*Matt Schrader, advisor on Chinese affairs at the International Republican Institute, asserts that China “is happy” dealing with dictators and helping them remain in power.

**Chinese companies break the rules on transparency in the countries where they do business and thereby worsen existing problems, through bribes and other forms of corruption.

***Systems that targeted dissidents and opponents of Nicolás Maduro and Rafael Correa.

Expediente Público

The presence of the People’s Republic of China in Latin America is extremely dangerous for transparency and democratic institutional structure in the countries of the region due to China’s affinity with dictators and its willingness to make corrupt deals with politicians in Latin America, said Matt Schrader, International Republican Institute (IRI) advisor on Chinese affairs, in an interview with Expediente Público.

Schrader was one of the topical experts at a forum on Chinese influence and interests in the world, coordinated by the International Republican Institute’s Center for Global Impact and held in Washington DC.

“I think the reason you need to worry about it is that China is completely fine with working with dictators who want to buy technology to monitor dissidents. They are quite happy to make corrupt deals with politicians who want the money so they can carry out their own projects,” said Schrader, whose specialty is explaining how China is affecting the political system of other countries, and advising on containing it.

According to Schrader, China is showing up all over the world and “not everyone understands what is happening or why.” But he warned that the Chinese presence implies threats to institutions, transparency, national security and security in Latin America.

He noted that many citizens are concerned that China is a danger to important institutions, such as democracy, the free press, and government accountability.

“When large Chinese companies and agencies go abroad, they are happy to work with people in other countries who don’t care about democracy either, and they are happy to help them stay in power,” warned the IRI adviser.

He acknowledged that “not all dealings with China or all trade with China are corrupt” and “there are many good ways to do business with China that benefit both sides, but it’s just a fact that China follows a different set of rules.”

“If you care about transparency, accountability, and the rule of law in your country, then the people who are in charge of China are not really your allies, because that’s not important to them,” Schrader warned.

Under rules of corruption

Schrader told Expediente Público that the People’s Republic of China’s corrupt practices can be seen in almost every deal where they have been involved in Latin America.

He pointed out that when a Chinese company or millionaire moves into another nation, they are not obligated to play by the same rules as companies from the United States, or European Union government agencies.

“They know they’re not going to get in trouble in Beijing if they bribe a local official, or if they break local rules in some way; environmental rules or transparency rules or public procurement rules,” he added.

According to Schrader, people are frustrated by corruption and cronyism, as well as the ways politicians are getting rich without benefiting the people. “When a Chinese state-owned company comes along, they have no problem playing by those rules, making existing problems even worse.”

In his opinion, it has “often been seen” that when Chinese involvement in a country grows, many of the problems that people are already frustrated with become worse.

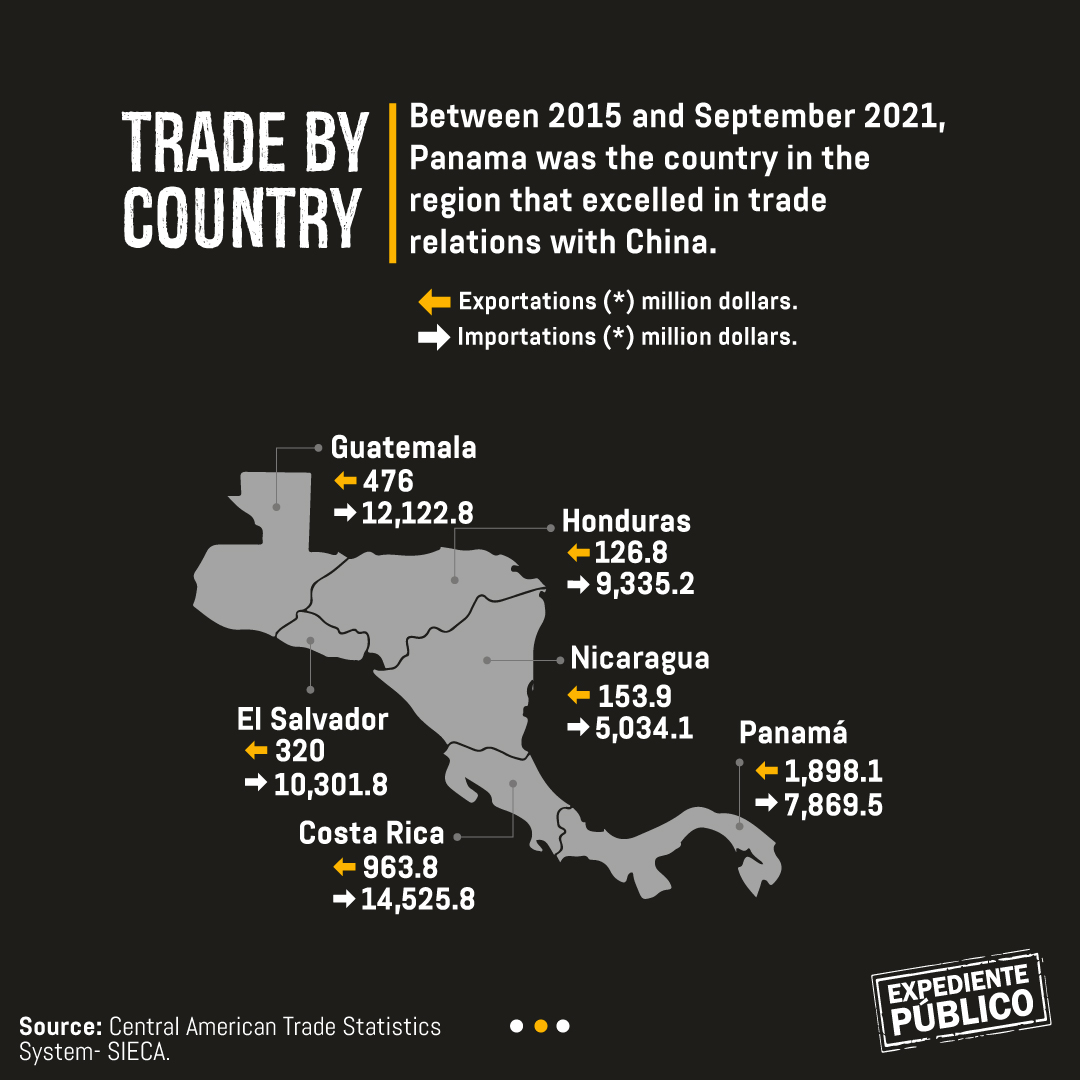

In many Central American countries, Chinese investment has exacerbated conditions of social, political, and environmental vulnerability. Support for human rights, workers rights, and accountability practices are not a priority in China’s relations with its partners.

National security

Schrader said that the debate over whether China is a threat to the national security of the United States is one of the most complicated issues for that country.

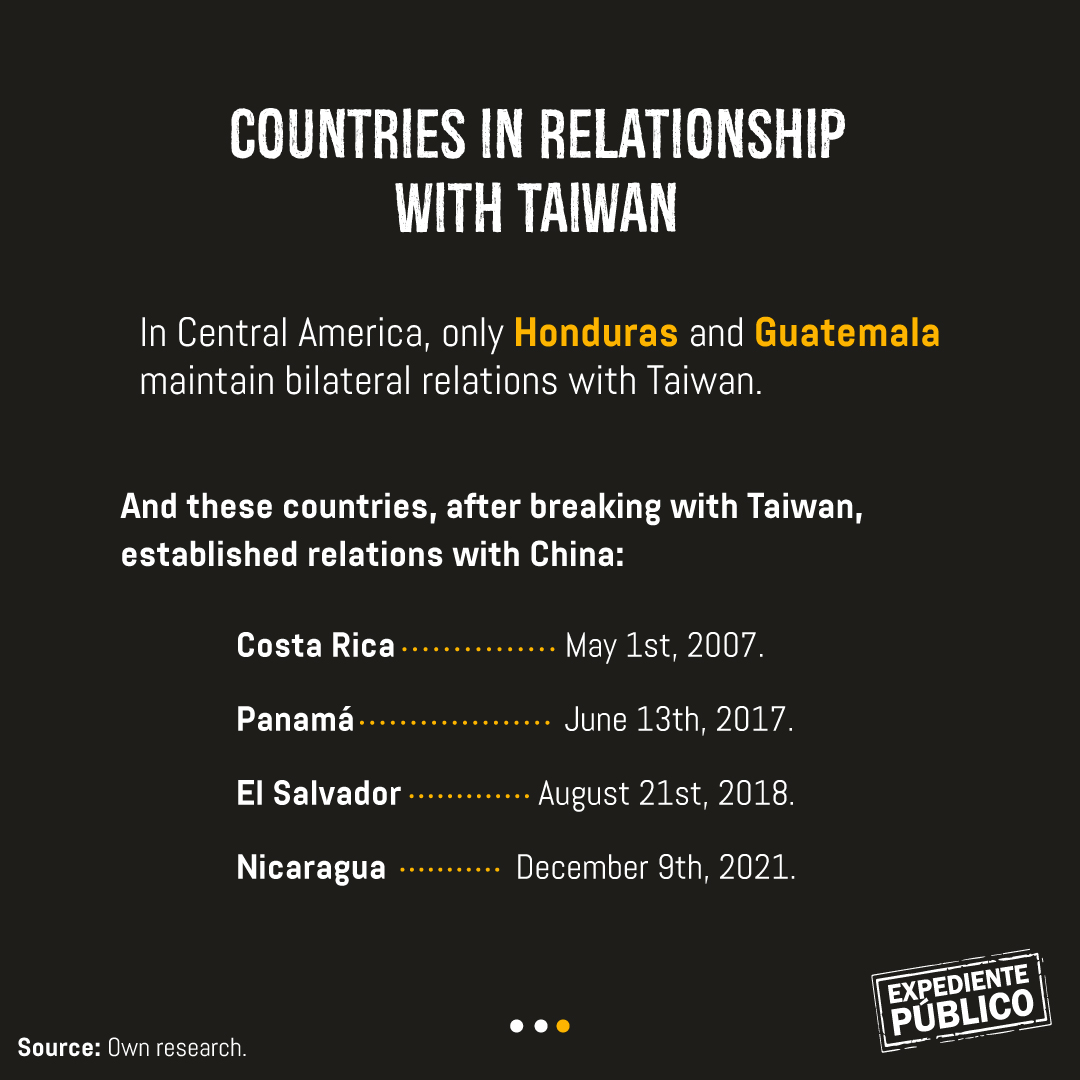

“There are people who see it as a national security issue, who look at the military, or at military technology, or think about Taiwan,” he said.

Nevertheless, he considers that China’s influence on democracy is more worrying than the impact it might have on national security.

According to Schrader, people who are concerned about national security are focused on the possibility that China could, for example, install satellite listening stations in Western Hemisphere countries.

“This has already happened in Argentina. There are rumors that they want to do it in Central American countries; basically China wants to cooperate with countries in the Western Hemisphere on a military basis because it could give China an advantage in a potential war with the United States over some place like Taiwan,” he explained.

According to Schrader, this is why there have been cases of Chinese businessmen making unprecedented offers to buy islands in some Central American countries, “and it is not very clear what the point is, except, as you know, potential satellite listening stations, so if you’re concerned about national security, that’s probably what you’re worried about.”

Schrader mentioned the case of Perico Island, on the Salvadoran side of the Gulf of Fonseca. Chinese businessman Bo Yang, with ties to the Chinese government, acquired the small island in 2019, provoking concern in El Salvador and the United States.

China and political espionage

Schrader cited two specific cases in Latin America where the People’s Republic of China collaborated with authoritarian regimes to spy on their citizens, especially their opponents.

“In Venezuela, a Chinese technology company helped implement a national identification system that was actually used to help target dissidents, denying them social benefits,” Schrader explained.

This is a reference to a contract with the Chinese company ZTE, which developed the system known as the “Carnet de la Patria,” criticized as a mechanism of “citizen control.”

China provided the technology and technical assistance to help process vast amounts of data and monitor people the government considered “enemies.” The equipment included television camera systems, devices for taking fingerprints, facial recognition, and word algorithm systems for the internet and for conversations.

Schrader also mentioned the case of another Chinese company that helped set up a national surveillance network in Ecuador “which was used by the police to help them go after dissidents.”

The Chinese system was installed in Ecuador in 2011, during the administration of Rafael Correa, who also acquired a huge debt with the Asian country.

China and institutionality

Schrader said that a large amount of research conducted in Latin America, Southeast Asia, Africa and the Pacific Islands warns that national institutions see themselves as having a commitment to China, which affects their natural development.

“If your country has good media institutions; a strong press; a strong judiciary; if you have strong transparency, disclosure and accountability laws; then you are much less likely to see these worrying effects,” Schrader explained.

He pointed out that it is not about saying that they should not do business with China, but he warns that “it has to be with a process that ensures that China, which does not value democracy, does not weaken the other country’s democracy.”

As an illustration, Schrader pointed to the significant differences between China’s relationship with Chile (a country with strong democratic institutions) and its relationship with Venezuela.

The role of the United States

For Schrader, the United States “is not as powerful as people think we are.”

From his experience, he noted that where there is an American presence, people want to know what the United States can do for them. “And we can do a lot,” but the actual ability to influence events on the ground is much more limited than what people usually think, he said.

He recalled how authoritarian governments around the world accuse the United States of being the one “behind everything” they do not like. “I wish we were that influential, but we’re not. We don’t have that power.”

He emphasized that the United States can help, “but our ability to help may not be as much as you would hope for.” He expressed his hope that his country will do more to offer technical assistance to the countries that are negotiating Silk Road agreements with China.

“And I think that people in Latin America should also be saying to other major democratic countries, such as the UK, Germany, France, Australia, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden, all the big donors, you need to really tell them, ‘We need more technical assistance to work on things like the effect of China on democracy’,” he concluded.