*Venezuelan analyst says that the presence of the People’s Republic of China exacerbated problems such as human rights violations and corruption in Venezuela and the rest of Latin America.

**The Asian Giant hides from the international media the fact that its investment in Venezuela was a resounding failure.

Expediente Público

With Hugo Chávez’s rise to power in 1999, the South American country was handed over to the People’s Republic of China, which provided massive financing to the Chávez regime and locked in a series of corrupt practices that it later replicated throughout the continent, with catastrophic results.

This is how Parsifal D’Sola, director of the Andrés Bello Foundation, summarized it at a Washington DC forum on Chinese influence and interests in the world, promoted by the International Republican Institute’s Center for Global Impact.

D’Sola is an analyst of Chinese foreign policy specializing in Sino–Latin American relations, with a focus on Venezuela.

“Since Hugo Chávez came to power, Venezuela’s institutional framework has gradually been eroded from within, and the arrival of China and massive financing in the late 2000s, at a time when oil prices were dropping significantly, facilitated and strengthened the co-optation of power in Venezuela,” stated D’Sola in an interview with Expediente Público.

Moreover, many of these corrupt practices that originated in Venezuela were later exported to the rest of the Latin American region, he added.

For this analyst, “Venezuela surrendered. It was a state policy of opening the doors to China and basically giving that country carte blanche to operate in Venezuela.”

The Chinese presence and the massive financing that it brought along with it generated an atmosphere of corruption in the Venezuelan leadership, initially led by Hugo Chávez and later by Nicolás Maduro.

“We are talking about the boom that took place during the 2000s and early 2010s, reaching a peak around 2013 when there was this change in the Venezuelan power leadership, when everyone began to see it, all these cases of corruption in connection with the Sino–Venezuelan fund coming to the surface,” D’Sola said.

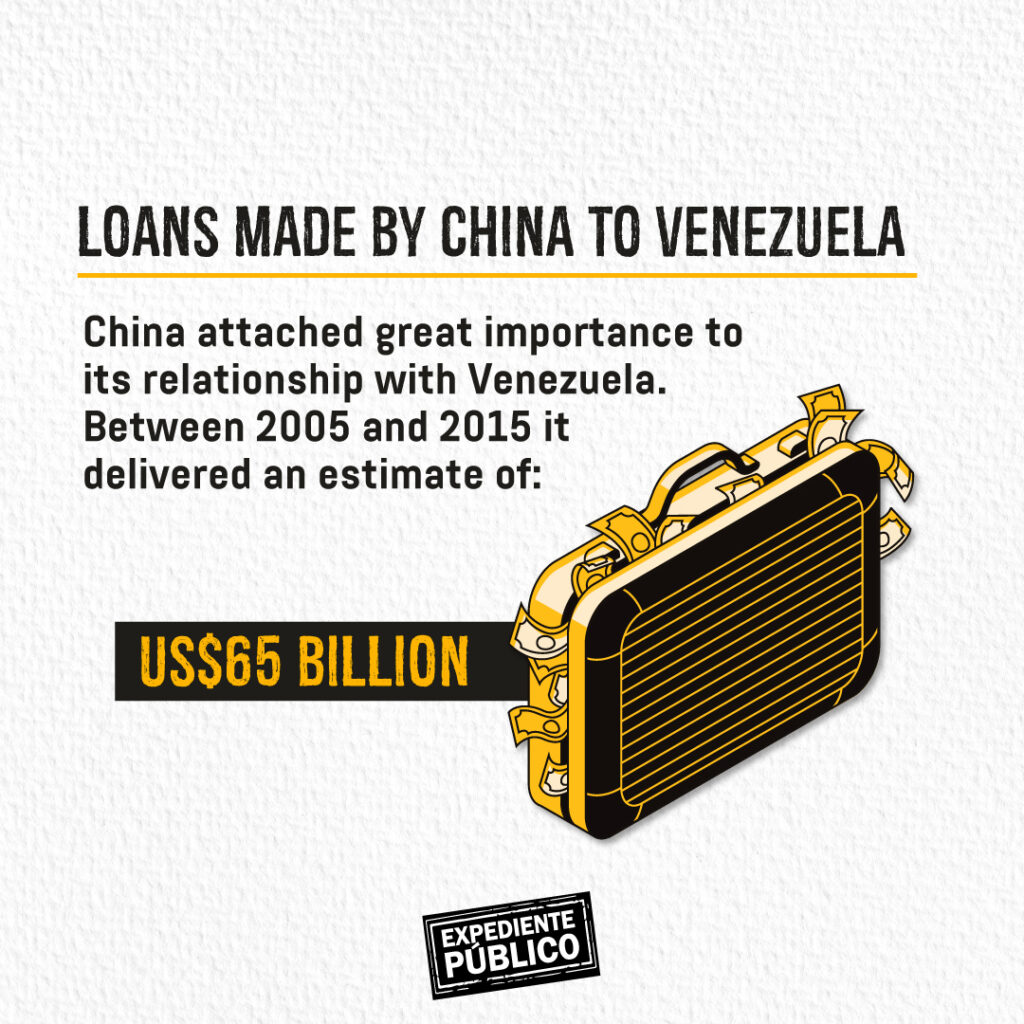

He recalled that over a period of approximately ten years, Venezuela received more than half of all the Chinese financing that was directed to Latin America.

“We are talking about around 65 billion dollars, when from 2005 to 2015, the entire region, from Mexico to Patagonia, received around 130 billion dollars. So this speaks of the great importance that China gave to Venezuela, and the results were catastrophic,” D’Sola said.

According D’Sola, China was unable to demonstrate any benefits of this financing to the rest of the region because there were no tangibly successful projects in Venezuela. This caused a certain rift between the two nations, to the extent that today the Venezuelan experiment is seen more “as a pebble in China’s shoe.”

“Venezuela disappeared from the front pages of Chinese state newspapers because it was a failure and they don’t want Venezuela’s failure” to be linked to them, explained D’Sola, who lived in the Chinese capital for eight years.

He added that an example of this failure is the “great migration” that has even affected the stability of the region. China wants to stay as far away as possible “from the abyss into which Venezuela fell.”

Lack of transparency

For D’Sola, “the relationship between China and Venezuela has been extremely damaging to the institutions” of his country. He acknowledged that the incursion by Chinese companies and government are not the main cause of the problems Venezuela has experienced in recent decades; however, they have “exacerbated” them due to the policies that were implemented.

According to him, China’s presence heightens existing problems in the region, especially in those countries that are governed by authoritarian regimes.

D’Sola, who worked as an advisor on Chinese foreign policy for the interim government of Juan Guaidó in 2019, said that one of China’s serious problems in Latin America is that its projects and investments do not go through any control process, nor is there public participation in the contracts.

“These contracts do not go through the channels, either of congresses or parliaments. This weakens the institutions and exacerbates the problems that exist in the region,” D’Sola stressed.

What is more, China does not demand transparency in negotiations, which is “to the detriment of our institutions and our democracies,” he added.

He also warned that the region’s governments have issued very few statements about the problems caused by China. “Sometimes, reduced to very specific cases, they bet on not antagonizing certain Chinese economic sectors or the Chinese government because that would affect development and many local industries.”

Diverse interests

According to D’Sola, who is also an analyst at the Chinese Latin American Research Center based in Bogota, Colombia, Chinese interests in Latin America are very diverse.

“In such a diverse region, Chinese positioning and interests in large countries like Mexico and Brazil are quite different from the interests China may have in small countries in the Caribbean or Central America,” he explains.

He refers to one of China’s main interests, if it could be described as a “macro trend;” namely, to receive support in international forums or multilateral organizations in order to promote policies that benefit its position in these institutions, but also in the international order.

D’Sola highlights China’s geopolitical interests in the region, which are supported by countries such as Venezuela and Cuba. Beyond their ideological affinity, the fundamental interest in these countries is that they could become mouthpieces for Chinese interests at the Latin American level. “These are main themes of many of China’s public narratives or diplomacies in the region,” he said.

D’Sola explained that just as there are interests in large markets such as Mexico and Brazil, there is also interest in a region that is very rich in mineral resources.

“China is always looking not only for new sources, but also to diversify so that it does not have to depend on only a small group of countries,” he said.

According to D’Sola, the Chinese state facilitates financing and support policies at the local level through its embassies. This implies expansion of and access to these markets for both state-owned and private Chinese companies.

False perceptions

D’Sola stressed that in Latin American countries “there is a false equivalence at the level of political elites” that equates the United States and China as being two similar dominant economic powers.

“Factors such as human rights; such as democracy, dictatorship, authoritarianism, are not part of the conversation,” said D’Sola.

This gives rise to a problem in the medium and long term, given the economic ties of dependency that have been established over the last two decades.

A Chinese company is treated as an international company, the same as a North American or a European company. Under this historical perspective, they are considered powers that come to the Latin American region to create relationships of dependency, to exploit, to damage the environment.

The Chinese are seen as no more than “today’s actors; yesterday it was the Americans, the day before it was the Europeans.”