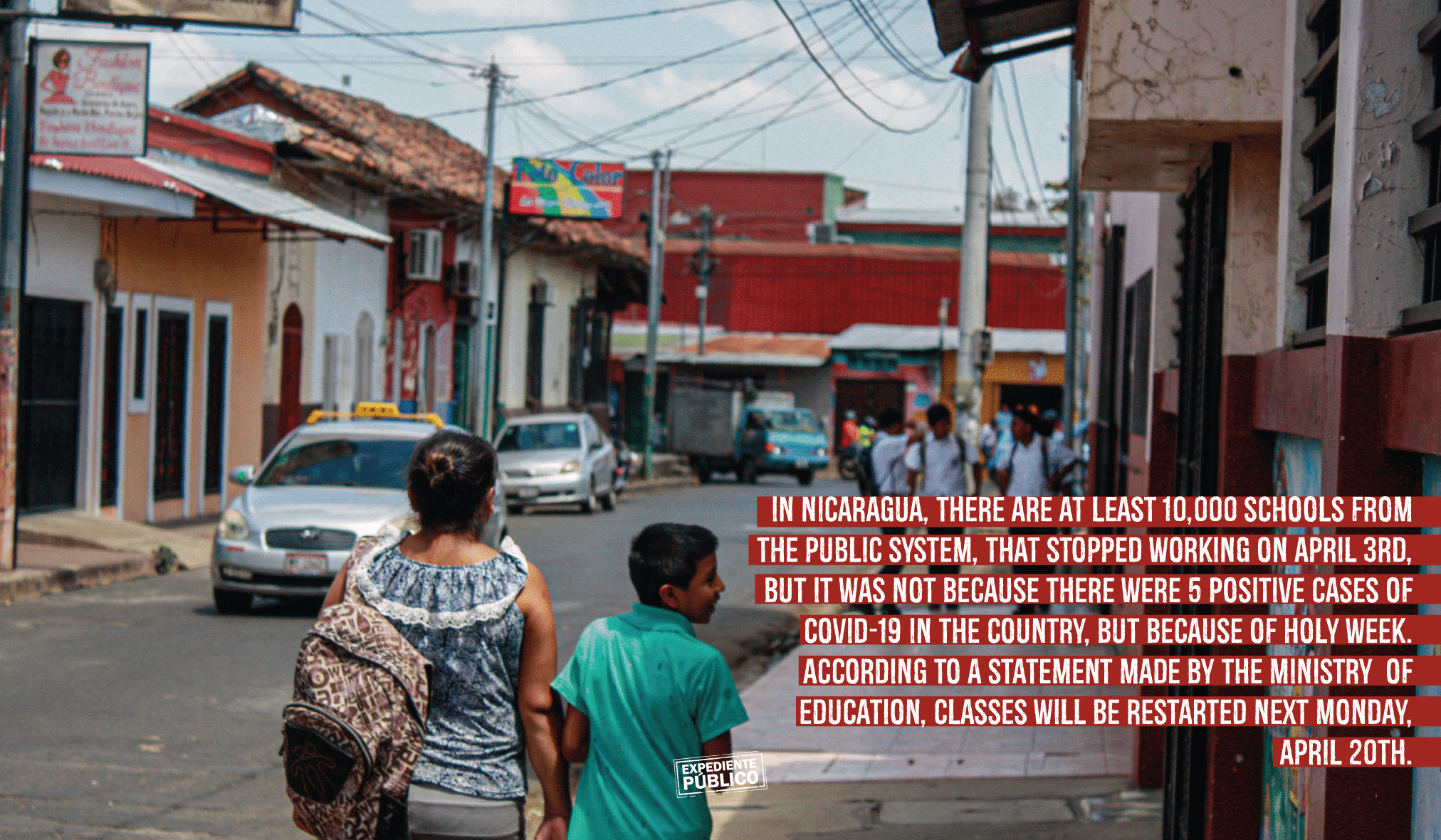

Masaya, 26 kilometers southeast of Managua, Nicaragua’s capital, March 31: while a large part of the world’s schools have orders to keep their students at home due to the COVID-10 pandemic, in this and all other cities of Nicaragua, groups of students sit on one of so many black-painted benches in the central park after leaving class, where they discuss their exams. They can’t stop attending school because the regime of President Daniel Ortega and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo, have threatened them with losing the school year if they stay home.

-Our parents tell us not to go to classes because we’re going to get sick, says a young redheaded girl in the group.

-If we don’t take the exams we won’t pass the year, she adds, passing her hand over her eyes then her nose.

-The use of masks and gloves is prohibited, adds another young man who is wearing the uniform of the Dr. Carlos Vega Bolaños Central Institute.

The regime has reiterated that it will keep people working to maintain the economy, but in the case of the students and teachers, opponents can only speculate that the government wants to keep them active to use them as it does with all other public employees, in its political agitation campaigns, as Civic Alliance representative José Pallais, told Expediente Público.

COVID-19: the Ortega-Murillo regime’s reckless gamble

Disinformation about the seriousness of the coronavirus reigns in the public centers, thus leaving the students exposed, but this isn’t the only or even worst problem, as the Government of Nicaragua has also not taken seriously the students’ safety and has turned a deaf ear to the measures recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

“We’re suffering a world health crisis,”, comments a mother who lives in a community at kilometer 14 of the highway that connects Managua to Masaya. She decided to stop sending her son to public preschool to avoid exposing either him or his family: and his friends aren’t going to class either.

-What’s the point of taking him to school and picking him up if I’m only exposing him, myself or his dad? ⸻ she says.

The teachers are being required to go to work.

-There’s very little attendance in the school, and I’m not sending my daughter, because there’s no water for washing their hands and I think it’s a risk for her even though the teachers say they should go to class, said a father from the community of Tola, in the department of Rivas, 114 kilometers from Managua.

Fear of exposing their children to a pandemic that has paralyzed the economy of far richer counties is the feeling of all those consulted by Expediente Público, but neither the Government nor the Education Ministry (Mined) has taken action.

The situation of the public schools in the “pueblos blancos”

The first case of coronavirus in Nicaragua was “officially” confirmed the night of March 18, when the clock struck 8:00 p.m., and from that moment forward, the communiques cancelling physical class attendance of the country’s private schools began to quickly pile up. Nonetheless, it was precisely the opposite in the public schools. They all continued requiring in-person attendance.

Preschool, primary and secondary enrollment in Nicaragua is roughly 1.8 million, 85% of which corresponds to public schools while the remaining 15% is private, according to Mined data.

The regime’s most publicized measure against the pandemic has been an educational campaign promoting hygiene, mainly washing one’s hands with soap, but many students attend schools where there is not even drinkable water, much less soap.

Data form the Nicaraguan Coordinating Body of NGOs that Work with Children and Adolescents (Codeni) indicates a lack of water supply in 5,000 schools, in other words half of the public educational centers considering that there are 10,000 in the country, which makes the hygiene and health conditions even more complex.

Codeni favors the suspension of classes and the restructuring of the academic calendar given the pandemic, not only to protect all the students but also the 53,000 teachers and their families.

“In past situations of catastrophe or emergency, classes have been suspended and school calendars adjusted to correct for the interruption of classes,” pointed out the coordinator in a press statement on March 19.

The Institute of San Juan de Oriente, 45 kilometers south of Managua, has two washbowls for more than 300 students, but only the one near the entrance is working. Before this year’s Holy Week vacation of April 14-19, one bar of soap typically used for washing clothes was placed there to supply all the students and teachers of the morning and afternoon sessions.

-Now they put soap where we drink water, said one of the students sitting on a corner of the school’s stage, and added:

-If this illness comes here to our municipality, everyone is going to be in quarantine, but hopefully it won’t come.

The Benito Juárez primary school and the Agusto C. Sandino Public Institute of Niquinohomo, the Benjamín Zeledón Institute of Catarina, and the República Alemana and Jesús el Buen Maestro schools of San Juan de Oriente, all towns known as the “pueblos blancos” (white towns) of the department of Masaya, bordering the department of Managua, kept their classes open until April 13, the last day before Holy Week, although the absence of students was notable.

Claudia has her three children enrolled in public schools of San Juan de Oriente, but decided to stop sending them to class.

-I wouldn’t like them to lose the school year, but nor would I like them to get sick, and sending them to class exposes them. The government hasn’t suspended (classes).

What can be done?

Josefina Vijil, who has a doctorate in Education Sciences, says that one of the most urgent measures in the framework of this pandemic is to close the schools because it’s the only way to protect the population’s most vulnerable people. “It’s not that we want to close the schools but that we need to do so to avoid the propagation of the virus,” explained the expert.

Some of the other measures Vijil suggests are:

- Take advantage of the experience he private schools already have, their methodologies, class plans and didactic proposals for on-line formats that can be shared with the State.

- Insofar as possible, use cell phones for didactic activities. The government could subsidize Internet access to certain families as it did for years, offering internet free in the central parks.

- Use television and radio as educational platforms for children who don’t have access to computers or cell phones, as is being done in other countries.

Vijil admits that all these platforms aren’t exactly ideal, but area a way to mitigate the need to close classes for a while. “When we return to classes, other measures will have to be taken as reinforcement, probably extending the school year, which is what many other countries are going to do. In any event, there are many ways and proposals.”

The Multidisciplinary Scientific Committee of Nicaragua, an independent group of experts in different disciplines, including the area of Health, consulted various teachers for some proposals about the educational emergency in Nicaragua and they are now available to the Government, but for political reasons it has not implemented them.

Measures taken in private schools

In neighboring nations like Honduras Costa Rica and El Salvador, the authorities have taken into account the measures suggested by WHO, canceling classes including in the universities, suspending massive events and recommending frequent hand-washing, not greeting people with hugs and kisses, and not leaving home.

In Nicaragua, many private schools have opted to cancel on-site classes, such as Fe y Alegría’s Inmaculada Concepción School in the municipality of Ocotal, 24 kilometers from the Honduran border, which before closing its on-site classes published in its Facebook page recommendations for preventing respiratory diseases.

At least four private schools in the city of Masaya suspended on-site classes and are making use of technological tools to send assignments to primary students by WhatsApp and their parents come to leave the homework at the school. The teens in secondary school use the platform with more skill, according to a collaborator of the Nuestra Señora del Pilar School.

“The parents’ board of the school presented a letter to the Ministry of Education requesting that classes be taken on line, and we’ve been working that way ever since,” she explained.

“It’s the second time we’ve worked this way,” commented another collaborator at the Carlos Vega Bolaños school, recalling that during the 2018 protests they had to implement this same dynamic, and this year, given the world emergency, the parents decided not to send the kids to class and they have that right and duty,” she added.

The schools consulted by Expediente Público in the department of Masaya that are using virtual classes are the Salesian Don Bosco, the Baptist of Masaya, the Baptist El Alfarero, the Baptist Faro de Luz, the Niño Jesús Colegio and the Santa María Academy.

Although weekly attendance in this last educational center does not exceed 10 students in all grades, the director commented that they have not canceled on-site classes, but “the parents made the decision; they are afraid to send their children even though we gave them the measures.”

Students at public schools in Matagalpa and Jinotega also abandoned the classrooms

“I prefer losing the year to losing my life,” said don Nemesio Pérez, who decided not to send his 9-year-old grandson Tony to public school in Matagalpa City 130 kilometers northeast of the capital. As a result Tony receives his homework from his teacher on WhatsApp every day and sends it back to her done.

In the departmental capitals of both Matagalpa and Jinotega, class attendance in some primary and secondary public schools is scant; out of groups of 30-45 students only 3-10 attend class, according to a pulse-taking by Expediente Público of parents in these cities.

Tony’s grandfather says the boy gets bored ad a little rebellious about doing his schoolwork at home, but he knows that this measure could save his life, given the risk of contracting COVID-19.

It appears that the decision to have classes on line has been a particular initiative of some groups of parents and teachers, and there are some who join the initiative and others who do not.

Arlen Tinoco, a mother, says the teachers told her that Mined wasn’t allowing this alternative o class attendance because it is very costly for families that don’t have access to technology.

In other schools, like the Pablo Cuadra primary school of Matagalpa, the issue of sending homework via WhatsApp has not been an option, so the parents are taking workbooks to the school to receive and deliver their children’s homework. Nonetheless, says Tinoco, some parents haven’t even shown up to the school to turn the workbooks in to the teacher.

On the other hand, there are schools like the Eliseo Picado National Institute, a secondary school, where between 10 and 15 students still come as a group, says Nidia Moreno, the mother of a 13-year-old boy.

Nidia thinks the fact that so many students go to receive classes could jeopardize those not being permitted by their parents to attend the institute. Some teachers of Nydia’s son have said that the students who miss the evaluations and exams could lose the school year.

This situation worries Nydia, but the decision to save her son from imminent contagion is firm. A year can be recovered, she insists, but the life of a son is irreplaceable.

Will they lose the school year?

Auxiliadora Herrera, a teacher in a public primary school in the department of Jinotega, 142 kilometers northeast of Managua, doesn’t think the parents should be so concerned; that the children won’t lose the year and alternatives may possibly be sought so this doesn’t happen.

In Herrera’s group no child has come to class since the Government announced the first case of coronavirus on March 18. Although the Government has not announced a contingency plan to avoid contagion, Herrera says that Mined has provided health workshops on avoiding propagation of epidemics, among them COVID-19 and dengue. They are recommending the constant washing of hands, but have not recommended the use of masks in the classrooms.

The teachers are also afraid

Azucena Zeledón, a primary school eater in Jinotega, says she experiences fear of catching the coronavirus, but has to continue showing up at school, even if the children don’t.

Mined is not indicating how to conduct Nicaragua’s education given the coronavirus emergency, which is keeping children, teens, teachers and parents all in an ongoing climate of uncertainty. The teacher Zeledón concludes that she has no better alternative other than to deposit her trust in God’s hands.