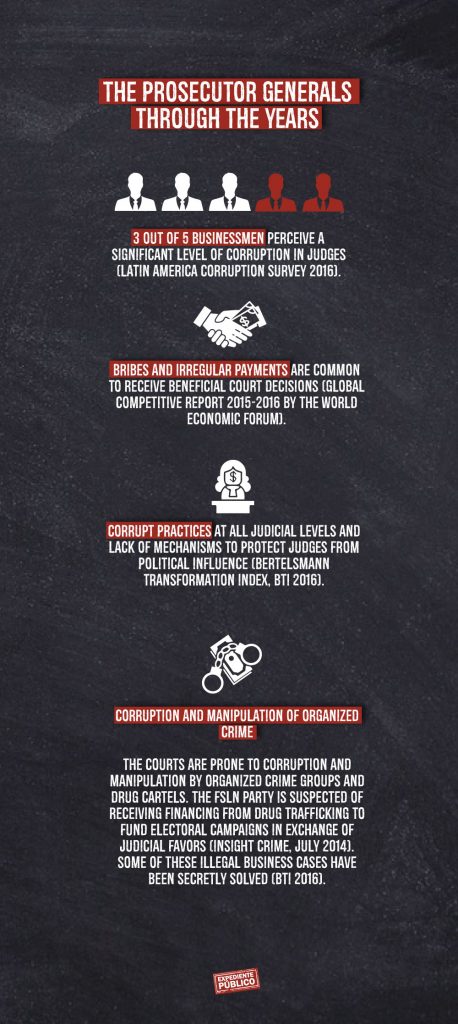

Various magistrates and judges in Nicaragua have been accused of being at the service of Daniel Ortega and the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) power apparatus, which has governed since 2007. However, the Supreme Court’s lack of independence is just one scandal added to a long list of instances of nepotism, bribery, extortions, and even drug trafficking tied to the judiciary branch in this country.

Various magistrates and judges in Nicaragua have been accused of being at the service of Daniel Ortega and the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) power apparatus, which has governed since 2007. However, the Supreme Court’s lack of independence is just one scandal added to a long list of instances of nepotism, bribery, extortions, and even drug trafficking tied to the judiciary branch.

Proof of how the judiciary branch has completely folded to the Ortega regime begins with the April 2018 social protests. These uprisings resulted in hundreds of trials that lacked legality or draconian evidence, in addition to wrongful convictions in Managua courts with a preexisting history of corruption and sentencing manipulation.

Throughout the legal system, the FSLN has positioned key loyal persons with a non-literary level of military discipline, such as Adela Cardoza Bravo, former member of the Armed Forces and head of the Second Criminal District Court, or Juana Méndez, former agent of the Ministry of the Interior in the eighties, current magistrate, and former judge that condemned former President Arnold Alemán for corruption.

Furthermore, until January of 2019, Rafael Solís, godfather of Ortega and Rosario Murillo and founder of the Sandinista People’s Army (EPS), exercised de facto power in the CSJ, and Lenín Cerna, former Chief of State Security someone very close to the president, acted as the legal-political officer of the apparatus.

THE CAPTURE OF THE JUDICIARY

Despite losing power in 1990, Sandinismo prepared to «govern from below» and achieved strategic positioning within the judiciary system. In those years, the liberals dismissed minor judicial positions in order to hold high-ranking posts. As the political party in power, liberals thought that decisions were only made from the top of the legal system, recalls a former prosecutor who, for security reasons, prefers to omit his name.

In reality, control over the judiciary system does not only depend on the magistrates, rather it descends to the appellate, district, and local courts. In this context, the judicial syndicate affiliated with the National Worker’s Front (FNT) maintains pressure on the entire system, invading it with administrative party personnel and monitoring it through municipal and department FSLN political officers.

When Arnoldo Alemán, representing the Constitutionalist Liberal Party (PLC), assumed the presidency in 1997, the Supreme Court had eight non-Sandinista and four Sandinista magistrates. However, only one magistrate represented the PLC: Guillermo Vargas Sandino.

Therefore, part of the 1998 pact between Alemán and Ortega existed to divide the cake that was the CSJ. First, Alemán and Ortega created four new positions. As the magistrates’ terms ended, there ended up being eight positions for each party. From that division, the Sandinistas worked to obtain the majority, monopolizing the appellate and lower courts, as well as the administrative personnel.

José Pallais, former President of the Commission of Judicial Affairs of the National Assembly and one of the most visible leaders within the democratic opposition, cautions that the FSLN maintained a systematic recruitment of opponents within the judicial system for a long time, offering protection and stability, which is why many CSJ liberal officials began to desert the PLC to maintain their positions now subordinate to the FSLN.

After the pact between Alemán and Ortega, officials at different levels were co-opted from their 50% representation, and the Sandinistas expanded their influence through partisan inclusion. Currently, having reached a 90% majority, the judiciary is composed of FSLN cadres with commissioners that resolve trials based on political decisions, sustains Pallais.

A crucial moment for the capture of the judicial branch was the 2003 corruption charge against Alemán, where the case was referred to the Sandinista Judge Juana Méndez. Daniel Ortega already had key positions occupied and took advantage of liberal weakness to extract favors from officials, including the Parliament presidency, despite not having a majority. The PLC conceded its power to save the caudillo, in such a way that by the time the 2006 elections came around and were lost, political representation held by Arnold Alemán within the judiciary system had diminished.

With the constitutional reform of 2014, the FSLN made a new ally with whom it would make a pact: the so-called public-private alliance which allows Nicaraguan capital to interact with the State. The alliance even gives some positions in the CSJ to the business community. This is how Virgilio Gurdián Castellón, José Adán Guerra, and Carlos Aguerri Hurtado appear as magistrates, as a gesture of good will to the business community.

Alberto Novoa, former Prosecutor General (2004-2007) during the government of Enrique Bolaños, points out that this is the renewal of an old pact, which does not involve liberals, but rather the business bourgeoisie.

This representation given to the business community makes it clear that whoever seeks to oppose Sandinista economic interests in the legal field will lose.

In essence, through the judiciary branch, there exists an apparatus that controls society and protects FSLN capital, says the former prosecutor.

THE LOYALTY SYSTEM

The sanctions, promotions, transfers, and dismissals of judges are decisions centralized within the National Council of Administration and Legal Careers of the CSJ, which consists of four magistrates that do not form any chamber, but, rather, work for the administration of the system.

The Council is composed of CSJ President Alba Luz Ramos Vanegas, who has at least seven of her family members, including her daughter, working in the judicial branch.

Former Prosecutor Alberto Novoa explains that the Sandinistas must pass loyalty tests in order to access the most important positions. These loyalty tests are a series of formal and informal mechanisms that measure the candidates’ fidelity to the political party.

In the guild of judges chosen for relevant cases lies Ernesto Rodriguez Mejía, the judge who convicted Brandon Lovo and Glen Slate for the murder of reporter Ángel Gahona while she covered the 2018 protests in the Caribbean city of Bluefields. Rodriguez was later promoted to Magistrate of the First Chamber of the Civil Court of Appeals in Managua.

One month before the start of the sociopolitical crisis, Rodríguez covered up that the Armed Forces had assassinated a Cameroon migrant at the southern border. In March of 2018, this same judge condemned the mother of the victim from Cameroon for human trafficking. The mother had demanded the body from Forensic Medicine and denounced the military.

Another judge loyal to the apparatus of repression is Julio César Arias Roque, who condemned various dissenters who rose up against the Ortega-Murillo regime beginning in April 2018.

Arias was a labor unionist, labor and criminal lawyer, and public defender. As judge, he maintained the leader of the Opposition, former foreign minister, congressman, and banker, Eduardo Montealegre, on the verge of being arrested for two years for his involvement in a corruption case that began in 2008 and was connected to government bonds. Four years earlier, the same Judge Arias had prosecuted an electoral magistrate of the Liberals for his ties to drug trafficking. However, Arias is most remembered for releasing the brother of world champion boxer, Román Gonzáles, arrested in 2014 for selling cocaine.

Edgard Altamirano López is known for his excessive sentences dished out to relevant opposition leaders. Pedro Mena and Medardo Mairena received more than two centuries of prison and Luis Pineda Icabalceta received 159 years. Altamirano also took up the case of journalists Miguel Mora and Lucía Pineda, the case of Eastern market merchant, Irlanda Jerez, and the case of Masaya protest leaders Adilia Peralta, and Cristian and Santiago Fajardo. Moreover, Cristian Mendoza, alias «Viper», a former protester that participated in the sit-ins and barricading of the Polytechnic University of Nicaragua (UPOLI) and was subsequently adjudicated by Altamirano, clarified after being released from prison in mid-June 2019 that paramilitaries forced Mendoza to incriminate himself and testify against members of the Opposition.

Melvin Vargas García, Judge of the Seventh Criminal Court District, was a diligent operator of the Ortega regime’s system of repression in 2018, sentencing dozens of political opponents.

Abelardo Antonio Alvir Ramos, nephew of Alba Luz Ramos, took up the case of a paramilitary that killed Brazilian student Rayneia Lima, sentencing him to fifteen years, albeit his being liberated in 2019 because of a controversial amnesty law.

On the other hand, judges who opposed this apparatus or limited actions taken against the Opposition faced dismissal. Indian Gallardo, Judge of the Ninth Criminal Court District of Managua, was dismissed for permitting the courtroom presence of the families of three Matagalpa protesters and summoning the National Penitentiary System for having removed two political prisoners from the courtroom without their consent. In the city of Bluefields, Carmen del Socorro Merlo Narváez, Criminal Court District Judge and grandmother of political prisoner Brandon Lovo, and Edgard Henríquez, Criminal Hearing District Judge, were removed.

DRUG TRAFFICKING AND THE SUPREME COURT

In Nicaragua, there are few possibilities that corruption allegations against judicial officials are investigated or prosecuted. Corruption charges against public officials are rare, according to Freedom House’s 2019 Freedom in the World Report.

«[This is] because the justice system and other public bodies are generally subservient to Ortega and the FSLN,» determines the Report.

Scandals within the judiciary branch are extensive and even involve magistrates of the Supreme Court (CSJ), such as the 2005 implication of Sandinista Magistrate Róger Camilo Argüello in the theft of $600,000 dollars from a judiciary account seized from Colombian drug trafficker Luis González Largo and the 2018 arrest of the son of Sandinista Supreme Court Magistrate Francisco Rosales Argüello, David Salomón Rosales, detected by Interpol to have been eating at a restaurant in Costa Rica with Juan Pereira Ramos, wanted in the United States for drug trafficking. Although Rosales was released in less than 24 hours, the connection gives rise to all kinds of speculations.

The Sandinista Magistrate Marvin Aguilar García is also tainted. His nephew, José Antonio García Aguilar was caught red-handed while in possession of a shipment of cocaine at the southern border in 2014 and sentenced to prison for organized crime, international drug transportation, and the possession and use of restricted weapons. Seven other men were prosecuted with him.

García only received house arrest in 2015 and, once again, became testament to favoritism within the legal branch of government with his release from prison in 2011 due to an alleged error in the legal process of his being prosecuted for forming part of a network of theft and illegal trafficking of vehicles.

José Pallais, jurist and former President of the Commission of Judicial Affairs of the National Assembly, sustains that these scandals would cause dismissals, renouncements, or investigations in other countries, but that in Nicaragua «this is avoided with the shield of protection of the presidential couple (Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo): «if you are loyal, you are guaranteed protection, (this being) something that operates at all levels.»

According to former Prosecutor General of the Republic from 2004 to 2007 Alberto Novoa, «scandals in Nicaragua are major because they involve key national figures, (which is why) something small implicating a magistrate (of the CSJ) or Appeals does not invoke havoc.»

Former Magistrate Rafael Solís, having made public his letter of resignation in January of 2019, points out that Nicaragua is living «a dictatorship with characteristics of an absolute monarchy of two royals that have eradicated the all-independent powers of the State, leaving the same judicial brunch, to which I belong, reduced to its most minute expression.»

THE NEED FOR REFORM

Katya Salazar, Executive Director of the Due Process Foundation (DPLF) located in Washington D.C. has affirmed in statements made to Expediente Público that institutions in Nicaragua began to deteriorate in the last decade and no one did anything about it.

Salazar explained that little could be done in a situation like that of Nicaragua and that the Alemán-Ortega pact had reduced the ability to influence and change the rules of the game. Salazar continues that «this is not because [similar situations] do not exist in the rest of Central America. They do; however, they occur through partial co-optation. Nicaragua experiences co-optation at a different level» that has followed in the steps of Venezuela, with the difference being that it fell below the radar for years and no one paid attention.

Although there are a series of minimum standards that guarantee the independence of the judiciary branch, these are not possible with Ortega in power. This is because of the Alemán-Ortega pact and co-optation. Salazar summarizes that «the most relevant standards that have to do with the situation in Nicaragua are those that regulate the selection of high-ranking judiciary officials; this has been deteriorating for years.»

As to whether or not the judiciary branch can regain its independence, DPLF sees such an advancement as unlikely without a change of power, considering that important and necessary forms should be made «starting with the intentional cleansing of the organisms of justice. However, this cannot occur until there is a change in administration.»