* The pioneering organization in the search for children abducted by the army in the 1980s continues to face a lack of interest from the government in power.

** The authoritarian government of President Nayib Bukele weakens the institutions created to clarify the truth about minors who have been abducted and given up for adoption irregularly.

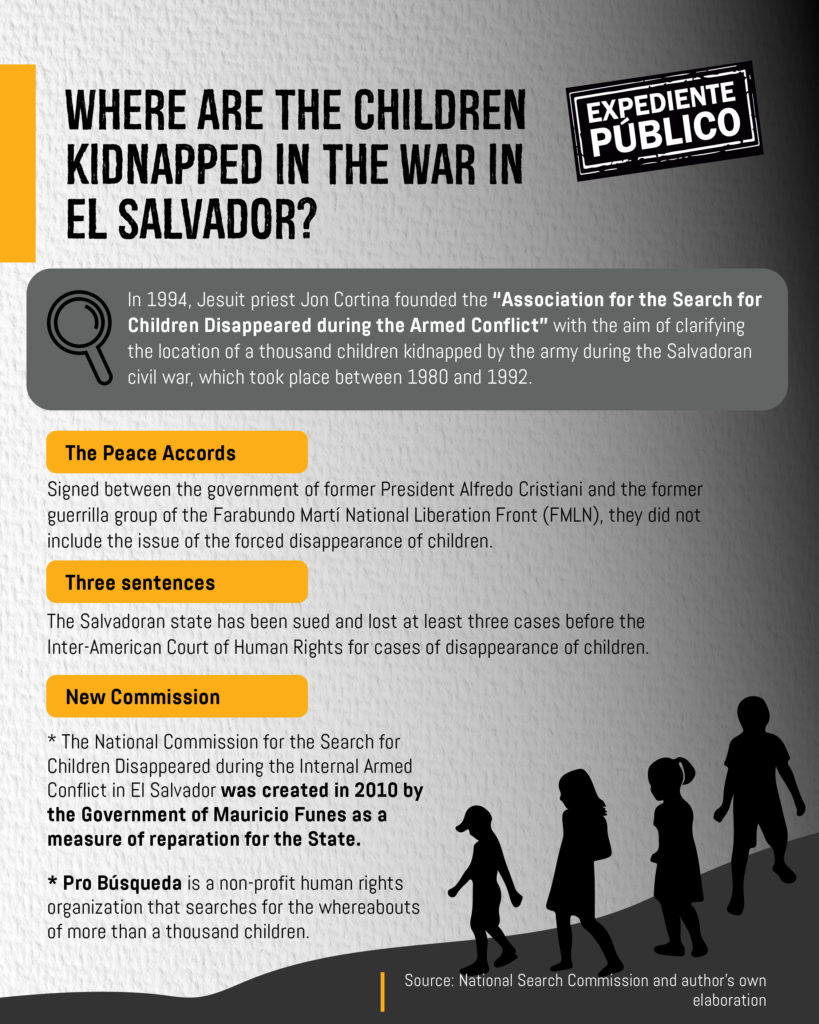

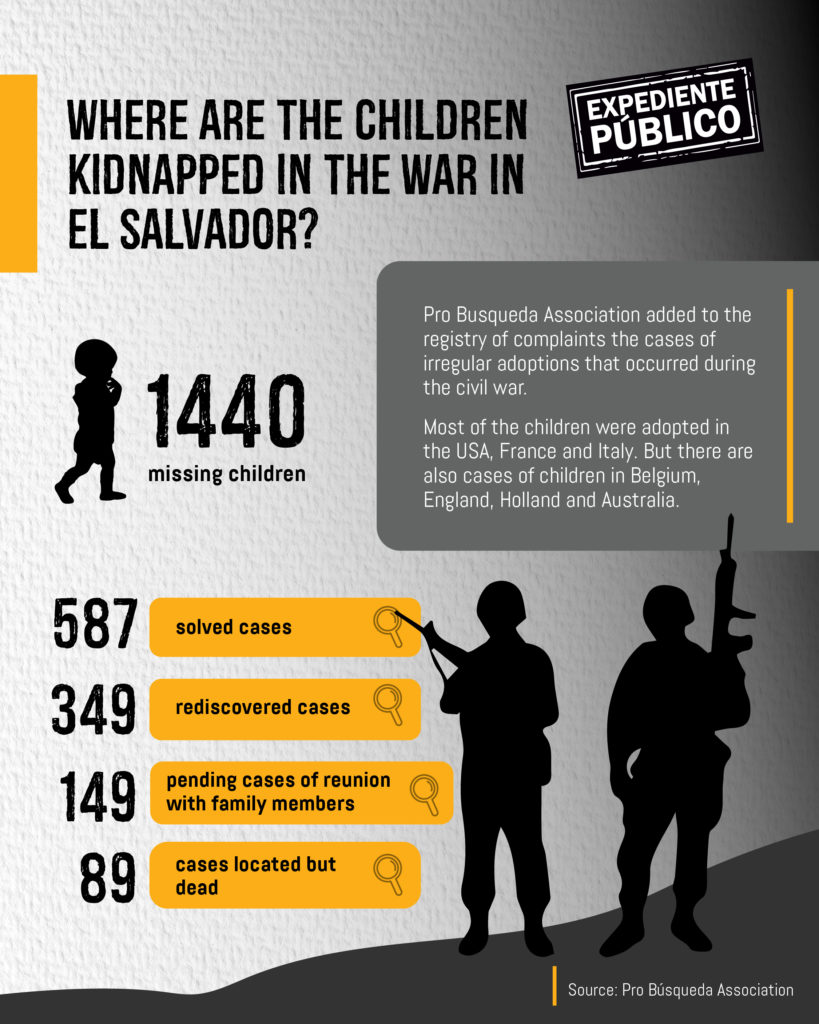

*** The Pro Search Association, which was born in 1994 on the initiative of Jesuit priest Jon Cortina, totals 1,440 cases to date.

Eric Lemus / Expediente Público

The reunion of children kidnapped by the Armed Forces is one of the episodes that continues to be officially denied, even though the Salvadoran State was condemned in 2005, 2011, and 2014 by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (I/A Court H.R., or Corte IDH) for three cases of forced disappearance.

Although the government of former President Mauricio Funes created the National Commission for the Search for Children Disappeared during El Salvador’s Internal Armed Conflict in 2010 as a measure to compensate for state responsibility, the search for information on military operations continued to be adverse under his administration and continues to this day.

In fact, President Nayib Bukele, who will seek re-election in 2024 in this Central American country, increased the blockade of military archives when a judge inquired about the participation of the military in the massacre of a thousand peasants in the village of El Mozote, in the department of Morazán, in December 1981.

Subscribe to the Public Records newsletter and receive more information

Among the victims are sisters Ana Julia and Carmelina Mejía Ramírez, 15 and seven years old, respectively, who initially survived the massacre but were later recaptured by soldiers from the Atlacatl battalion and have been missing ever since.

Enforced disappearance of children in El Mozote

Ana Julia Escalante, executive director of the Pro Search Association, tells Expediente Público that it is one of the few examples where victims survived, but their traces vanished.

“There is testimony of a person who saw that the girls were taken and given to a person in a house, they have them in that house; but then the army arrives and takes them away again,” says Escalante.

“From that moment on, nothing is known about the whereabouts of the two girls. In this case, we will continue to accompany the family,” says the director of the organization.

Read: Massacre en El Mozote: 41 years without justice for the 978 Salvadoran victims

The case of the Mejía Ramírez sisters was reported in November 2001 to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the case is still open at the regional level.

“There are cases that are linked to the armed conflict, in which families have filed complaints; but applications from people adopted abroad (…) in that period of the conflict are also incorporated,” Escalante details.

Claims that don’t stop

The increase in requests for technical assistance is an open tap in which situations increase, especially because of the adoptions made in those years. It’s like a spring jumps automatically when you hear the story.

“Because of the contexts of the stories – because a prior interview is always done – it is determined that they are linked to the conditions of war, of children who were given up for adoption in irregular conditions,” she explains.

Throughout these three decades, one of the stumbling blocks faced in this work is the lack of information on military operations and the reception abroad of children from El Salvador.

Researcher Leila Juzam, who was at the Center for Human Rights at the University of California, Berkeley, for example, analyzed the factor of an under-registration of people adopted during the conflict who have had no contact with either Pro Búsqueda or the CNB.

“It is enough to pay attention to the figure that the press in the U.S. handles the number of adoption visas granted: 2,354 of them by the State Department of the Federal Government to couples from that country who adopted children from El Salvador during the war years,” she said in an essay.

On the other hand, there is also the fact of those victims who do not report and continue to remain silent because of the fear that persists.

“There are two sources of information here: families and adoptees. From about six years ago to date, there has been an increase in the number of cases where adopted people are requesting” the intervention of the organization.

The normalization of impunity

Helí Hernández, a legal technician at the agency, has spent his entire career working on humanitarian work in cases of exhumations and violence against the civilian population.

“Impunity endures and the lack of commitment from the other organs of the State,” he reflects while talking to Expediente Público.

“In the case of the disappearance of children, it is clear that Salvadoran governments have avoided offering information to the families and thus end up favoring the old military guard, which indicates that they are a power to which they remain loyal,” Hernández adds.

Furthermore: Without fanfare, El Salvador celebrates 31 years since the end of the civil war

Bukele’s government, like previous administrations, restricts access to military archives that allow the location of hundreds of cases to achieve family reunification.

“Much of Salvadoran society has normalized statements such as ‘the guerrillas did not have the right to raise their children’ and that the children taken from their families were ‘better off, with good families,’” said lawyer Leonor Arteaga.

Arteaga, who is director of the Impunity and Serious Human Rights Violations Program of the Due Process of Law Foundation (DPLF), reiterates that “these beliefs are typical of guardianship where the State decides on the fate of children, especially poor children.”

The Patterns of Rapture

The case followed by the Salvadoran army has similarities with the tactics used by the Argentine dictatorship, whose practices are classified as crimes against humanity, with the exception that in this Central American country no one was tried.

Read: “The massacre”, the souls in pain who still demand justice in El Salvador

“There are quite a few routes that the children took. One was the appropriation even by people from the same army in cases such as ‘I took him to my mother because she was alone,’ or many cases of girls who were taken to domestic work, in conditions of slavery or were also subjected to sexual abuse,” says Ana Escalante.

In addition, “the purposes of the appropriations of children are several; but, above all, they were because they were considered the seed of the guerrillas and one way to destabilize the enemy was to remove that seed and somehow lower morale by appropriating the children.”

“There were cases of children who grew up under the authority of a high-ranking military officer within a detachment. They grow up with a military background and one of them even retired working there because that was the life he was taught,” he says.

“Logically, when they know what happened, they go into shock because the one who took them was practically the one who murdered their family.”

Children as spoils of war

Another pattern that the humanitarian organization identified is the economic pattern, where minors are spoils of war because they are kidnapped from war zones by the same people who murdered their parents.

“Some go to the Red Cross, others are taken to homes, where these trafficking networks appear that are responsible for managing all adoptions in an express way; in the years 1982 and 1983, there is a great ease in the mayor’s offices generating documents,” reports the researcher.

Three reunions in 2023

Despite all the obstacles, Pro Búsqueda, which completed 29 years of work, managed to reunite three cases of children who disappeared during the armed conflict in El Salvador.

Sophia was adopted when she was approximately five months old by a family in London, England, and was reunited with her family on March 21.

Pedro, who was a native of the department of Chalatenango, was approximately five years old when he was separated from his mother, who died without finding his whereabouts.

His brother, however, persisted in the case until July 4, when he managed to reunite virtually.

The last story is that of Flor, who was separated from her family and offered up for adoption with forged documents. She resides in the U.S. and was able to meet her siblings on July 24, via a virtual call.

The Peace Accords, which ended the civil war between the government and the former guerrillas of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), did not include the issue of the forced disappearance of children.

Three decades later, Pro Búsqueda activists tell Expediente Público that they will remain faithful to one of the thoughts of Jon Cortina, their founder: “as long as impunity is still there, part of our job is to end it.”