* Operations against Nicaraguan opponents and civil society organizations include not only the confiscation of assets, but also accounts, savings, and deposits involving private banks.

**Expediente Público asked the banks to clarify how many accounts they closed by order of the regime and under what pretexts, but they did not issue a response.

***In recent months, the accounts of Nicaraguan opponents and organizations of refugees and political persecuted people in Costa Rica have also been closed.

Expediente Público

The freezing and closure of accounts, the cancellation of credit cards, certificates of deposits, insurance policies and other banking services were all part of the repressive instruments of the Ortega-Murillo regime against its opponents, according to victims and organizations consulted by Expediente Público.

In some cases, banks have the “courtesy” of communicating to their customers the decision to cancel their services; the main argument they give is the application of the current legal framework for the prevention of money, goods or asset laundering.

But most of those affected are not even told what motivated the bank’s decision to freeze or suspend services, let alone what happened to the money or assets in their accounts.

Nicaraguans who have faced political accusations, interviewed by Expediente Público, take it for granted that these actions are part of the proceedings against them, others attribute it to their relationship with a non-governmental organization (NGO), and still others simply do not understand why the bank they trusted made that decision.

Subscribe to the Expediente Público newsletter and receive more information

In the midst of the terror that comes with reporting these abuses, new stories emerge every day on this issue. Among the victims, almost four thousand Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) stand out, which since December 2018 the regime began to close by stripping them of their legal status.

The use of the financial system against opposition and dissent in Nicaragua has become so recurrent that the United Nations (UN) Group of Human Rights Experts on Nicaragua (GHREN) included it in the second report on the situation in Nicaragua, presented in early March.

According to GHREN, the regime’s persecution of real and perceived opponents “has become more subtle,” which now deprives victims of other rights, including their livelihoods, whether work and income, bank accounts, and other assets.

In context: Daniel Ortega empowers the military to supervise Nicaragua’s banks

Since 2019, they began to freeze bank accounts and certificates of deposit, and canceled credit cards, insurance policies, and other services to individuals or legal entities that the regime considers oppositional.

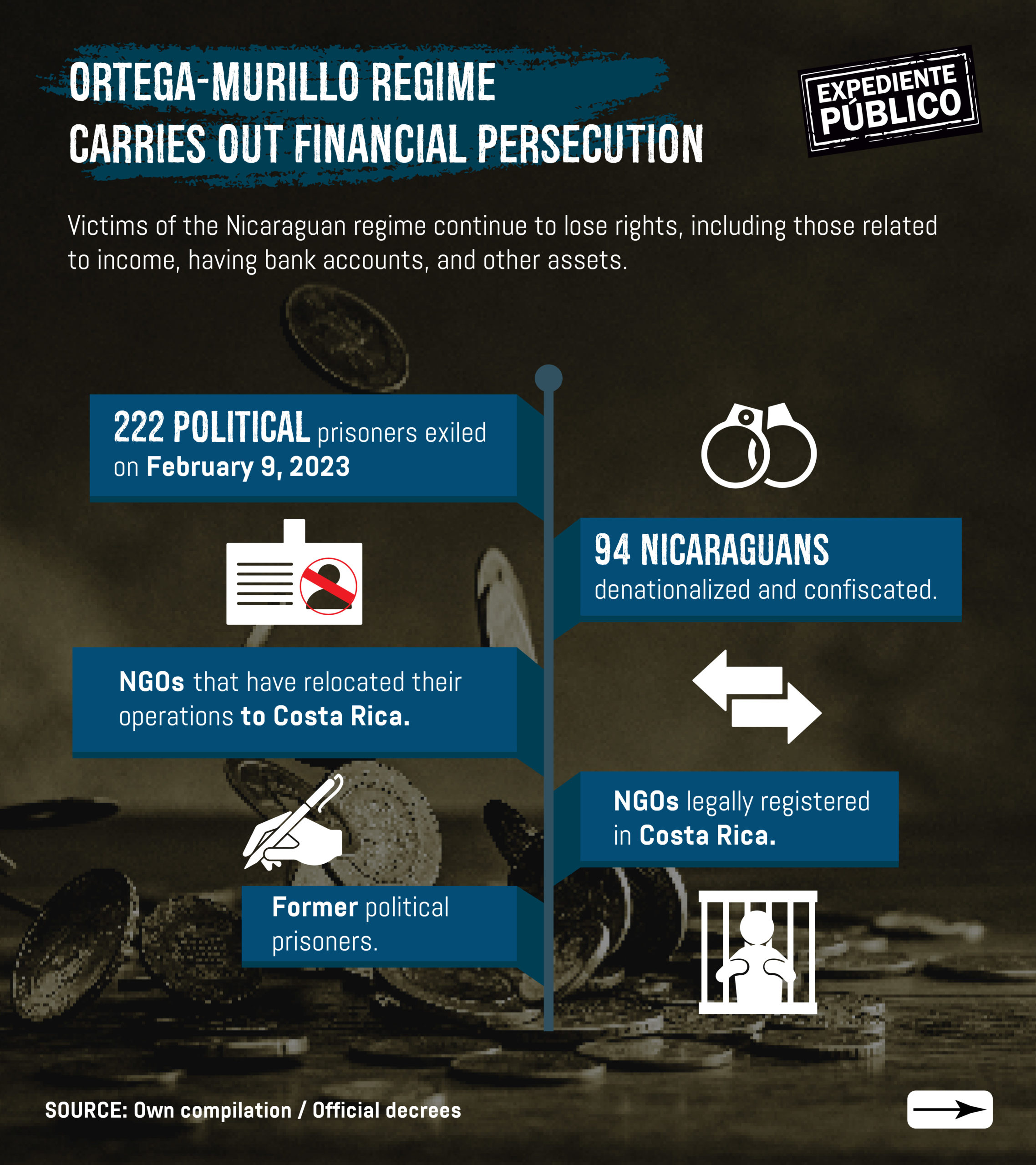

Among those affected are also 222 former political prisoners who on February 9, 2023, Daniel Ortega banished to the United States on the so-called Freedom Flight, and then stripped them of their nationality and confiscated their assets.

Then came the 94 Nicaraguans who, days after that flight, were denationalized and had their assets confiscated.

Repression crosses borders

The first cases of account closures occurred in 2019 and five years later, instead of ending, they continue, but now also in Costa Rica, where thousands of politically persecuted people have taken refuge.

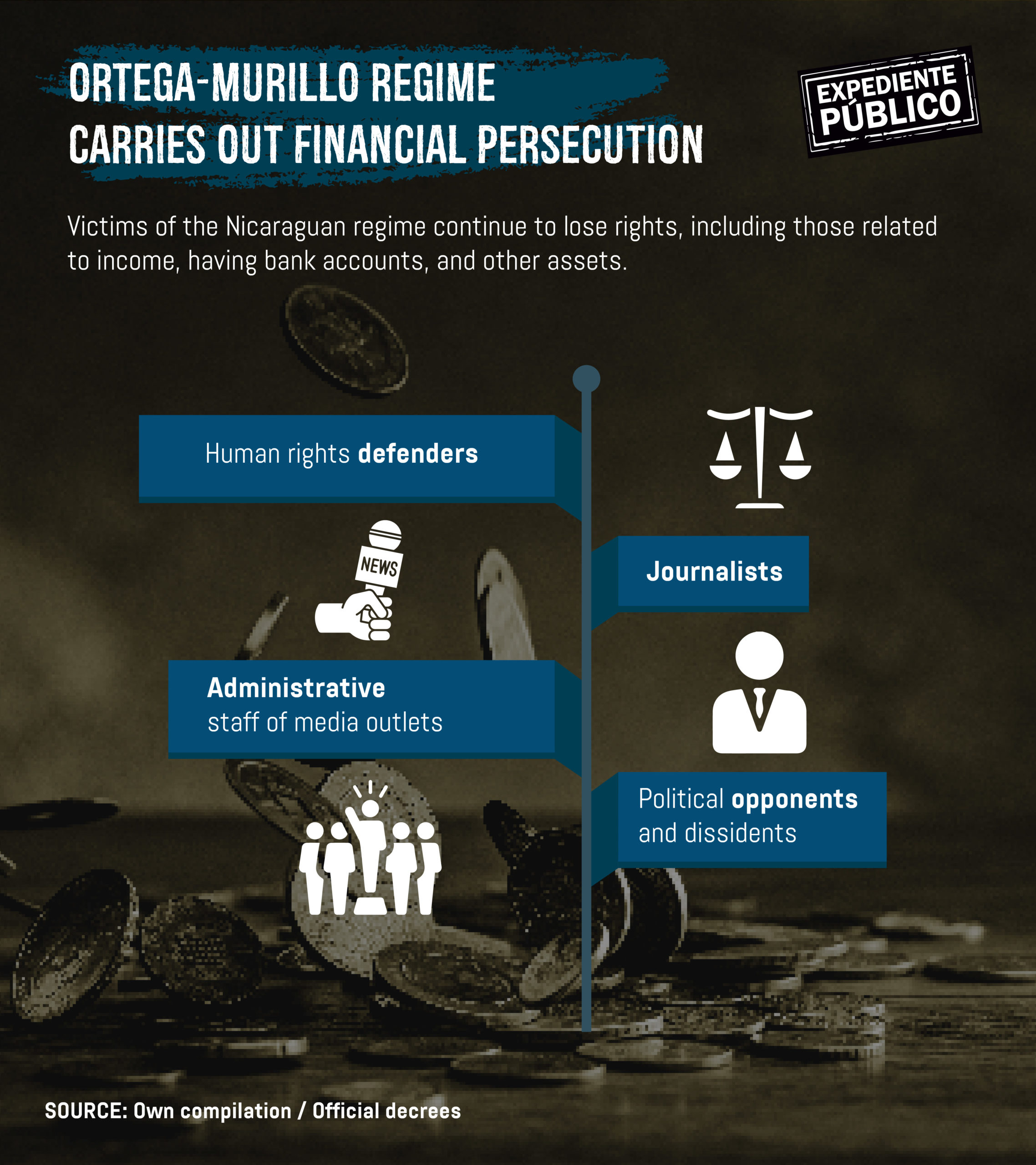

Over time, some NGOs that moved their operations to Costa Rica and others that were born in that country as a result of the crisis, other former political prisoners, human rights defenders, journalists, administrative staff of the media, and opponents in general have been added to the blacklist of the banks.

The measure is now being replicated in that country and there are fears that it will also reach the United States, since these two countries are home to some of the leaders of political, social, business, and student organizations, former political prisoners, NGO directors, journalists, human rights defenders, and other groups that constitute the main focus of Ortega’s attack.

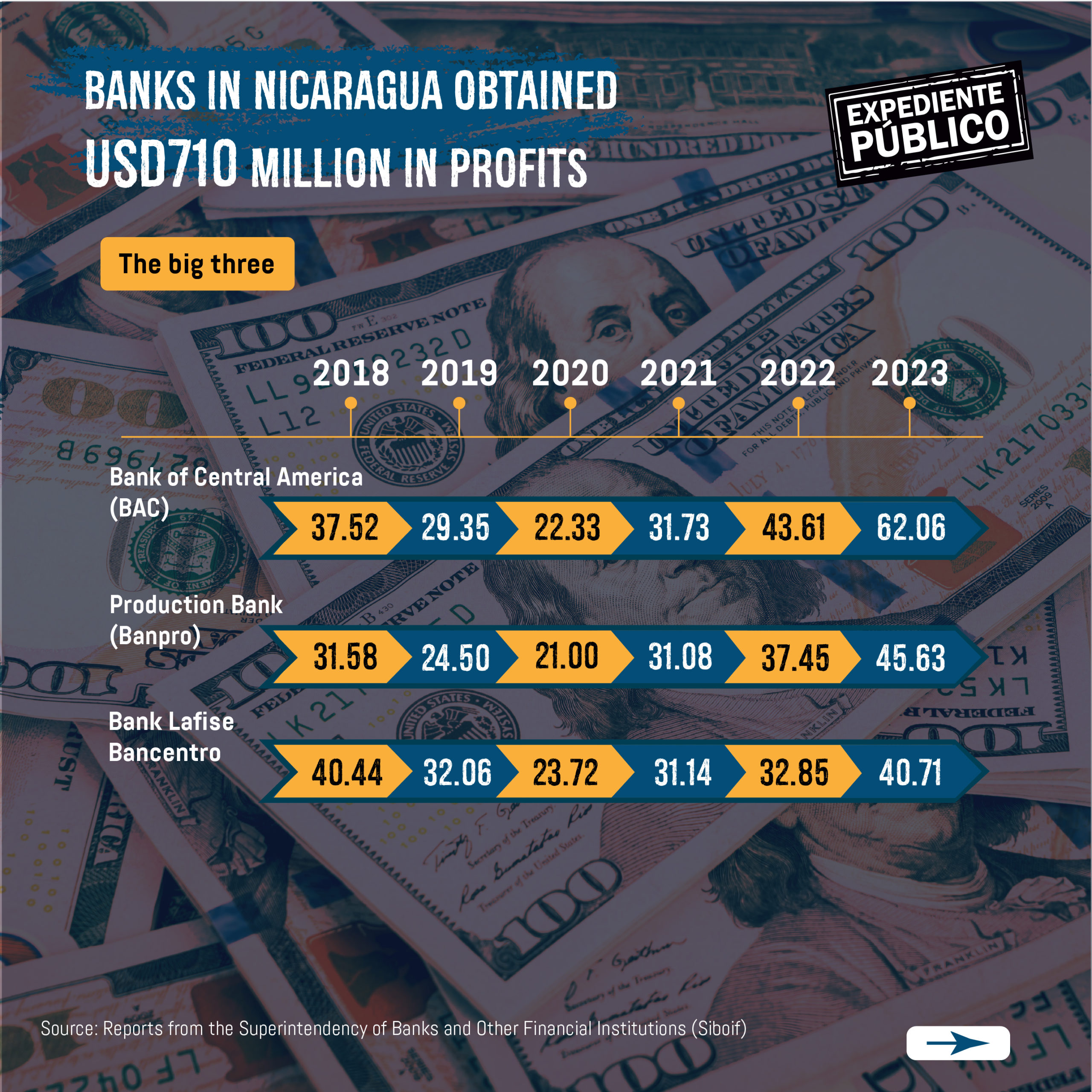

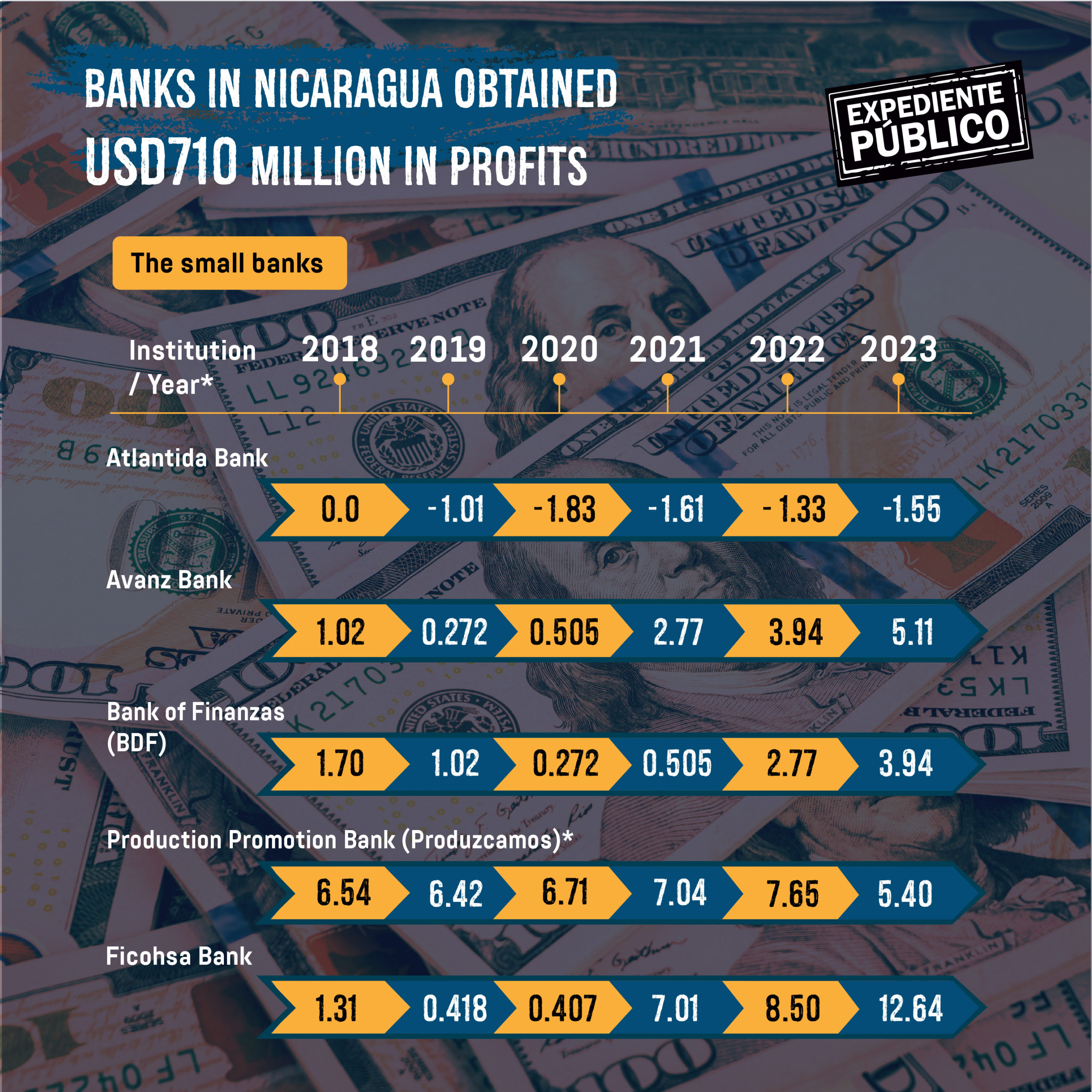

Four main entities have been singled out: the Bank of Central America (BAC Nicaragua), Banco Lafise Bancentro, Banco de la Producción (Banpro) and Banco de Finanzas (BDF).

On the other hand, there are cases of financial institutions that closed accounts, but still rigorously collect their personal loans through various mechanisms. And as in any other case, not honoring them in the established times and ways damages the credit history of the affected person, even in Costa Rica.

What happened to the money donated to NGOs?

One of the first victims of the new repressive method was the now-defunct Fundación del Río, an environmental organization led by activist Amaru Ruiz, who was also denationalized in 2023.

In December 2018, in the midst of the socio-political crisis, the deputies of the National Assembly cancelled his legal status and confiscated his assets; and between January and February 2019, Banpro froze $25,000 donated by international cooperation to finance projects of la Fundación del Rio, an organization that since 1990 had been developing in defense of the natural ecosystems of southeastern Nicaragua.

To date, Banpro has not notified Ruiz if the money is still frozen or if Daniel Ortega’s regime ordered it to be transferred to the state.

Since then, the list of those affected by this repressive measure continues to grow and in cases where banks notify the affected party, they do so under the argument that they are complying with the provisions of Resolution CD-SIBOIF-524-1-MAR5-2008, which is the Standard for the Management of the Prevention of the Risk of Money, Property or Assets Laundering and Financing of Terrorism.

Banks also apply Law 977 Against Money Laundering, Financing of Terrorism and Financing of Proliferation Weapons of Mass Destruction.

In addition: Anti-Money Laundering Laws: The Political Weapon of Daniel Ortega’s Regime

The environmentalist and former director of the extinct Fundación del Río, Amaru Ruiz, warns that, if they now sustain these closures with the supposed compliance with Law 977, in the case of the Fundación del Río, they could not do so, since that law was approved in May 2021, almost two years after their money was frozen.

But it wasn’t just closed NGOs that had their money frozen, but also individuals.

In June 2021, that is, almost two years before he was included in the list of the 94 Nicaraguans whose nationality was revoked and their assets confiscated, a political analyst wanted to make a withdrawal from his personal account he had at Banpro, but he could not withdraw his money; the institution’s cashier told him that his account was frozen.

Knowing that his accounts were frozen alerted him and prompted him to leave the country, so he could not return to the bank to demand an explanation, since before February 2023, when he was included in the list of the 94 denationalized, he was never involved in any court case that justified the measure.

“We were robbed”

These examples are representative of the actions of the banks, described by different affected parties interviewed by Expediente Público as a robbery or abuse, perpetrated against them by the financial institutions in which they trusted the safekeeping of their money.

This practice continues to be applied in the same way to legal entities that, like Fundación del Río, were stripped of their legal status, but also to individuals who were involved in legal processes.

However, Expediente Público found cases of people who have not been linked to any accusation, but who, by “someone’s” decision, were also robbed of the right to have bank accounts, certificates of deposits, insurance policies and to use credit cards.

In addition, the repressive practice involves people in refugee status or asylum seekers in Costa Rica, where for several months, without convincing justification, the BAC and Lafise have closed accounts.

There are also exile organizations affected in that country that maintained a financial relationship and others have been denied service, according to complaints to Expediente Público.

Due to the diversity and current location of those affected, it is not possible to have precise data on the number of accounts, certificates of deposits, insurance policies and credit cards that the banks have “frozen” or canceled of the people and organizations considered by the Ortega Murillo regime as opponents.

Banks do not respond

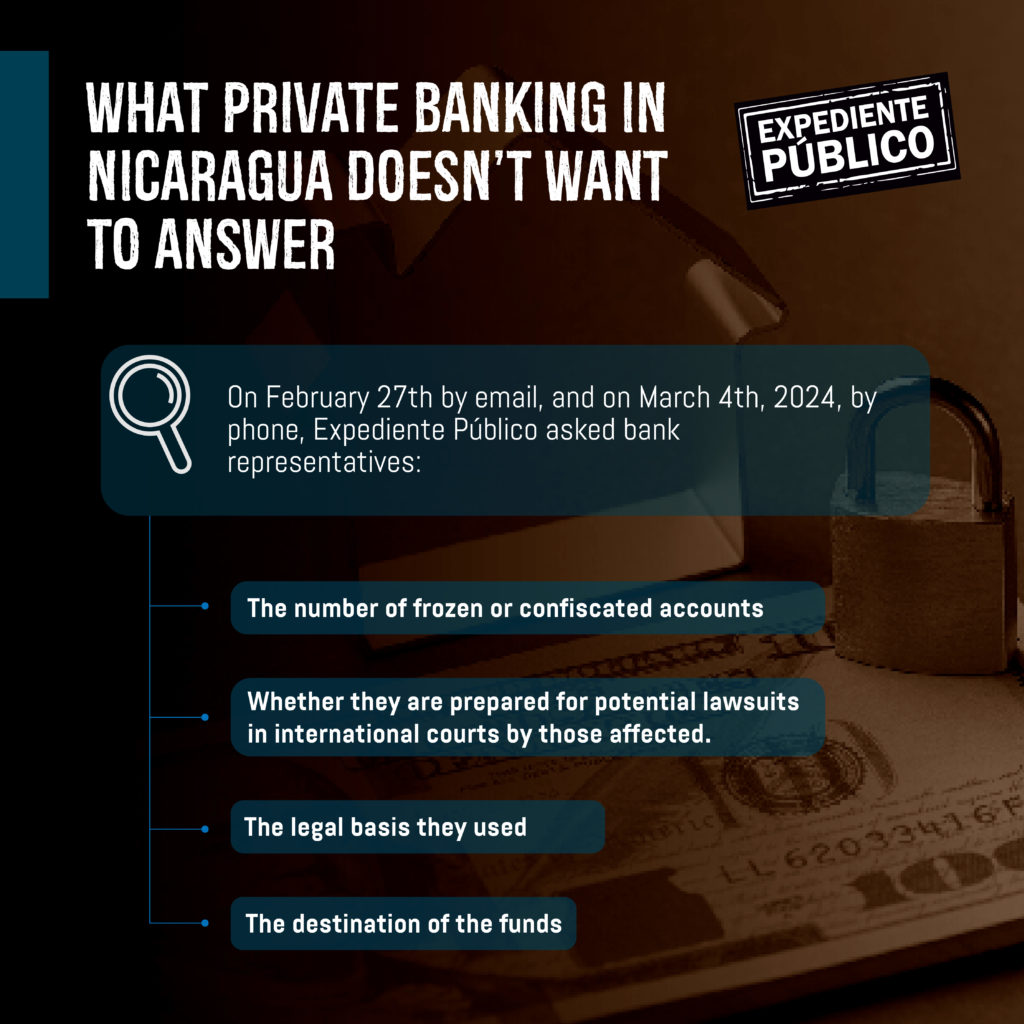

On February 27, Expediente Público sent e-mails to BAC Nicaragua, Banpro, BDF and Lafise Bancentro and to the BAC subsidiaries, Banpro and Lafise in Costa Rica, requesting interviews with their officials or at least an explanation about these measures against exiles and exiles.

On March 4, the public relations managers of the banks were contacted by telephone to insist on the request, and in the case of the BAC, also the public relations agency that works with them, but in none of the cases was a response obtained.

At the time of this publication, no bank had responded to our queries.

Each of the banks was asked about the number of cases of this type they processed, the legal basis they used and, in the case of frozen accounts and certificates of deposits, the destination of the resources that were in them at the time of applying the measure.

They were also asked if they are prepared for possible lawsuits in international courts by affected customers.

Also Read: Nicaraguan Regime Will Access Bank Information Without Users Knowing

Gonzalo Vila, a specialist in money laundering and a senior official of the financial system in Latin America, told Expediente Público that banks have in their defense to be complying with guidelines from the entities in charge of the prevention of money laundering.

In addition, remember that in all countries banks are regulated and receive guidance from these bodies and must comply, because if they do not do so, they are exposed to fines and other sanctions that can lead them to bankruptcy.

In 2021, the National Assembly approved the Reform to the General Law on Banks, Non-Banking Financial Institutions and Financial Groups, as well as the Capital Market Law and the Law on the Superintendence of Banks and Other Financial Institutions.

In 2022, the regime also approved 15 regulations and three reforms to the financial system, which include fines, under the argument of strengthening banks and complying with the recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force of Latin America (GAFILAT).

In the presentation of the report to the 2022 parliament of the Superintendent of Banks, Luis Montenegro, reported that they carried out 308 inspections and charged for 13 sanctions, in the amount of 99,600 córdobas, less than 2,700 dollars.

The president of the Parliamentary Economic Commission, Wálmaro Gutiérrez, celebrated Montenegro’s presentation in 2022, because “without a doubt, we have one of the most solid and stable systems in Central America that gives confidence to users and gives a powerful signal to investors, especially foreign investors.”

However, Vila admits that the problem is that in the face of the weakening of institutions and the rule of law in Nicaragua, there will always be the question of what is the real reason why organizations and individuals are included in these lists.

In fact, the same banks were victims of the regime when, on February 3, 2023, it cancelled the legal status of the Association of Private Banks of Nicaragua (Asobanp), which since 1993 had brought together the country’s private banks.

Asobanp was the bankers’ interlocutor with all the governments that passed, including Ortega-Murillo himself, in the negotiations related to the approval of laws and regulations related to the regulation and operation of the financial system.

During its almost thirty years of life, Asobanp was a member of the Superior Council of Private Enterprise (Cosep), which in March 2023 also lost its legal status along with 18 other business chambers.

As a member of Cosep, Asobanp was part of the dialogue-consensus model that, for more than a decade, governed the relationship between big business and the government and that Daniel Ortega presented as one of his great achievements.

However, as a result of the rupture of the model, when in 2018, after the imposition of a failed social security reform, a socio-political crisis was unleashed that, according to the GHREN, to date continues to add victims – the representatives of big capital did not escape it.

Cosep President Michael Healy, Vice President Álvaro Vargas, former President José Adán Aguerri, and Banpro CEO Luis Rivas were among the businessmen accused and convicted of alleged conspiracy to undermine national integrity, illegal carrying of firearms and manufacturing weapons, trafficking and use of restricted weapons.

They are among the 222 political prisoners exiled on the so-called Freedom Flight on February 9, 2023 and subsequently stripped of their nationality and having their assets confiscated. Healy died earlier this year.

The private sector think tank, the Nicaraguan Foundation for Economic and Social Development (Funides, Fundación Nicaragüense para el Desarollo Económico y Social), was also cancelled in 2021, its executive director, Juan Sebastián Chamorro, was also imprisoned and banished, its directors were investigated and their accounts frozen.

Among the directors of Funides were Juan Carlos Sansón Caldera, general manager of BAC Nicaragua and Edwin Mendieta Chamorro, secretary of the Avanz bank of the Pellas Group.

For Gonzalo Vila, director of Latin America at Association of Certified Financial Crime Specialists (ACFCS), a company that certifies money laundering specialists, the Nicaraguan legal framework has many loopholes that allow both banks and the agencies in charge to act with discretion.

These measures within the financial system coincide with the use of the entire state apparatus to persecute real or perceived opponents of the regime.

Of interest: Regime accuses the Catholic Church of money laundering and orders the closure of its bank accounts

SIBOIF in the crosshairs of international sanctions

The report presented by the United Nations (UN) Group of Human Rights Experts on Nicaragua (GHREN) at the beginning of March recommends to the international community that, when assessing Nicaragua’s compliance with anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism rules, they take into account the Recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), applying the principle of do no harm.

In addition, on November 15, 2021, the U.S. Department of the Treasury included the Superintendent of Banks and Other Financial Institutions (Siboif), Luis Ángel Montenegro, on the list of appointees.

According to the statement issued by the Treasury Department, in his role as superintendent, Montenegro authorized the banks to hand over financial information on three senior officials and businessmen who were under investigation under Law 1055.

In addition, in April 2020, it issued regulations derived from the reform of Law 842, Consumer Protection Law, which prohibits banks in Nicaragua, without a reason recognized by Nicaraguan law, from denying financial services to customers, including persons designated by the U.S. Department of the Treasury.