*The political scientist Armando Chaguaceda warns that Russia has broadened its sphere of influence in Latin America to rival that of the now defunct Soviet Union.

**Russia’s influence ranges from its economic pull in countries like Brazil to geopolitical alliances with countries like Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, Russia’s chess pieces.

***Partnerships with Russia include teaching-learning processes on the repression of citizens’ freedoms and rights.

Expediente Público

Russian influence in Latin America now rivals that of the Soviet Union, ranging from military and economic pull to strategic security strategies and geopolitical alliances with authoritarian regimes. The Cuban political scientist, Armando Chaguaceda describes Russia’s influence in the region in an interview with Expediente Público.

“Its influence takes on various forms, impacting the economy through large quantities of Russian exports of automobile and aircraft parts,” along with primary materials and fertilizers to Latin America, particularly Brazil.

Russia also plays an important role in security issues and politics, exporting arms and military helicopters with a general disregard for the ideology of the government on the receiving end of these transactions. The country exports not only these materials but also mechanisms to repress civilians, Chaguaceda says.

Arms and repression

Chaguaceda explains that Russia has sold arms to Venezuela and invested in its energy.

Since 2005, Venezuela has purchased 53 helicopters from Russia.

Chaguaceda points to the case of Nicaragua, which “makes important but small investments in its military apparatus and cooperation to support the police.” Nicaragua has 11 Russian helicopters that it acquired during the era of the Soviet Union and the first government of the Sandinista regime.

Read: Departamento de Estado vigila presencia rusa en Nicaragua

Additionally, the Russians have established a satellite base, satellite tracking, and GLONASS, a Russian satellite navigation system in Nicaragua.

“With Cuba, there is less military support. Generally, the country does not purchase arms but rather, modernizes its own military capabilities. However, Russia does provide military technology and security to Cuba,” Chaguaceda warns.

Infodefensa.com confirms this idea, reporting that since 2016, Cubans have begun plans for a project led by Helicopters of Russia, together with the Cuban-owned Tekhnoimport, to create a maintenance company to repair Russian helicopters on the island. Cuba has 60 helicopters that it acquired from the Soviet Union.

Russia differentiates its relationships in Latin America by economic potential to acquire or refurbish arms, which puts Venezuela at the top of its list of regional alliances, followed by Nicaragua and lastly, Cuba. But not all self-proclaimed “socialist” countries buy arms from Russia. Some countries, such as Mexico and Colombia, buy them from the United States. The Mexican Naval Ministry bought the first Russian helicopters in 1994. Later, the Navy and the Air Force acquired 73 helicopters, according to data from the Defense Ministry of Mexico. In Colombia, according to the state export company of Russian arms, Rosoboronexport, there are 50 Russian helicopters, half of which are used by the military; the other half are for civilian use.

Read: Comando Sur advierte amenazas de Rusia y China en Centroamérica y el Caribe

But these connections with undemocratic regimes in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua go beyond arms sales. “Cooperation exists on security and, most likely, personnel training. In other words, justice sector personnel in these countries have received training in Russia,” explains the academic, Chaguaceda, who also warns of Russia’s active cooperation with these regimes to repress civic spaces and freedoms. “There are extraordinary similarities between Russia and these countries with regard to the laws or ways in which the government treats the opposition, which restrict the free exercise of the press, protests and manifestations,” he underscores.

“Symbolic reciprocity” or the backyard theory

Chaguaceda looks at the thesis of the Russian academic, Vladimir Rouvinsky, author of the recently published book, Rethinking Post-Cold War Russian-Latin American Relations, which sustains that since the 1990s, Russia has wanted to recuperate its economic and commercial power. However, since the 2000s, the country has contributed to a multi-polar world.

Rouvinsky calls this thesis “symbolic reciprocity.” “In other words, Russia tries to maintain influence in the United States’ backyard,” just as the United States influences Russia’s backyard.

This type of influence depends on involvement in different areas, particularly related to recuperating and broadening Russia’s presence in Latin America, which is superior to that of the Soviet Union in its era of influence because of Russia’s strategy to reach beyond ideological similarities while incorporating political components.

“Understanding influence from the perspective of viewing Latin America as the United States’ backyard, Russia’s goal is to get even with the United States for what it has done and continues to do in the post-Soviet space, explains the Cuban academic.

Furthermore, Russia has political and cultural influence in the region through the Russian media, Sputnik and Russia Today, “which have become important sources of information for Latin American audiences,” says Chaguaceda, who is one of the most notable Latin American academics on the study of democratization and democratic backsliding in Latin America and Russia.

Until Russia declared war on Ukraine, Russia Today and Sputnik had achieved a great deal, spreading news to audiences at a relatively low cost and in six different languages. However, after the start of the war, the Russian media’s reach dwindled due to sanctions implemented by dozens of countries on pro-Russian propaganda.

Authoritarian similarities

Chaguaceda explains that Russia has ideological similarities with certain sectors in Latin America, affecting governments, society, and public opinion. This connection can no longer be seen through the old Cold War logic of communism versus capitalism, as the world has adopted a capitalistic economy. Rather, there are two different ways of understanding the sociopolitical world order.

Read: Estados Unidos: la invasion rusa y la Venezuela de Maduro

In other words, these ideological “differences exist between democracy and autocracy, as autocracies provide alternative forms of undestanding political regimes and illiberal ideologies.”

Chaguaceda explains that liberal values, such as the division of powers (executive, legislative, and judicial), open society, multiculturalism and diversity, market regulation, and institutions that serve citizens, are rejected by the extreme left and right, political sectors that align with a sociopolitical order similar to that of Russia. Russia, as a conservative, autocratic regime with a revisionist and illiberal vision, atracts groups and governments of both political extremes in Latin America.

One of the representatives of the far right is Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, a political personality who shares similarities with Vladimir Putin. In Europe, a similar phenomenon occurs with the xenophobic tendencies of the far right.

These similarities in governments throughout the world are based on both explicit cooperation and lessons learned on autocracies. Another key factor is also the «support and endorsement of Russia’s foreign policy and the policies of these countries in mutual declarations.»

“In the recent case of the Russian war on Ukraine, a strategy of calculated ambiguity exists, in which Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela,” neighbors of a major world power, “neither voted completely against the Western consensus and a large part of the world nor that the war was injust.” Each of these countries would be “shooting itself in the foot by saying that a world power could invade a small country,” Chaguaceda explains.

“They cannot vote in complete support of Russia, so they vote in an ambiguous manner to oppose those who condemn the war in Ukraine. This calculated ambiguity perfectly describes these governments’ afinities with Russia,” Chaguaceda emphasizes.

The case of Brazil

Russia cultivates many different types of relationships in Latin America. Even after the Cold War, Russia has the greatest amount of diplomatic support that it has ever had in the region,” according to Chaguaceda.

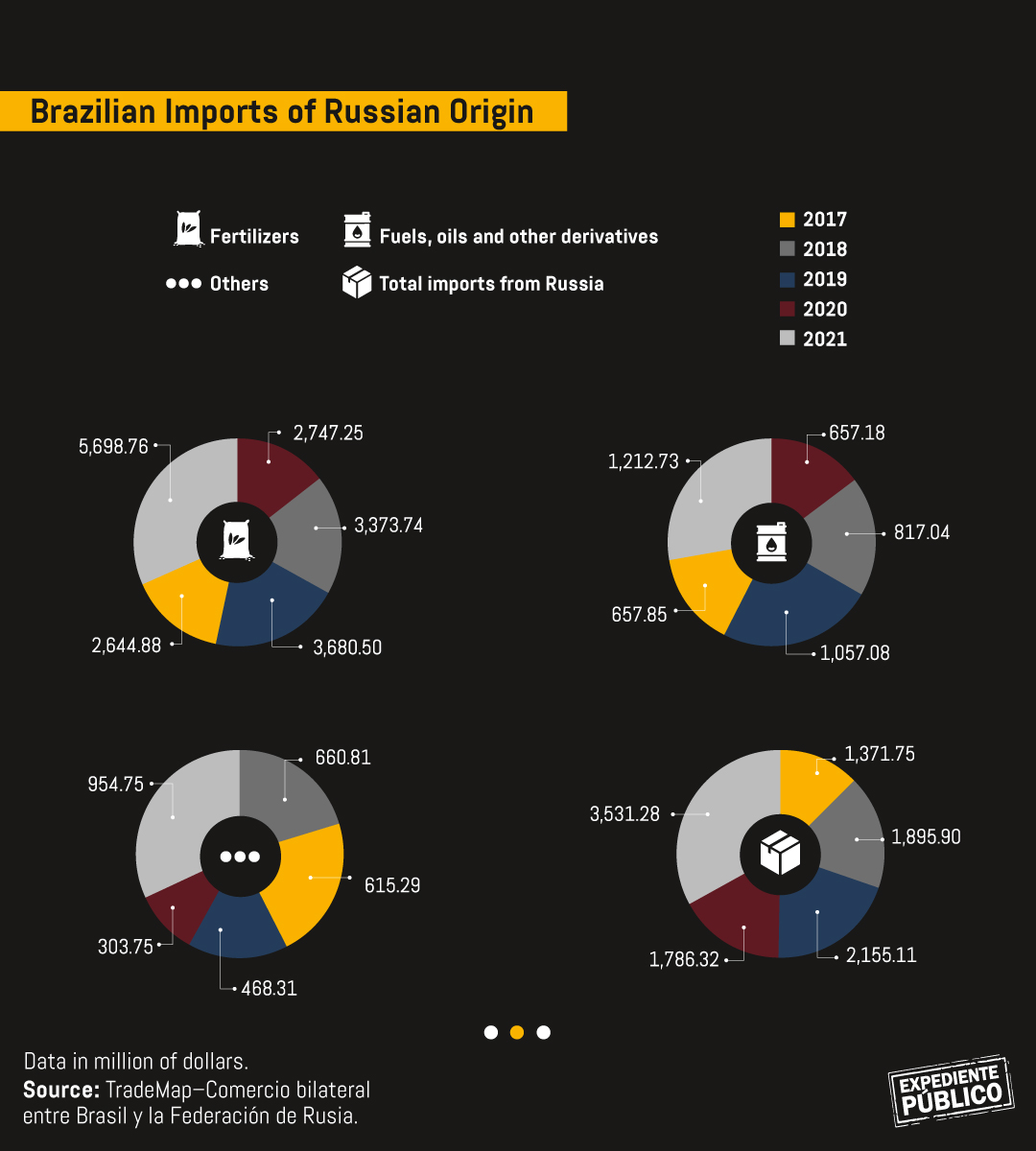

Economically, Russia’s main partner in the region is Brazil, which received more than US$5,261 million from Russia (1.1% of Russia’s total exports) in 2021.

Russia is also one of the South American giant’s main sources of fertilizer for its agricultural industry, where prices of inputs have risen following the pandemic and because of the war in Ukraine. This situation has incentivized Brazil not to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.