*In an interview with Expediente Público, the new director of the Honduran police force, Commissioner Gustavo Sánchez argues that “purging police forces was part of a strategy to tie the institution’s hands.” He defends the reinstatement of more than 2,000 officers, attributing the decision to the institution’s being shorthanded.

**Analysts consider the reinstatement of these officers to be of national security concern for Honduras.

Expediente Público

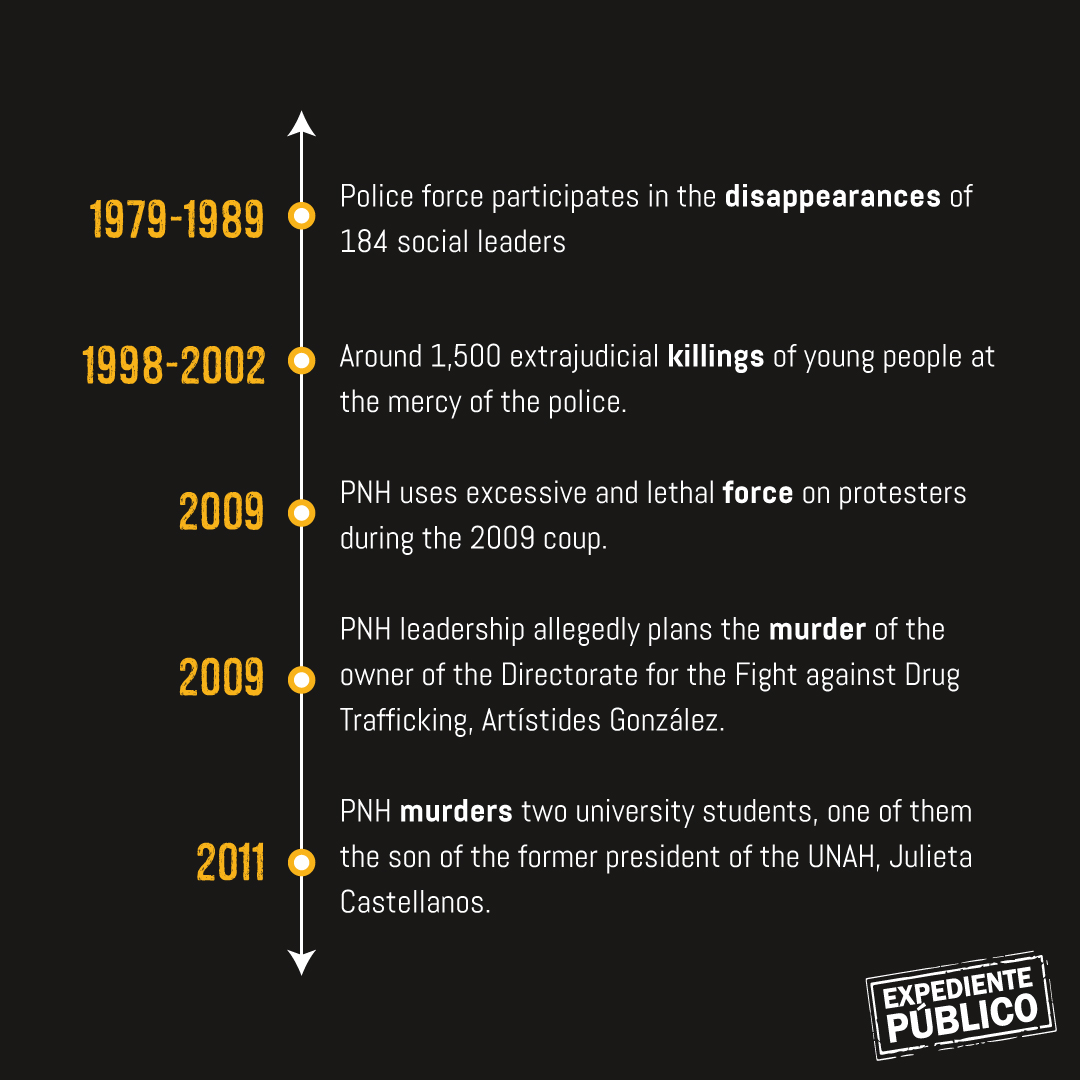

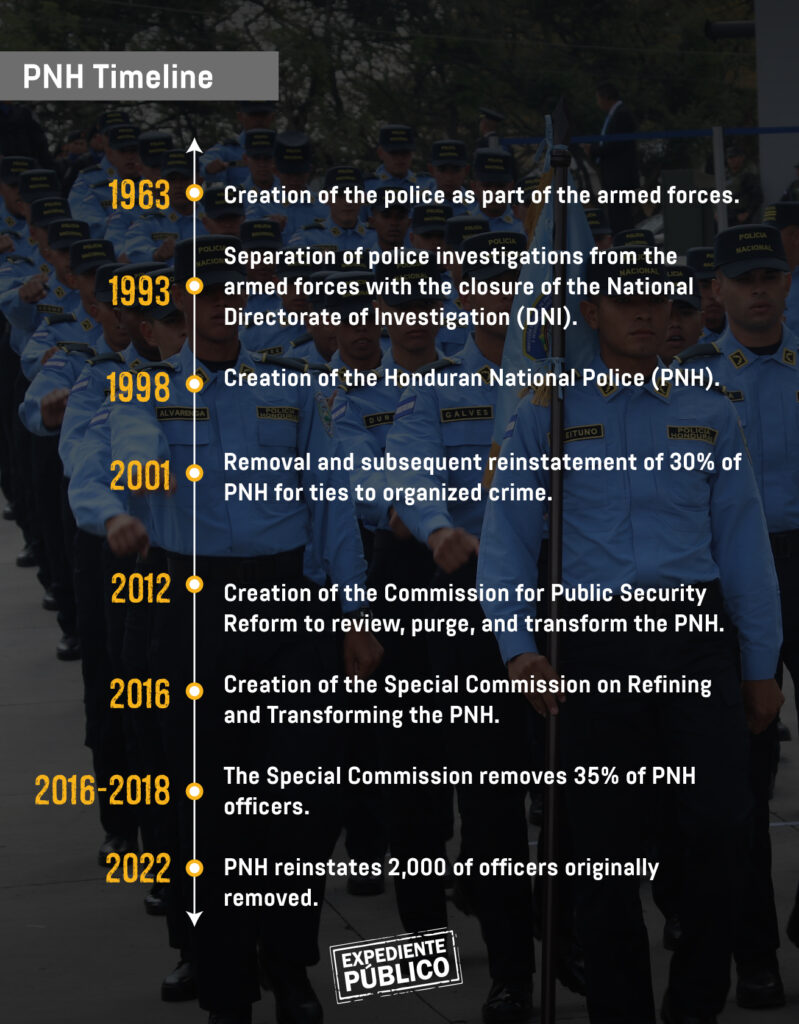

In 2016, the Honduran government began one of the continent’s most ambitious policies to date to purge the national police. This policy affected 35% of the Honduran National Police (PNH), which totaled to 4,678 officers. Six years later, the institution is questioning that process by welcoming police reinstatement.

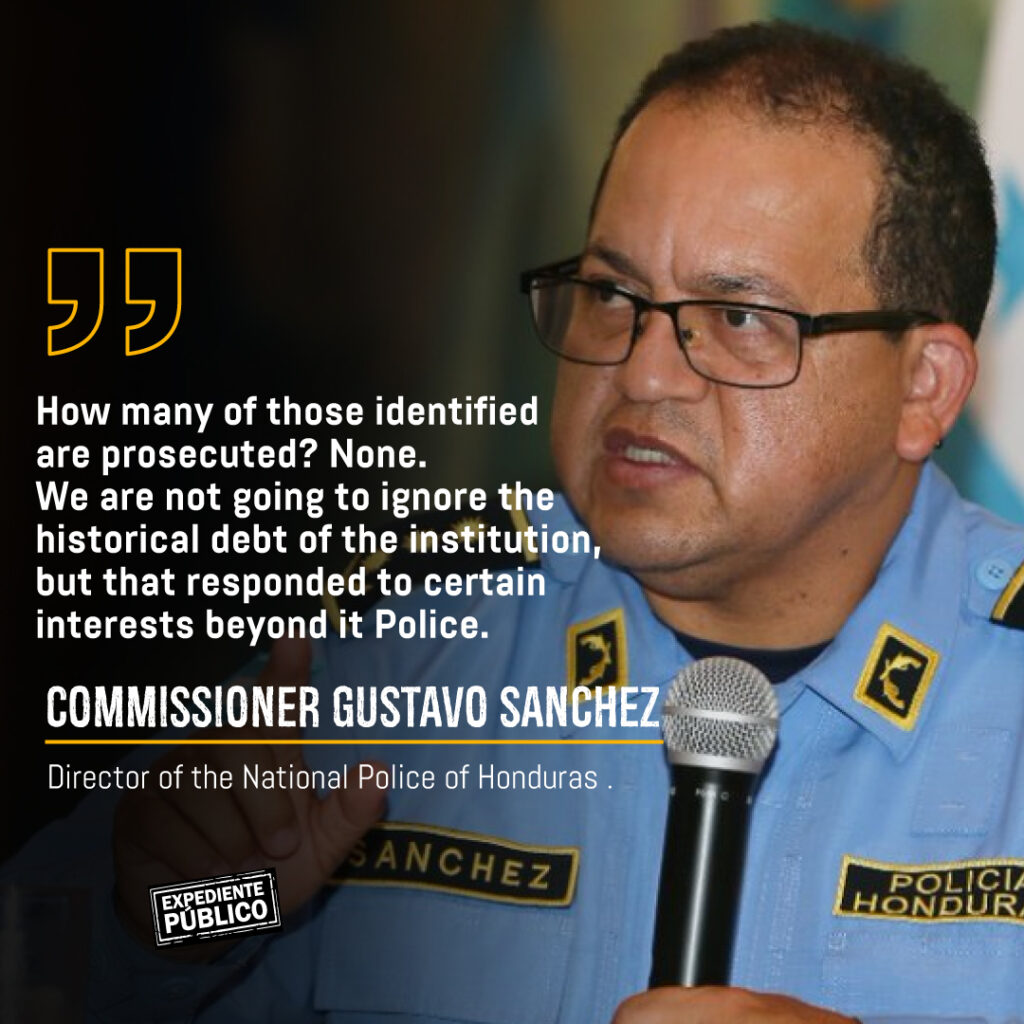

Director of the PNH, Commissioner Gustavo Sánchez is responsible for 19,000 police officers. In an interview with Expediente Público, Commissioner Sánchez argues for the reinstatement of police officers due to worsening crime rates in the Central American country. For this reason, the institution has begun to reinstate 2,000 officers that have asked to return to the police force.

In Honduras, the homicide rate for 2021 was 40 per 100,000 inhabitants, according to the National Observatory on Violence of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras. Statistics like these make the decision to reinstate police officers seem justified. The minimum average of police officers suggested by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) is 300 per 100,000 inhabitants. In Honduras, the rate is 187 per 100,000 inhabitants. Even in areas such as La Mosquita, which is in the eastern part of the country and the primary entry point for drugs trafficked into Honduras, police presence is minimal at best.

Reinstating 42% of police officers previously let go by the State does not seem to come down to a human resources decision. Sánchez states that the most recent layoffs were part of Juan Orlando Hernández government´s (2014-2022) strategy to control the PNH and provide a justification for the militarization of security forces.

“Layoffs that resulted in purging 35% of the police force were part of a strategy to tie the hands of the institution. Today, however, the PNH has the legal means to deal with the issue internally. There has always been an interest in maintaining the PNH in a distant, anxious state to allow other institutions to take on functions that the Constitution does not allocate to the police.”

Read: Entrevista con el nuevo director de la Policía Nacional de Honduras

Expediente Público consulted other sources that considered the reinstatement of police officers to be of national security concern and a step backwards in national advances to clean up the institution between 2016 and 2018, a process that Honduran citizens and the US government supported.

“The decision is surprising because it translates into an outright denial of the facts, disrespect for victims of police forces participating in collusion and organized crime, and a disconnect from recent history,” stated Julieta Castellanos, former president of the Universidad Autónoma de Honduras (UNAH), in a letter, which she wrote on April 28, 2022, to President Xiomara Castro and her husband, Manuel Zelaya, former president and presidential advisor to Castro. Important to note is the academic’s relationship with the police. In 2011, a group of agents murdered her son, Rafael Vargas Castellanos and his friend, Carlos Pineda.

The last institutional cleanup

Since its inception in 1998, the PNH has faced several efforts to clean up the institution. Most of the initiatives have failed due to lack of government commitment because of conflicts at work, personal interests behind firings, or opposition from the police. However, the 2016 institutional cleanup of the PNH is the most successful of all efforts.

“Compared with other years, the most recent cleanup of the institution achieved some noteworthy goals, such as removing important people, in using a top-down approach. Despite all the criticism, the process was more legitimate than others in the past,” Eric Olson, director of policy and strategic initiatives at the Seattle International Foundation (SIF), fellow at the Wilson Center, and expert in security and political issues in the Western Hemisphere, commented to Expediente Público.

Read: Pobreza y corrupción policial alimentan las extorsiones en Honduras

As was the case of previous processes, the 2016 removal of police officers gave rise to a scandal. The New York Times revealed that 25 police officers, including leadership, were involved in the murders of former members of the Directorate for the Fight against Drug Trafficking, Arístides González and Alfredo Landaverde.

The report showed that three former directors of the PNH planned the crimes under orders of the powerful drug trafficker, Wilter Blanco, who currently serves time in the US. Two former police chiefs, the current minister of security, Ramón Sabillón and Juan Carlos “El Tigre” Bonilla, currently being extradited by the US, supposedly shelved the cases.

The same occurred in 2011 with the murder of two young men, among them the son of former UNAH President Castellanos, at the hands of the PNH. The New York Times exposed the institution and verified that the Commission for Public Security Reform (CRSP) had not made any significant changes or reforms, despite spending 41 thousand Honduran lempiras or 1.6 million dollars in 2012 on reform programs.

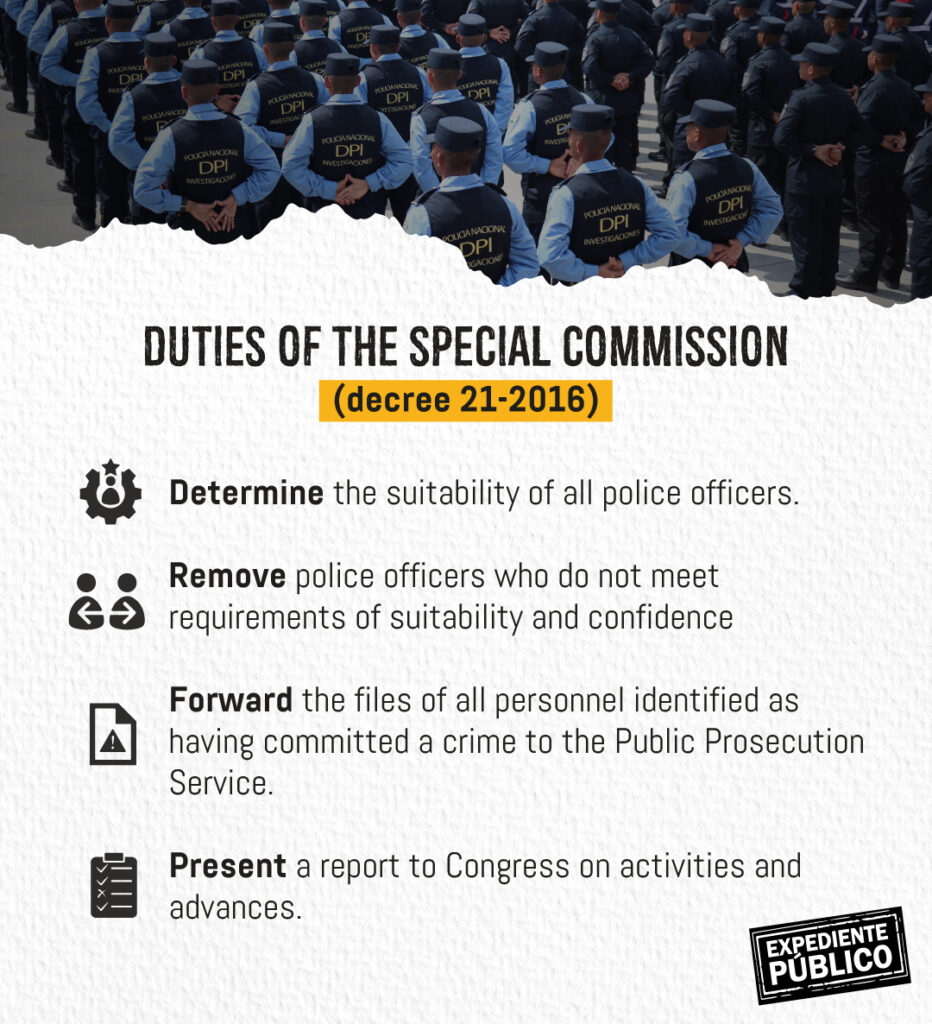

Due to domestic pressure, on April 12, 2016, former President Juan Orlando Hernández created a commission composed of former Minister of Security Julián Pacheco, attorney Omar River, former President of the Supreme Court Vilma Morales, and evangelical pastor, Alberto Solórzano to purge police ranks.

At onset of the increased domestic skepticism, the Special Commission on Refining and Transforming the PNH removed 43% of high-ranking police officials in a little under a few months, through restructuring the institution by suspending officers or provoking voluntary leave.

One of the first police officers suspended by the commission was the current Minister of Security Ramón Sabillón, who alleged that the whole process was a setup and that the Hernández administration wanted revenge after, in 2014, Sabillón captured members of the Cártel de los Valle, alleged associates of the former president.

Read: Los hermanos Hernández en Honduras, crónica de drogas, poder y dinero

“Counterfeit goods and leaked documents were the result of a desire to purge members of the PNH who did not support the Hernández presidency,” said Sabillón before seeking asylum in the United States for five years. The current director of the institution, Gustavo Sánchez believes that incriminating the PNH was a strategy used by the government to control the police.

“How many police officers identified by the commission were brought to justice? None. Without failing to consider historic institutional shortcomings, we can recognize that there were other interests at play that went beyond problems with the PNH,” Sanchéz said.

Sánchez refers to PNH leadership, including former police chiefs, Salomón Escoto Salinas, José Luis Muñoz Licona, and Ricardo Ramírez. The first two were accused of being part of the “death squad” of Battalion 3-16 of the armed forces during the 1980s. Ramiréz was accused of money laundering.