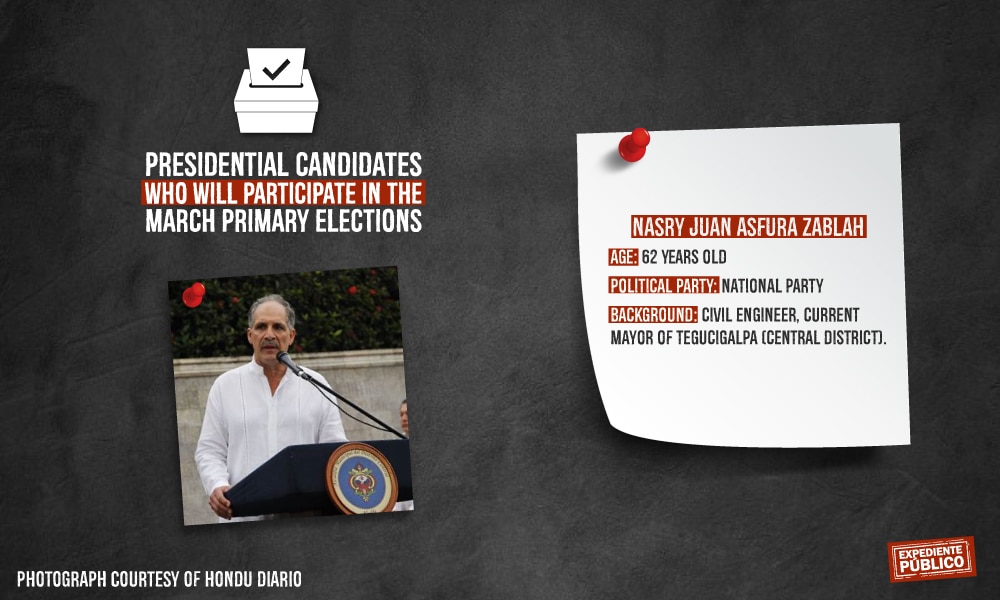

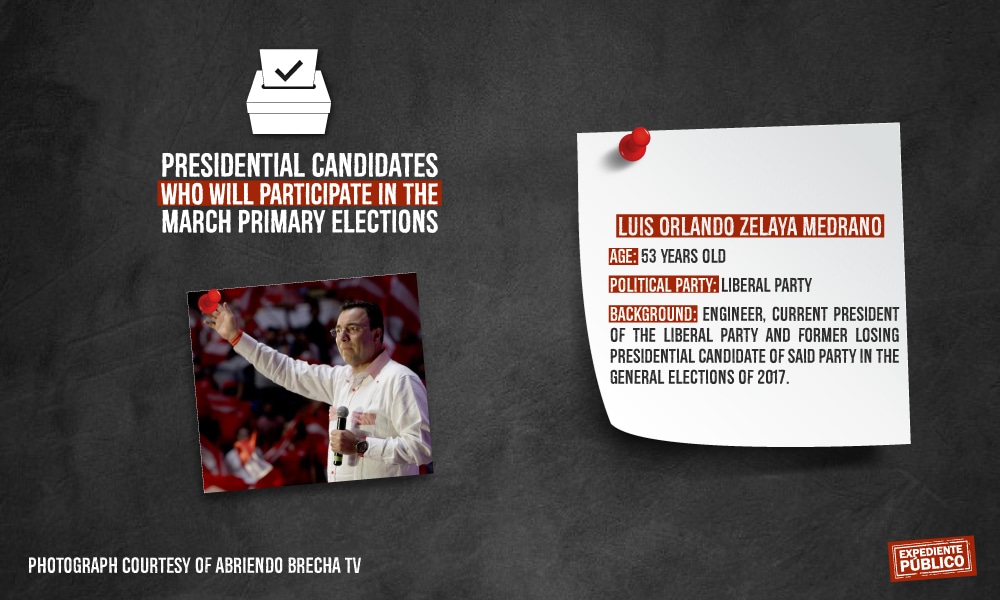

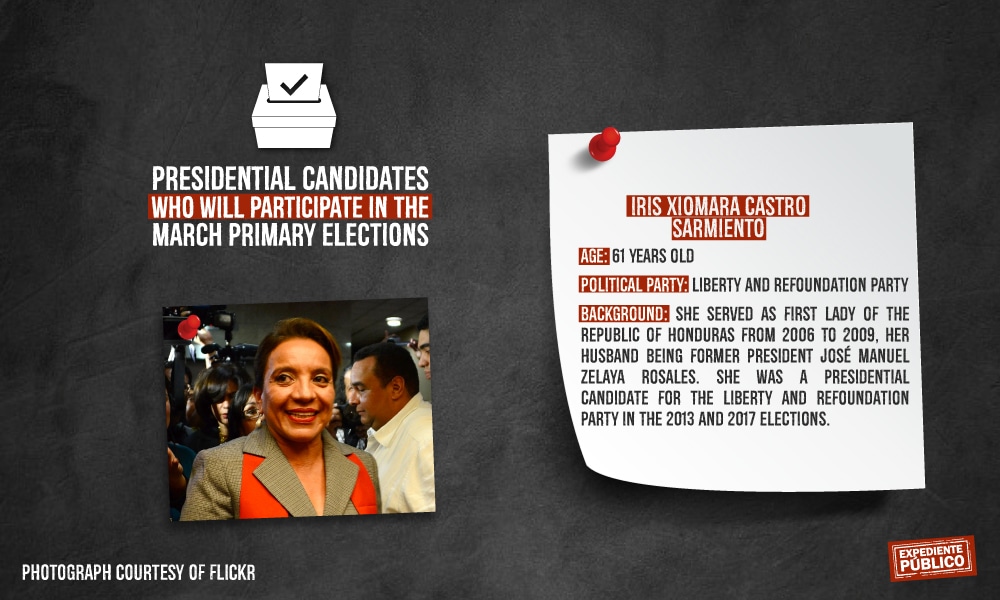

Within the Libre Party, it is clear that the presidential ticket will be won by Xiomara Castro. However, regarding the Nationalists and Liberals, the presidential candidacy is still a toss-up. For example, within the ruling National Party, Mauricio Oliva, head of the National Congress and Nasry Asfura, mayor of the capital city have the political machines with the public resources necessary to fund their campaigns. The two are more or less evenly matched in this sense. There is uncertainty, however, regarding President Hernández’s nod, which looms over both Nationalists. While Hernández has not fixated on either candidate, support from his inner circle has been for Asfura.

The number of incumbents in Congress who support Asfura, along with other ministers of government, and aspire to re-election totals to 43. For Olivia, there are only 16. Despite this, on the eve of the elections, the competition is somewhat close. Both presidential hopefuls will have to negotiate later to avoid dividing their party in light of an electoral win.

Among the ranks of the Liberal Party, Luis Zelaya and Yani Rosenthal are central protagonists. In their case, the winner will take all. Because of the tone of their political discourse, there will be no space for compromises. «I win and you leave» seems to be the exchange between the two candidates.

Overall, the «bonsai» or «briefcase» parties, as minority parties are often called, aspire only to maintain their legal registration and avoid the slightest chance of surprise, with the exception of Salvador de Honduras led by TV presenter Salvador Nasralla.

In fact, Salvador Nasralla is no longer a rookie in the race, neither by age (68) nor by electoral experience. The 2021 election will be his third incursion into the electoral arena. In the 2013 elections, he headed the Anti-Corruption Party (PAC) and received 418 thousand votes (13.43% of total votes). Four years later, he came close to victory, receiving 1.3 million votes (41.42% of total votes) yet losing by a few votes to Hernández in an election described by the Opposition and some international organizations as «fraudulent».

What does remain clear, however, is that while political parties carry out their electoral spectacle, the country finds itself in the midst of an unprecedented economic, social, and health crisis. Most citizens are not at all interested in preparing to vote on March 14. The real challenge is surviving, and, if survival is not possible inside the country, then they emigrate, which is the reason why Hondurans have patented «migrant caravans». In fact, it is estimated that one million Hondurans are living abroad. That same million still appears in the electoral census, as do Covid-19 victims.